Swimming in Pleasure

John Haberin New York City

Henri Matisse: Cutouts and Books

"I will make my own pool." In 1952, just two years before his death, Henri Matisse insisted on an outing to a pool in Cannes to see the divers. Confined to a wheelchair and in his eighties, he tired easily, and he struggled in the day's heat. He was not to make that kind of trip again.

Still, Matisse had found what he needed, and he could still turn a complaint into a boast and into art. Sure enough, he created his own pool, out of cut paper and his dining room. The end opposite the door even has a grid to stand for tiles. Broad bands of white paper run along facing walls, at a level just above the artist's head.  Blue swimmers cross the bands, held only by pins, their bodies diving and surfacing above and below. One can feel light from the room as if one were with them underwater.

Blue swimmers cross the bands, held only by pins, their bodies diving and surfacing above and below. One can feel light from the room as if one were with them underwater.

The Swimming Pool returns to the Museum of Modern Art among Matisse cutouts, after a lapse of over twenty years. Cutouts begin as early as 1930, but they take over his art more or less entirely by the end of World War II. They are his late work and a culmination. Over time, they pare his art back to the grace, challenge, and even subject matter of the early work that helped invent Modernism. They also provide a glimpse of his working methods all along—like his work at the Morgan Library in the book arts. They show him working with his hands, his eye, his environment, and the limits of art.

Motion and repose

MoMA acquired The Swimming Pool in 1975, and a restoration supplies the occasion for the show. Karl Buchberg, the chief conservator, curated it along with Jodi Hauptman and Samantha Friedman. The pins had given way to glue, and colors were fading. One can marvel that so fragile a medium has a future at all. I still miss another vision of water in Claude Monet and his Waterlillies, before MoMA's 2004 expansion drowned its permanent collection in oversized spaces and neglect. At least for a time, though, this immersive experience is back.

It makes clear just what is at stake. For one thing, it shows a refusal to give in. Henri Matisse in the 1940s had endured the failure of a marriage of more than forty years, further displacement by the Nazis, and colon surgery that left him unable to stand for long or to paint. He hit on his découpages, or cutouts, a model for such disparate artists as Stuart Davis and Kara Walker. One can see him on film deftly rotating a sheet while cutting, intent and unsmiling. He never stops in the maybe ten minutes it takes.

For another, the medium made his art a collaboration. Others first applied gouache to artist papers, just one color per sheet, and then rearranged cutouts for hours until he pronounced them done. He makes it look easy, but he sure made it hard on others. His art's apparent ease only partly disguises a studied upheaval, going all the way back to the wide-open color of The Red Studio or The Dance forty years before. The artist who boasted "I never retouch" first used cutouts as a way of trying out ideas, starting with his 1930 murals for the Barnes Foundation, dragging around the pieces with string. In a design for a stage curtain, one can still see the thumbtacks.

Collaboration of another kind, on other arts, impelled him further to the new medium. Matisse used it for stage design, magazine covers, a rug, and Jazz, an illustrated book published in 1947. He used it for a priest's robe in perhaps his masterpiece, the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, in the south of France. In each case, he pushes toward decorative art on the one hand and abstraction on the other, before drawing back into a space all his own. For the chapel's stained glass, Celestial Jerusalem has nothing but a tumble of plain geometry and color, while Pale Blue Window returns to leaves of the tree of life. He has found both motion and repose in his subjects as well as his art. Along with the swimmers, he outlines dancers, bathers, circus acrobats, and clowns.

That balance helps explain the popularity and sheer pleasure of the cutouts. Timed tickets vanished quickly. There may be something otherworldly in Memories of Oceania and Oceanic art, a near abstraction from 1953 that long graced MoMA's corridors. There may be sexual tensions in the swimming pool, with women amid monkeys and pomegranates, like fruit of the tree of knowledge. There may be an expression of loneliness, guilt, Nazi persecution, illness, and fatigue, not to mention the sheer tension of line and color. Yet once again Matisse tempts one to think that, for a moment, all tensions are resolved.

For some, Matisse's temptations come too easily, especially compared to Pablo Picasso. By the time of the cutouts, he had become an institution. For others, his calm is a welcome relief from the sexism and egotism of Picasso's women. Now, rivalries among Modernism's greatest miss plenty from the start, and late Picasso deserves more than a hasty dismissal, but it does arise from a career of passionate reinvention. The pleasure of the cutouts is to see a very different older artist, seemingly above love or hate. It is to recover the sweep of Matisse as a whole.

Cutting, drawing, and color

The Swimming Pool has all of that—the persistence, the collaboration, the reworkings, the reach toward another medium (architecture), the motion, the repose, the tension, and the temptations. It also has one last hallmark of the cutouts, as the pool becomes his own. Matisse takes as his subject an interior shot through with a larger world. It could be stage, a pool, or a chapel flooded with light. If something darker inflects the joy, it lies here. Confined to interiors, he turns inward to the architecture of his imagination.

That turn took place in stages. First comes work for Barnes, the theater, ballet, and print. With The Fall of Icarus in 1943, cut paper evokes, Matisse observed, the "sensation of flight." With its riffing, jazz seems natural for a medium of repetition and rearrangement. Riffing extends to language as well. Pierrot le Fou becomes Pierre à Feu—the fool in a romance now a man on fire.

Jazz is cutout at its closest to collage, with overlapping colors. At book length, it also approaches narrative. Narrative reaches its end in 1950 with the story of a storyteller, The Thousand and One Nights. "She saw the morning appear," one reads, and "she fell discreetly silent." By then, though, Matisse had started to silence the narrative in himself. He had had his first encounter between cutouts and their surroundings in his studio.

Jazz is cutout at its closest to collage, with overlapping colors. At book length, it also approaches narrative. Narrative reaches its end in 1950 with the story of a storyteller, The Thousand and One Nights. "She saw the morning appear," one reads, and "she fell discreetly silent." By then, though, Matisse had started to silence the narrative in himself. He had had his first encounter between cutouts and their surroundings in his studio.

Oceania from 1946 places birds and ocean life in rows on wide expanses of canvas. The tension between the grid and life looks familiar from art today. Matisse was not sure that the small white cutouts would stay there, but he knew that they were no longer in the service of something else. Then comes an explosion of motifs, from floor to ceiling. The work is not quite site specific, since he could rearrange it as needed to fit its surroundings. But then The Swimming Pool may have another life yet as well.

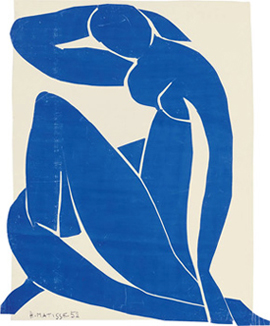

The chapel is Matisse at his most luminous, and the 1948 commission took him three years. His most magisterial, though, are his four Blue Nudes (not the early painting in an impressive copy by Hayley Barker). They also make clear his "negative spaces." They depend on cuts and the gaps between sheets, as limbs and body cross. Contemplation becomes a physical act, while art creates a space for contemplation. After two final rooms for decorative murals, the story is done. Those have images of fruitfulness, in ocean life and sheaves of wheat, but the dedicated interiors bear more fruit.

For all the assistants, Matisse's pencil studies are already close to the finished work. Cutting for him is drawing in color and space. If one thinks of the cliché about Picasso as line, Matisse as color, cutouts made color and line inseparable. Maybe war changed everything, just as it had for Matisse in World War I, at his most enigmatic and darkest. One can see, though, why cutouts allowed a renewal. They brought with them the elements of his art.

The author's name

Matisse worked for eight years on a book of poetry by Charles Baudelaire, but when he came to the title page, he still left something out—the author's name. Call it a Freudian slip or an innocent mistake. The project was doomed as it was. Yet the slip could serve as a parable for the artist at work. "Graphic Passion: Matisse and the Book Arts" shows his delight in the medium and in collaboration, but also his frustration every step of the way. He had a habit of frustrating others as well.

Books were sure to intrigue Matisse, especially late in his career. They allowed him the company of writers and words. As early as 1918 he collaborated with Pierre Reverdy, adding the slashing parallels of his shaded nudes to Reverdy's sensual, inner-directed poetry. Both could claim to have influenced Cubism, Surrealism, and the course of modern art. He later planned an edition of Ulysses in Paris with James Joyce himself. He felt art and literature as part of a single effort, engaging all the senses.

Book art also allowed or even, Matisse felt, obliged him to experiment with printmaking. He tried etching to soften the edge of his arabesques, much like his pencil, and the Morgan displays a copper plate. He published three volumes of his own drawings around 1920, using photogravure and collotype to mirror their density. A print of The Plumed Hat, after a drawing related to the painting in Washington, is all but indistinguishable from the original. The correspondences only grew as he turned to scissors in the 1950s. He used pochoir, or stencils, to apply the same colors as in his cutouts.

Not that he was satisfied. Even then, he hated losing the edge of cut paper. He distrusted the whole idea of a reproducible medium, even as he embraced it—sometimes in pricey special editions that replace a more generic facing page to the title with his work. The time spent designing fonts or ditching text entirely for handwriting shows his dedication, but also his obsessive control. He rarely subordinates himself to text, preferring portraits or, to an author's chagrin, prints that he had already published to simple illustration. He and Joyce agreed to a series inspired by the Odyssey rather than the novel, so that the brothel scene becomes a nearly abstract swirl of bodies, like a forest in motion.

And the publisher hated it, which is why that artist's book never came to be. At least the failure of Baudelaire's Les Fleurs de Mal was inadvertent. An accident in the studio destroyed work to date, and the project never recovered. More often, though, Matisse and the author fought back. He and Reverdy reprinted the text after the editor played artist, printing it in several colors. He stood fast when another editor, given the cathedral of Notre Dame behind a joyful crop of trees and their reflections in the Seine, saw only that Matisse had reversed the two towers.

The Morgan imposes its editorial control, too. Labels high on the wall add barely relevant themes, such as "Creative Differences," to a largely chronological presentation. Wall text for each work comes with snappy but intrusive titles, such as "Turnabout Is Fair Play" and a quote from Friedrich Nietzsche. Jazz from 1947 takes pride of place, but with few examples. One can see it begin as a treatise on color, driving his concern for matching colors precisely in stencil. And then Matisse falls back instead on the free associations that link him to jazz.

Matisse approaches a print in stages, as a process of paring back. It is fun to discover him sketching in the Bois de Bologne, to capture a swan for Stéphane Mallarmé, the symbolist poet. On the page it rears its head with the same fluid motion as in his nudes, the fall of Icarus, or a decidedly feminine animal's head for the myth of Pasiphaë in love with a bull. And he thrives when a book departs from the literal along with him. He illustrates the sound poetry of Poésie de Mots Inconnus (or "poetry of unknown words") with white on black that could pass for a wave, a woman, sedge by the waters, or nothing at all. With the handwritten Verve and Jazz, letters spin out into two dimensions, in a poetry and a language all their own.

I thought again of One Thousand and One Nights: Elle vit apparaître le matin. Elle se tut discrètement. ("She saw the morning appear. She fell discretely silent.") For Matisse, a book holds a narrative up to art, but art may reply with a stubborn silence.

Henri Matisse cutouts ran at The Museum of Modern Art through February 10, 2015, "Graphic Passion: Matisse and the Book Arts" ran at The Morgan Library through January 18, 2016. Related reviews look at Matisse and Picasso, The Red Studio, Matisse and textiles, and Matisse in retrospective.