5.17.24 — A Mind of Its Own

Once artists had workshops, with young assistants to grind pigments, to prepare a painting’s ground, and at times to paint. Now they may have only a studio and a computer. They may work out their thoughts on it, in virtual sketch pads. They may even call the results art.

Harold Cohen does, but he leaves the software to carry out the details, with plotters as its pen and acrylic for color. It gives him a dual canvas for his own art, in software and, ultimately, on the wall—and I work this together with recent reports on the new media of an artist’s lifetime as a longer review and my latest upload.

Cohen, then close to forty, got the idea at the University of California, San Diego back in the 1960s, and he set out to make it real. By the 1970s it had its own exhibition and a name, AARON (like, I presume, AI-ron). It has new relevance today, when people cannot talk often enough about their fears and hopes for AI. It also has a retrospective at the Whitney, through May 19, but what exactly is it? Is it an assistant, a collaborator, a competitor, an alter ego, a friend, or simply a medium? Could it have, like an assertive child, a mind of its own?

You may have heard this story before—and not just online. When Leonardo da Vinci painted an angel for Andrea del Verrocchio in 1475, the master, it is said, was so awed that he never painted again. To less romantic scholars, it was merely what would have been impossible before the Renaissance and medieval money, a business decision. Verrocchio had a demand to meet for both painting and sculpture, so why not specialize? It is only fitting that AI most often makes the business section of The New York Times today. But could the label conceivably apply to Cohen starting fifty years ago?

Regardless, his show makes a flashy first impression. It devotes an entire wall for what could equally well be video art or a painting’s coming to be. At any given moment, it is a work in progress, and Cohen considers his task an examination of an artist’s cognitive processes. Others might put software on a diet of Web sites, with every new work filling in the blanks. That could leave instructions to such generalities as a painting about X in the style of Y. The British-born artist would rather take things step by step.

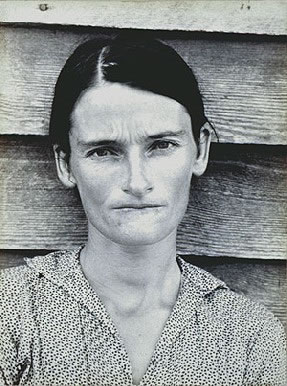

That big mural really moves. If AARON does have a mind of its own, it thinks fast. It lays out one shape after another and on top of another, for an increasingly dense landscape of truly wild flowers, before starting again. Color fills the black outlines as quickly as they appear. When it comes to actual canvas, too, Cohen’s strength lies in those layers. Subjects include still life and figures akin to portraits, with a woman behind a flower pot, for a compressed space within a deeper world.

Modernism was always about space and its perception, and his early work picks up on Paul Cézanne and his bathers. It sets bathers within that denser, wilder landscape. AARON may not realize them as individuals, and what look portraits might be studies in the very idea of introspection. Eyes cast downward, and a hand raised to lips might hold a cigarette or serve as a shield. Cohen, in turn, gains over time from a return to basics in the software itself. Sketches reduce figures to jointed lines, like machines.

Their style may look more appropriate for advertising or nursery school than for art, much as I enjoyed that video mural. Even there, software has it limits, although human art can be formulaic enough, too. If AI from Refik Anadol amounts to visual elevator music, its successor in MoMA’s lobby, by Leslie Thornton, has its own soothing swirls. For all the hype, does any of this add up to intelligence? Stendahl quipped that God’s only excuse is that he does not exist, and one might say the same of AI.

Their style may look more appropriate for advertising or nursery school than for art, much as I enjoyed that video mural. Even there, software has it limits, although human art can be formulaic enough, too. If AI from Refik Anadol amounts to visual elevator music, its successor in MoMA’s lobby, by Leslie Thornton, has its own soothing swirls. For all the hype, does any of this add up to intelligence? Stendahl quipped that God’s only excuse is that he does not exist, and one might say the same of AI.

For all that, AARON’s landscapes have an appealing density, figures and still life an appealing simplicity. Cohen’s premise is more interesting still. The Whitney considers the canvases the art and the video a look behind the scenes to their creation, and it gives equal weight to both. It has only a handful of paintings, from the museum collection, the video, and two plotters that Cohen designed himself. There have to be two, because software can turn out any number of multiples from the same instructions, as theme and variations. One might call think of AI as more an aspiration than a fact, but one can always hope.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.