Paint Fast and Die Young

John Haberin New York City

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat comes with a lot of baggage for such a short stay on planet Earth. His retrospective evokes everything from Matisse and Minimalism to African myth and Afro-American history. It calls him the last modernist, "perhaps the last major painter of the twentieth century." In his visual traces of Abstract Expressionism and his text echoing Jim Crow and Charlie Parker, the Brooklyn Museum senses the weight of history.

Forget all that. Until his death in 1988, perhaps no other painter lived so determinedly in the present. It can make his work painfully glib or stunningly immediate. It makes him a vital and treacherous model for artists even today.

Stardom and sanctimony

Jean-Michel Basquiat understood about baggage. A native New Yorker in the transient East Village scene, he knew his way around. A child of Brooklyn's black middle class, he felt the benefits of education, the burdens of success, the limits of American tolerance, and the pressure to play the outlaw. The darling of collectors before burning out at age twenty-seven, he still serves as a poster child for debates about the roots of underachievement. He could almost resemble the hero's best friend and childhood protector in The Fortress of Solitude, only Jonathan Lethem's Mingus winds up in prison rather than dead of an overdose.

Everyone had something to project onto him. The media found a hip, downtown artist living on the edge. Conservatives found their faux naïf living off liberal guilt, and an emerging dealer, Anina Nosei, found a superstar. In his first film, Julian Schnabel found the contradictions of his own circle. When his Basquiat meets Andy Warhol in Warhol's last decade, one hardly knows whom to call the fool. Surely Andy Warhol himself did not.

Basquiat happily projected things onto himself. Surely the fastest and most ego-driven artist even in the wake of Neo-Expressionism, he managed his career like clockwork. Starting with graffiti, signed only SAMO, he cultivated a reputation—and an air of mystery—without actually having to tag trains. With a handle that meant "same old," he played the instinctual genius while letting on he knew better. He partied at the Mudd Club, dated Madonna long before she made art, and exhibited in the 1980 Times Square Show and P.S. 1's "New York/New Wave" exhibition, which together launched art beyond Soho. Leave it to others to decide which mattered most.

The Brooklyn Museum does not like a career of contradictions, much less of superficiality. It will not even settle for an influence on street artists of today, such as Barry McGee and SWOON, or its smart simulation from Raymond Saunders. It wants to rescue Basquiat from his moment on the art world's merry-go-round. It projects an artist aware of himself and of all time.

The retrospective comes bathed in sanctimony. Its two floors cover barely half a decade, those brief years after Club 57 in the East Village, but they halt a dozen times for elaborate wall text—including (seriously) a testimonial from Basquiat's second-grade teacher. In deference to his Haitian father and Puerto Rican–American mother, the text comes in three languages. Every other month seems to signal a new stage in a formidable career, with still further mastery of form, media, and cultural allusions. When it reaches his death, the curators cannot help adding "accidental." Clearly no one of such noble stature and sweet disposition could have toyed with self-destruction.

The selection, too, announces greatness. It downplays the bulk of his output, those quick outlines surrounded by bold words and fields of white. It prefers Basquiat's larger paintings, with broad expanses of color and stronger ties to painterly tradition, and the denser concatenations of words of his last years. Nor am I altogether complaining. The most colorful paintings show him at his best, with his darkest and most intense images of blackness. Their detail anticipates trends today, including the influence of cartoons and outsider art.

Center stage

The saga of a sanctimonious hipster should get one thinking, though. It responds to charges of facility with facile words. To one side lie innocence, nature, and immediacy. To the other lie experience, culture, and awareness. True, a sweet second-grader can aspire to greatness, but that forms part of the myth, too.

As its most lasting legacy, Basquiat's decade exploded the myth. It did so by its failures, including the loss of so many lives. As perhaps his most moving work, Basquiat created a memorial to Andy Warhol. Its hinged doors suggest a tombstone. Its simple signs evoke Warhol's appropriations—and Basquiat's own as well. It shows an artist aware of what his career owed to another, but also of his own increasing risks and diminishing output. Then again, what would one think of Jackson Pollock if he had died as young?

The decade did so by its success, too. If Basquiat became an overnight sensation, he laid the groundwork for the higher stakes and greater accessibility of art now, in which the image of the artist is all image. Most of all, the decade did it by changing the terms of success. With East Village art, the avant-garde captured the mainstream, and performance art became art as performance. Basquiat achieved success by recreating his own outsider image. He has no need to reach for eternity because he never leaves the stage. The self of Neo-Expressionism has itself become a proliferation of signs.

At the center of almost every painting, he places the same old black male, reveling in his fortress of solitude. Women hardly appear, even as objects of desire. Apart from a spin on Manet's Olympia, on its way to New York for "Manet / Degas," with its often-forgotten black servant, I caught only the scrawled word mujer, empty of referent. Besides, the shift in focus from Olympia to her maid renders invisible what Edouard Manet or Wardell Milan thrusts in one's face, a woman of leisure daring to look back. Paint largely obliterates both figures anyway. Basquiat and his desires have moved on.

All of black history channels through that central figure. Basquiat admired jazz, especially bebop. Yet he treats music not as ancestry, an other to the hero, but as his environment. I imagine it playing in his studio as he worked. A large, circular black painting, with an irregular white interior circle, puns on the only two physical objects he knows for sure—paint and vinyl. In ensuing years, he refers to African spirits, but as gods and tricksters that he can assimilate to his portrait of the artist.

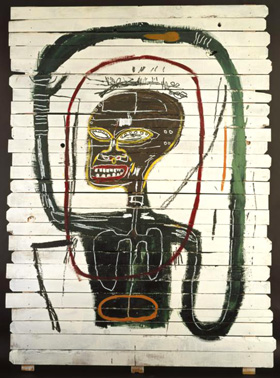

Basquiat's avatar takes on many roles—elusive, deceptive, pained, ironic, humorless, dismembered, and whole, but always angry and proud. Near the start of the show comes an enormous head, its slashing black outlines heightened by primary color, especially deep red. By the end, the man has dwindled to multiple, tiny stick figures, like an East Village toll of early death. In between come artists, warriors, and kings, with the traces of a studio, a sword, or a crown. They suffer, and they cry out, but Basquiat never openly plays victim, never leaves the stage, and never, ever escapes the present.

Here and now

Everything seems to exist in the here and now, starting with the act of composition. Much of the retrospective dates from barely eighteen months, by an artist barely of drinking age. In 1982 he turned out more than a work every other day, sometimes up to fifteen feet long. Not surprisingly, he sticks to quick-drying media—the big smears of acrylic, the words in black paint stick, a dash of spray paint. Who has time to wait for tomorrow?

Between his parentage and the streets of New York City, he must have heard plenty of stories, but he does not retell them in images. The hero faces down a heritage of oppression, but as words, often repeated over and over on a single canvas. Mississippi, obnoxious liberals, the irony of the black policeman—even the choice of enemies implies a focus on the recent past, not to mention an artist confident enough to stare down his supporters.

Of course, Basquiat saw plenty of stories as well, especially in modern art. And they, too, have a way of shifting into the present tense. Word painting derives from collage, and any combination of ego and facility recalls Pablo Picasso. However, Cubism dismantles vision, along with the distinction between painting and citation from the past. Basquiat imports words and images into a single field of paint.

A confrontation of word and male image also makes me think of Pollock before drips, as in the pretend arithmetic of Man and Woman. However, Pollock in his thirties was still seeking the Jungian unconscious. Basquiat is daring the conscious viewer to deal with the facts.

His performance was far too much a one-man show, but his present tense lives on. His reputation did fall for a while after his death, which may explain why the retrospective draws most often on private collections built, no doubt, in a headier climate. The show can afford to pick and choose where Basquiat would not, but far too much appears thoughtless and repetitive nonetheless. It does not, however, look irrelevant. The dead ends of a short life and a short-lived East Village scene have acquired new meanings.

The same black serves for text and drawing, like the mix of words and images so prevalent in painting now. The focus on "attitude" extends to photography now—and not only in the inner city. Women today portray themselves as conscious, proud, dangerous, or hurt. Cecily Brown or Chloe Piene could well be using Basquiat's scratchy line, fierce color, and assumption of a white, male audience. One can see him as the missing link between Cy Twombly's classical repose and a woman flat on her back. One can see him as the bridge between the eras of Jungian and drug therapy, with all the attendant gratifications and side effects.

Back to the present

As a bridge between eras myself, I returned only slowly to my personal present. I walked the entire way home.

It was not my first time on foot from the Brooklyn Museum to Manhattan, a chance to relax and let a show sink in. I had done it last after the Sargent portraits this past fall. I took a different route this time—not through such lovely connections as Park Slope, Carroll Gardens, and Brooklyn Heights, where Basquiat earned that teacher's approval. I did pass through the East Village, which helped him achieve fame. Yet I took the Williamsburg Bridge instead of the Brooklyn Bridge, passing first through Fort Greene and Clinton Hill, historic districts groping with poverty, gentrification, and the very possibility of a black middle class.

I wanted to catch a few Brooklyn and Lower East Side galleries further along. But I also wanted to meditate on the contradictions in any New Yorker's life—and certainly in his. New York and its people always comes alive in its streets, especially the streets that so often go unseen. People sometimes try to put their past behind or to exploit it to new ends, and sometimes the city leaves them behind. Basquiat reveled in images borrowed from those he most wished to forget.

The Brooklyn Museum wants it both ways, just like the artist. It wants a tribute to high seriousness, with the distortions in Basquiat's art that this entails. And, as with its remodeling and "Open House" last year, it wants a greater touch with the Brooklyn community. Sometimes it pulls off both at once, as with all that wall text in three languages, testifying to the artist's mixed heritage and the museum's accessibility. It works, too: visitors do not look like the Met's usual customers, and they are glad to be there.

I had gone in the first place because of a contradiction. The artist had always seemed inconsistent at best, shallow at worst, and wildly self-serving, with a distinctly male ego. Yet women artist I knew were dying to see the show. His voluble signs, both the text and the scrawled images, spoke to their self-representations now. Does Basquiat put his ego first and leave the words to the background? Perhaps, but sign systems and the unconscious always take on a life of their own.

Basquiat did not just live fast and died young. He worked as if knew time was running out. In a decade poised between the avant-garde and big installations for big markets, he helped give painting itself its fifteen minutes of fame. Does that simply add one more cultural icon to a young artist's long list of appropriations? Has he become a patron saint for art with a wider public than ever, along with Warhol, Keith Haring, and Frida Kahlo? No wonder his retrospective feels so much a part of the present.

The retrospective Jean-Michel Basquiat ran at The Brooklyn Museum through June 5, 2005. Related reviews look at the museum's 2011 cancellation of "Art in the Streets" and "Defacement," Basquiat's response to the death of Michael Stewart, also a subject for "Grief and Grievance."