Landscape, Light, and Lives

John Haberin New York City

Matt Bollinger and Eleanor Ray

Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly

Landscape painting and photography can draw on at least two traditions—charged with light and charged with lives. From the Dutch golden age to color-field painting, artists have used color to explore the relationships between light and space. And artists from the Dutch to the Ash Can School and beyond have used landscape to situate people in politics and communities.

Postmodern critics could disdain the division. Even a documentary realist tests the limits of art, and even an Impressionist was a painter of everyday life and a changing society. Still, not everyone can make light illuminate lives. Matt Bollinger uses an intense light to examine his own life, along with his alter egos as a sci-fi writer and a scientist. Eleanor Ray paints with an awareness of past artists who shaped the land and its inhabitants. In photography and video, Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly evoke artistic and religious communities some two hundred years apart.  All seem devoted to appearances, but as a sign of what it might take to penetrate within.

All seem devoted to appearances, but as a sign of what it might take to penetrate within.

Counting to three

Matt Bollinger calls his latest work "Three Rooms," but try not to worry if you have trouble counting to three. His paintings show not just fragments of a house, but also of a life. They are tantalizing fragments at that, because they add up only slowly, and I, too, lost count. There is no mistaking, though, the impression of a home bathed in light. It varies from the pale yellows of an early morning sunlight to shades of blue for late afternoon into night. Both have an eerie saturation that helps to unify an unfolding display.

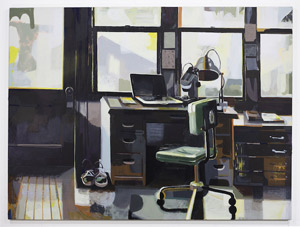

Canvases of varying size hang densely, jumping casually from room to room. The largest contain a bed, a dining table, a living-room table with sofas to either side, a greenhouse set, and a desk ready for work. That is five rooms right there. They avoid a larger perspective to help in navigating them, apart from hints of a deep view toward or from the entryway. Painted wood models offer further clues, but they stick mostly to that passageway and half-open doors. The tabletop constructions are freestanding anyway, so that one sees them at least half the time only from the back.

The rooms are empty, as if Bollinger had stepped out the moment before, while smaller canvases close in on what he has left behind—a laptop and turntable with a record in progress. His absence, down to sneakers on the floor, adds to the strangeness of the light. It is a raking light, with panes of color suspended in midair. Unusual contrasts in Flashe and acrylic deepen the shadows, with a blue or greenish brown in daylight and a warmer brown or more bright yellow interrupting the blue. The study has a desk lamp, but off, and who needs it? These rooms have an impressive array of windows.

They invite him to work, but what exactly is he doing? One cannot read the label on the LP, but a note on the laptop names Ursula Le Guin, and a gallery handout speaks of the show's subject as a science fiction writer, too. The desk, though, also holds a microscope, and a title identifies the room as a mycologist's office. A stop-action video picks up that theme, as brushstrokes morph first into mushrooms and then an insect perched on the bark of a tree. Circles pick up dabs of color at their center before settling down to petri dishes awaiting specimens. Still, this is a home and not a laboratory.

It might belong to an amateur scientist or just a homeowner delighted by his proximity to nature. The confluence of art and science could also refer to the painter as observer and a student of natural histories. It places him in a long tradition. The sense of a life in progress also parallels art as a process. Its making appears explicitly in the video, with its palpable brushwork, or the backs of the wood models. It appears implicitly, too, in the paintings.

Things there look impeccably clean and up to date, like the microscope and the high-end turntable. The bed has sharp corners, and the bare tables of the dining and living room bring out their geometry as well. Yet brushstrokes end abruptly, as if searching out the light one mark at a time. Highlights fall as they will on the study windows, as if the glass were an abstract painting. A loved one does appear once or twice, named Dawn, as if she, too, brought light. The show's real subject might be its own coming to be.

An artist's landscape

Eleanor Ray has traveled a long way in search of a pale light—to Tuscan interiors, the high Texas desert, the Great Salt Lake, and the great western plains. Any one of them sounds more natural and immediate in its presence than the next, but other artists, she knows, have been there before. Ray's Italy includes San Marco in Florence, with frescoes by Fra Angelico, and the Scrovegni chapel in Padua, with frescoes by Giotto a day trip away. Donald Judd made Marfa, Texas, an arts center, and the Great Salt Lake just happens to contain Spiral Jetty, by Robert Smithson. I can still picture Smithson on film almost dancing along it in pure joy. As for the West, with its towering hills, what could stand more for America in photography and art?

Her sense of the past recalls a true painter's painter, Fairfield Porter. Like him, too, she embodies an abstract painter's ideal of landscape. At a time when Abstract Expressionism was helping to revive the breathtaking leaps into space of the Romantic sublime, Porter's colors evoked a crisp light, a bracing air, a summer's heat, and an unflinching eye. Yet his deft touch, so unlike Northern Romanticism and nineteenth-century Danish art, promised that a brush would never be just a substitute for the finer point of a pen. Now Ray, too, sees landscape through the eyes of an artist. In fact, she comes to it as already shaped by art.

Her sense of the past recalls a true painter's painter, Fairfield Porter. Like him, too, she embodies an abstract painter's ideal of landscape. At a time when Abstract Expressionism was helping to revive the breathtaking leaps into space of the Romantic sublime, Porter's colors evoked a crisp light, a bracing air, a summer's heat, and an unflinching eye. Yet his deft touch, so unlike Northern Romanticism and nineteenth-century Danish art, promised that a brush would never be just a substitute for the finer point of a pen. Now Ray, too, sees landscape through the eyes of an artist. In fact, she comes to it as already shaped by art.

Not that Ray is taking selfies in front of the work of others. Spiral Jetty is recognizable enough, although at a distance and from a high point of view. A low point of view puts one in the midst of Montana and Wyoming grasses, while reducing in scale their distant hills. Judd's Chinati Foundation becomes just windows and porches angling in and out of the picture, while this view of Renaissance art amounts to little more than a composition over wood furniture and a doorway, like a poster in a dorm room, or the very corner of an angel's dress. Taking them in before reading the press release, I could congratulate myself for recognizing them. As for Ray and others, they do not appear at all.

The anonymity helps turn public spaces into private experience, often a suitably awkward one. For decades now, the jetty has vanished into the lake and reappeared with changing climate, but here it seems stranded on something more like sand. Ray's panels, just six or eight inches on a side, add to the sense of discovery and intimacy. To confirm the displacements, none of earlier artists worked in oil—and neither Judd nor Smithson in painting. Besides, the asymmetry of Ray's compositions, building on window frames or the architecture within a fresco, brings them closer to Piet Mondrian than to the Renaissance or Minimalism. She just happens to slow Mondrian's urban boogie-woogie way, way down.

Her light matte colors do recall Porter, much like the broad areas of color in tobacco fields for Keris Salmon. She also drags her brush slowly enough to allow the ground to add gradations. As the shadow of a window slips down over a ledge, it shifts slightly to one side and deepens from gray to brown. Views through a window look like postcards already framed. The blackness through an open doorway in Florence, with a rope across the wall, tells you where you can and cannot go. Not much is going on here, because artists have been working and reworking that little all along.

William Carroll deals in gradations, too, and an experience just short of recognition. The overlapping silhouettes of buildings, in red or black, create the sense of exploring New York at sunset or well past midnight, like Robert Frost as "one acquainted with the night." Everything looks plainly geometrical, like modern architecture or rural houses for Michael Gregory, but also freehand, with corners and windows never quite lining up. It may come as a surprise that he works in spray paint, on canvas or panel, but it allows him also to explore shades of gray. Even with a spray can, he also manages to leave a rectangle of white in each window, while the red buildings omit windows entirely in favor of a deeper burn. I could recognize them all, I felt, without being able to name a single one, and I, too, had become acquainted with the night.

The spirit within

Give it time. With their title, Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly speak of unknown others, elsewhere, in the past tense: When the Spirits Moved Them, They Moved. Yet their work proclaims a spontaneity that precludes narrative time as well. It is about holding onto that moment, in the present or the past. The spirit, it suggests, could also move you.

The main gallery has large color photographs to introduce the place and moment. There will be both temporal and physical leaps ahead. Simply coming upon the three-channel video is to enter an inner sanctum. It unfolds in a Shaker meeting house in Kentucky, where "a beautiful stillness" gives way to "heavenly Orders in great abundance"—and it conveys both the stillness and abundance. Dancers rise on their toes in unison or as the spirit moves them. One dancer falls to the ground only to rise again.

The quote comes from an extended statement in the first person. It may be a fiction rather than documentary history, but it is convincing enough. It sets things on a Sabbath on the birthday of Ann Lee, known as Mother Ann, who brought the Shakers from rural England to America—a tradition recalled by Anne Buckwalter as in contemporary painting as well. Starting in Mount Pleasant (then New Pleasant), New York, the millennial movement reached Kentucky at the start of the nineteenth century. The account describes the meeting as moving from prayer and orderly circles to that heavenly disorder, much as one sees. One might never know that communities like this one have long since died off apart from one in Maine (with, the artists note, exactly two members), in no small part because they practiced celibacy.

One might never know, too, that one is anywhere but in the present. That inner sanctum is awash in sunlight, just like shots of the exterior, which fill mostly the side channels in no particular order—least of all a story line. The actors are young and dressed for a modern dance rather than a religious order. They also jump on and off benches much like one for viewing in the gallery, sacrificing evangelical fervor for an inner discipline. Even the spare white house accords with contemporary tastes. Perhaps it must, since it is still standing.

Still, there is no denying the narrative. The dancers move as they do because Kelly has choreographed them, although in the spirit of collaboration, like children for Rineke Dijkstra or a "Hawk Dance" for Simon Starling. Ghani has a background in film. There is also no denying the barriers. Shots include a stone fence and a wooden one, while the side of the building that one sees has no windows. The video keeps returning to them as if to shut you out.

Then again, it might also have shut you in. The Shakers were, after all, a sect apart from and often in defiance of legal authorities. (It refused oaths of allegiance, tried to stay alive by converting others and adopting children, and called for pacifism.) The work's real subject might be the limits of a shared experience, even an ecstatic one. Art, too, can be a privileged community or just plain arcane. Come to think of it, many surviving Shaker halls have become museums.

Matt Bollinger ran at Zürcher through March 2, 2019, Eleanor Ray at Nicelle Beauchene through February 10, William Carroll at Elizabeth Harris through February 9, and Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly at Ryan Lee through February 16.