Architecture at War

John Haberin New York City

Frank Lloyd Wright, Lebbeus Woods, and the City

What do you get if you ask someone who hates cities to plan for their future? The results might look nothing like a city. They might not even be built.

Then again, they might look all too much like architecture today. All apply to nearly forty-five years of projects and proposals in "Frank Lloyd Wright and the City." Yet perhaps their greatest impact was on the Museum of Modern Art itself. The same turmoil in the mission of a modern museum or modern architecture drove the experiments of Lebbeus Woods at the end of the century. Their utopias were violently at odds, with one architect wishing for rural light and peace, the other for war. Taken together, though, they stand at an equal distance from the needs of a city and its inhabitants.

Wright stuff, wrong city

Well, not solely the impact on this museum and this city, although MoMA celebrates a partnering with Columbia University to acquire the Frank Lloyd Wright archives, with additional displays sure to come. The architect's biggest tourist attraction is a museum, the Guggenheim, in America's most populous city at that. And his influence goes back to 1913, when he designed a building twenty-four stories high for a newspaper, the San Francisco Call. It was to link to one of San Francisco's first office towers by a shorter and more public arcade, much as Renzo Piano linked two older buildings in extending the Morgan Library in 2006. Saint Mark's in the East Village commissioned Wright in 1927 to design an apartment tower dwarfing the church and the neighborhood, simply to generate money. MoMA's expansion of 2004 anyone—or the one to come?

Not that their impact was altogether baleful. Learning from his mentor, Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright intended the Call building to have a load-bearing concrete exterior, leaving the interior free. It anticipates the Whitney's flexible spaces and movable walls on Madison Avenue, by Marcel Breuer, along with many a great museum since. Besides, nothing in the small show at MoMA made it past Wright's delicate plans and elevations except for a 1943 laboratory research tower for S. C. Johnson in Racine, Wisconsin, and headquarters in the mid-1950s for J. C. Price, a pipeline contractor in Oklahoma. The rest were just too visionary, like the expansion of the Saint Mark's project to three towers radiating out from the church and a comparable pinwheel three years later for Chicago. Modernism's Radiant City, here we come.

Nor was Wright's greatest impact (sorry or not) on museums, not by any means. Yes, lifting the Johnson chemistry lab above a courtyard looks forward to the wasted space, deferred function, and phony display of public access in atriums like MoMA's own. Yet the show's final and ultimate vision is not a museum but a mile-high tower meant for Chicago in 1956. It sounds rather like the global competition now to top the previous record for height, as well as the heavy-handed symbolism of 1776 feet in height rising at Ground Zero. But then Broadacre City, a dream child first displayed in 1935, was to grow horizontally instead, across the countryside, to bring "the citizen of the near future . . . the gift of his motorcar." The show's centerpiece, a tabletop Broadacre City almost filling a room, could serve as metaphor as well as model for suburban sprawl.

Did the architect's ambitions run every which way, up, down, and sideways? Control freaks and visionaries are like that, even with such architects as Ettore Sottsass in the 1980s, Thomas Heatherwick at Hudson Yards and Little Island, and Hariri & Hariri or Rem Koolhaas today. This time the curators, MoMA's Barry Bergdoll and Columbia's Carole Ann Fabian, even hint at a paradox or two. The man on a quest for private houses and broad highways apart from urban density was the prophet of height as well, but also an early advocate of skyscraper regulation. And his design rules of 1926 responded not just to a building boom in New York and Chicago, but also to urban canyons in the shadow of towers very much like his own. These rules extended New York's first zoning laws, which established yet another unfortunate legacy of Modernism—skyscraper setbacks and their forlorn, empty plazas.

Paradoxes are not always contradictions. Even in building vertically, Wright was out to protect nature from the city and the city from itself. Taller buildings, he reasoned, could stand that much further apart, in an isolation that foretells the luxury condos of Manhattan. Cars could drive in, but strangers might not so easily walk in the door. The pinwheels set buildings as diamonds at a forty-five degree angle to the urban grid, in a city not for pedestrians. Rooftop gardens and corner terraces could safely preserve inhabitants from his own dreams of twenty-four lane highways (seriously). With plans for a Dallas hotel in 1946, light could get in, but people could not look out.

Wright was prescient all the same, especially in light of postwar Latin American architecture—but also in the face of today's more modest ideals of "uneven growth" and sustainable architecture. One may not see his greatest work at MoMA, but one can see the ideas behind it, including innovations in cantilevers, concrete, and glass. With two-foot glass tiles for the National Life Insurance Company in 1925, exterior walls were to seem to disappear. The architect's mistakes have not lost their relevance, but neither have debates over height, regulation, preservation, and affordable housing. The show opened just as plans largely to deregulate the area around New York's Grand Central Station were foundering on community opposition. As Wright put it, in context of building in an earthquake zone, decisions about architecture are "experiments with human lives."

There goes the neighborhood

There goes the neighborhood. Whenever a museum expands or a community gentrifies, someone celebrates and someone mourns. Artists may find themselves on either side. With the destruction of the former Museum of American Folk Art at the hands of MoMA, much admired architects and friends have found themselves on both. Even when Paris transformed itself into the city of boulevards, the city of Impressionism, and the city of lights, photographers drew inspiration from the darkness it was leaving behind. And that act of urban planning became a paradigm for modern architects ever since who have dreamed of remaking life from the top down.

Now opponents can take heart, but so can those who distrust the old world as a playground for the rich. Lebbeus Woods saw architecture as an act of resistance, and preservation had to begin not with quaint, unchanging comforts, but with the ruins of disaster and decay. "Architecture is war," he wrote, and "war is architecture"—as sites of passion and experiment. He had not just to build above destruction, as with his 1989 sketch for an Aerial Paris, but also to uncover, as with his Underground Berlin from the year before, a "freespace" in the "secret life of the city." He had to free himself "from obsession with the end product," the "reassurance of the habitual," and the "tyranny of the object." Yet he could easily bury a city in the sheer weight of his fantasies and its ruins.

Now opponents can take heart, but so can those who distrust the old world as a playground for the rich. Lebbeus Woods saw architecture as an act of resistance, and preservation had to begin not with quaint, unchanging comforts, but with the ruins of disaster and decay. "Architecture is war," he wrote, and "war is architecture"—as sites of passion and experiment. He had not just to build above destruction, as with his 1989 sketch for an Aerial Paris, but also to uncover, as with his Underground Berlin from the year before, a "freespace" in the "secret life of the city." He had to free himself "from obsession with the end product," the "reassurance of the habitual," and the "tyranny of the object." Yet he could easily bury a city in the sheer weight of his fantasies and its ruins.

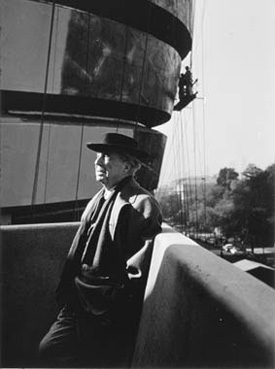

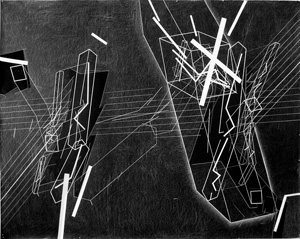

Born in 1940, Woods worked for Eero Saarinen, as a field rep on the Ford Foundation, and then for Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, and he taught at the Cooper Union in New York until his death in 2012. Yet he never obtained a degree or license in architecture, and he completed little or nothing beyond the towering pavilion for a housing complex in China. As the Drawing Center puts it politely, he "concentrated" after 1976 on theory. When the curators, Joseph Becker and SFMOMA's Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, call a retrospective "Lebbeus Woods, Architect," they could be pleading for his legitimacy and his impact. And its largest work is not even a model or drawing, but rather crayon and acrylic on linen. The painting's thick white lines scatter across the black like iron filings in a magnetic field, and he called the field of its abstraction Conflict Space.

Woods did not have to look far to find conflict. He sketched Berlin just before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall, always with the realistic detail and mad plans alike of a visionary, and he borrowed the language of the Vietnam War for DMZ from Terra Nova in 1988. In no time he moved on to cultivate a Zagreb Free Zone, but he did not even need much in the way of humanity to seek a space for freedom. He imagined Inhabiting the Quake in San Francisco as a matter of towers arching upward from an industrial wasteland by the bay or angled planes tiling over mountains, with affinities both to solar panels and scrap heaps. His constructions may float above as a looming menace or come down to a harsh point within an existing courtyard, like "deconstructive architecture" without the trust in left-wing politics. The few shadowy people in his drawings display not form as function or a way of life, but only scale—and they are minuscule indeed.

Nine Reconstructed Boxes from 1999 responds more directly still to the ideal city for those who hate cities. The ground plan does not follow a grid or central axis out of Le Corbusier, and the jagged passageways overhead could well parody the heights that Wright intended as an escape from urban existence. The unnervingly tall towers refuse Modernism's glass skin or even windows, like the Brutalism that he so assailed in Zaha Hadid. When he weaves the shape of cranes the frame of raw steel into his architecture, he could be insisting on the transparency of work forever in process—or on its dangers. One model hoists what looks like an immense torture chair into the sky. This is dystopia as utopia, and its torn shapes offer little shelter at all.

Did he realize how much he replicated the worst of Modernism's tyranny in order to undermine it? Wright and Le Corbusier had their share of unfinished projects as well. Was he aware how little his demand that shattering or neglect "be respected in its integrity" retained the concrete realities of history, pride, or suffering? Much of the work recalls Soviet-era housing or sculpture by Theodore Roszak, like the latter's spheres of polished bronze exposing inner shards to the light. Yet the critic of the object and of architecture as science was at his most massive and futuristic with a Tomb to Einstein, in orbit, its relics nestled in an enormous Greek cross. One can only dread its prophetic fall to earth.

"Frank Lloyd Wright and the City" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through June 1, 2014, Lebbeus Woods at the Drawing Center through June 15. Related reviews look at Frank Lloyd Wright more fully, through his 2009 retrospective and the Wright archives.