Is Assemblage Still a Threat?

John Haberin New York City

Addie Wagenknecht, Christine Rebhuhn, and Bob Smith

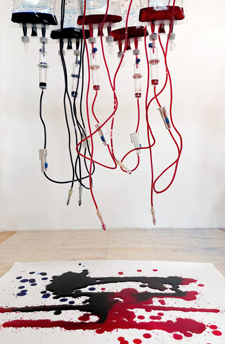

An IV bag dripping what might pass for fresh blood. Fragments of a car or motorcycle that might have crashed, but are now a site for remembrance.

From the start with Marcel Duchamp, found objects have posed a threat—even when the threat is primarily to the status of art. Yet their display could also be wry or reverent, even when reverence is the butt of the joke. Duchamp's urinal, signed R. Mutt, resembles a sculptural niche from which the blessed Virgin has only recently departed. So it is when Addie Wagenknecht treats that drip as a raucous kind of drip painting, taking shape over time as an American flag.  So, too, when Christine Rebhuhn makes assemblage feel right at home, with a promise of background music still to come. As for Bob Smith, the threat is inseparable from a sense of wonder at the darkness.

So, too, when Christine Rebhuhn makes assemblage feel right at home, with a promise of background music still to come. As for Bob Smith, the threat is inseparable from a sense of wonder at the darkness.

"The difference between men and boys is the price of their toys." When Smith added that text as the title and one last layer of a spooky assemblage, was he just playing around? This and other works from the early 1980s cut way too close for that, in a show called "Art Remains a Witness to a Life." The words appear on a small scrap of wood as if they had always been there, as a found object and a sign of their times. It covers the bend in a pipe, so that together they might be a gun. It might be a toy gun, but then it might go off any minute.

Blood on a cracked glass

A hostile critic might blame Addie Wagenknecht for a "sterile installation," but but her gallery boasts of it. Not that it looks hospital safe, not by any means. IV bags drip their contents onto paper laid across three pedestals. Seeming pools of blood lie everywhere. Some are bright red, so that one can almost feel the blood pouring out of one's veins. Some have turned almost black from the inhospitable air.

I trust that my next major surgery will go better, but then I am just one patient in a dangerous experiment, the American dream. America, she says (quoting, I imagine, Robert Frost), is hard to see, but the American flag will take shape on all three tables over the course of the show. The bags hold not blood but red and blue ink, and she has timed their flow. On opening day, the IV tubes looked clean and closed, ending in a clip that might fit into the charger port on your phone. The drips and the white of the paper had not yet settled into stars and stripes, while the third sheet bore no visible marks at all. The experiment was to become more certain and less chilling.

American Flag is just the latest in her focus on the flag and the dream. She compares the latter to a cracked screen on an actual device. "We often view the world via and by it," she observes, "for months or years before we even bother to try to fix it." I had to remember Stephen's lament for Irish art in Ulysses as "the cracked lookingglass of a servant." Back in 2017 Wagenknecht ran through rippling, computer-driven variations on a flag, as Believe Me 1.2–1.4. The gallery, which specializes in new media, also posts them online, although it declines to display them with the drips.

They are not a pretty picture, and the show's title is less hopeful still. "Every Day the Same Again," it runs, but again one can take at least some comfort, for every day is not at all the same—not when the flag is slowly coming to be. Her older videos evolved, too. Think of their numbers as designating versions of an app. They come with high-tech complications as well. They were "minted with NFTs (non-fungible tokens) to signify the artwork's blockchain certification."

Maybe, but some things really are hard to see. Certification could be a mere distraction from the perils and promise of the dream. Trendy as it, the bitcoin bubble may crash long before Americans see the cracks. These are not the only flags in town either. Wagenknecht has a more lasting source in flag paintings by Jasper Johns. Her pooled ink hints at the thick textures of his encaustic.

One could accuse her of looking away. Blood is an emblem of longstanding wounds, but their substance goes unmentioned. Johns, for that matter, did not always paint the flag in red, white, and blue. Still, it takes real doing to encompass sculpture, drip painting, process art, and new media, and this is not so sterile an installation after all. I can still almost smell blood. When the Whitney Museum opened in the Meatpacking District with a display of its collection as "America Is Hard to See," it could not have known the half of what was to come.

Object-oriented anxiety

For Christine Rebhuhn, music is just part of life. Life insists on it, allowing music to break into her home. A black table has split apart, with a mellophone between the halves of its no longer vicious circle. The table might press in, holding the instrument in place, or the instrument might hold the table open. Either way, it fits, the flaring end of its horn pointing up, level with the table's surface. One can almost hear the silence.

No single component is all that unusual, but together they are all wrong. The cheap table looks way too small, the mellophone too large, as if a trumpet had gotten out of hand. It is at once too loud and too silent. But then just entering a gallery can upset a sense of belonging if one is looking for home. Think again of Dada or Rauschenberg, his collaborators, and his "combine paintings." The press release by Torey Akers speaks of a philosopher's "object-oriented ontology," as opposed to a human-centered world of knowledge and action, but then objects in art are never just themselves.

No single component is all that unusual, but together they are all wrong. The cheap table looks way too small, the mellophone too large, as if a trumpet had gotten out of hand. It is at once too loud and too silent. But then just entering a gallery can upset a sense of belonging if one is looking for home. Think again of Dada or Rauschenberg, his collaborators, and his "combine paintings." The press release by Torey Akers speaks of a philosopher's "object-oriented ontology," as opposed to a human-centered world of knowledge and action, but then objects in art are never just themselves.

Not that Rebhuhn is out only to shock, not even in a show called "The Breeze Will Kill Me." She has nothing as mundane or inappropriate as Duchamp's Fountain or a tire around a taxidermy goat. One might ask instead about her universe and her anxieties, much as Rauschenberg called his goat Monogram, irony intact. That table and mellophone are her Last Bare Chamber (of My Heart). Music and furnishings keep returning, with flutes nestled into the vents of a drop ceiling or a black window frame. In a version not on display, the horn of a trombone holds a window open, while its slide recalls just how it might have opened.

Nature keeps turning up as well, with ceramic flowers and stuffed birds. It is about time that taxidermy in art made a comeback. Here nature, too, has a domestic setting. These are small songbirds, not free flyers. If you ask why the caged bird sings, her uncaged bird is silent. Side mirrors from a Volkswagen hold a photo of man's proverbial best friend.

One last motif is masculinity, the world of cars like that Volkswagen—and Rebhuhn might be lamenting its loss or its bitter consequences for women. The reflective surfaces of motorcycle mirrors have given way to burning candles, as illumination or in mourning. The piano's remains hold the photo of a cowboy, nearly life size, striding onto a horse. Men stand behind a police barrier in what might be a Depression-era photo, within an elegant curved wood frame. What are they so eager to watch? Rebhuhn does not let on, but they, too, bring a dog.

If her vocabulary is limited, its strict limits contribute to that sense of anxiety. Objects here can belong to more than one part of that vocabulary as well. That piano might have come from a privileged household, as at once a grand (or baby grand) instrument and furniture. An uncaged bird is part of nature, but also a maker of music. Two birds rest on stirrups, hanging down from a black surface in the shape or a piano lid or saddle. More taxidermy and flowers rest on chrome bicycle handles as Ride or Die.

Still, Rebhuhn keeps death at a relatively safe distance, even when it intrudes on home. Her interest in interior design and interiority also accords with contemporary echoes of Minimalism, as with Diane Simpson. Now in her eighties, Simpson might isolate an element of architecture, like a window or a banister. Even when she moves directly to abstract sculpture, she may give it a wood grain. At a given moment, the work can be lovely, ordinary, or downright funny. Rebhuhn may not have much of a sense of humor left after her view to a kill, but a world of objects need never be simply inhuman.

The price of his toys

Bob Smith paid a price for playing around, dead of AIDS in 1990. Yet he was taking the long view. An old star map forms the background, and blond wood peeks out from amid a darker lamination, like the profile of a charioteer or something more dangerous. He had in mind, too, more contemporary or future tastes in covering the base of his shallow box with blue glitter. It embellishes the enlarged initial of his signing the work as well. Merely collecting scraps was his signature as well, as an art form and the scraps of a life.

He had his Homage to Joseph Cornell, and his boxed assemblage does share Cornell's Surrealism and memories of childhood. Yet it seems less ready-made and less dependent on juxtapositions, so that each box becomes a landscape or a theater. It may be a cave, a dark forest, or the night sky. Some boxes have lighting, behind a partitioned ceiling, unifying the scene while leaving it that much more unknown. Every so often the construction overruns the box at that. Wood that serves as trees peeks out through the top, where it looks like the handle of a vintage sword or, perhaps, its source in chair caning.

Of course, Still Life with Chair Caning is a work by Pablo Picasso—another indication that Smith may be playing around, but only because he is making art. That quote means something different anyway when the adult is an artist whose works hardly sold. (Some attribute the line to Malcolm Forbes, the publisher of the business magazine bearing his name, who could afford pricy toys.) And Smith includes cheap toys as well, like small plastic horses. He could have been a lifelong man-child, but then, as another title has it, there are Things Money Can't Buy. Another work looks like all-over abstraction, but he has stuffed a box with shredded dollar bills.

This is a time of rediscovery, between attention to diversity and a search for the next big thing. The gallery calls him "a well-kept secret," putting a positive spin on his lack of notoriety. Still, Smith seems not to have worried all that much about inside and out. He passed the 1960s in Europe, mostly Madrid, and returned to New York for what truly was a downtown scene. He tried his hand at set design, collaborated like Robert Rauschenberg with dance, and dedicated a work to Larry Rivers, the painter. He must have cherished their late nights for the darkness. White rabbits look cuddly enough as sock puppets, but they are "spider rabbits," after a play by a friend, Michael McClure.

Gender identity is also newly important, and the AIDS crisis has never fallen out of memory. David Hammons, Gordon Matta-Clark, Alvin Baltrop, and Peter Hujar have all made art from the Hudson River piers, once a gay pick-up spot—and Smith names one work, with its brooding red sky and bare, fallen timbers from a three-masted ship, for the piers. Elsewhere he includes a photo of himself, sprawling in unfulfilled pleasure. But the melancholy and the wonder preceded real-world desperation. Mars, the angry planet, presides over a starry sky in place of the full moon. Another work is a full-blown witch's Sabbath.

Still, do not underestimate the child's play. The witch may be only costumed for Halloween, and she has brought a pumpkin. The bad news keeps coming, but in quotes, like a newspaper clipping—"The Tragic Facts About Whales." Smith has his limits, just as he worked in a space apart. The few paintings do not have half the impact of the boxes, because there the juxtapositions are within his imaginings and not the gallery. Just enjoy a reminder of boy toys without the egos or the anime—in art that the mainstream could never absorb.

Addie Wagenknecht ran at Bitforms, Christine Rebhuhn at Thierry Goldberg, and Diane Simpson at JTT, all through November 13, 2021. Bob Smith ran at Martos through June 18, 2022.