They Cover the Waterfront

John Haberin New York City

On the Waterfront and a Changing Brooklyn

This Place We Once Remembered and LoVid

The Brooklyn waterfront will never look the same again. At the very least, it may move inland and upstream, leaving what many call their beaches and homes behind.

So it may if climate change is real, and it is, but the waterfront has long been changing. Who knew what it took to create a great port city, and who can keep up with its changes, from the arrival of the Dutch to today? "On the Waterfront" lacks the star power of Marlon Brando in the film of that name, but it is more than just a warning or a historical recreation. Its fourteen artists move easily between past and present, to make Brooklyn's deep history their own. They look for evidence to old maps, human relics,  DNA sequencing, and observation, because a lot can happen in a lifetime, much less over so many years.

DNA sequencing, and observation, because a lot can happen in a lifetime, much less over so many years.

One goes to Wave Hill for the richness of nature by the Hudson River and the city, all the more so in that nature is filtered through art. That includes the picture perfect views and perfectly mannered lawns. Nature at its wildest, in the broad, twisting trunk of a silvery white copper beech, bears a plaque with its family, genus, and species. It includes, too, the summer show of winter artists in residence, with their own delight in landscapes, real and imagined—very much like the landscape in which they appear. This year's crop sees it all as an extension of their personal and cultural heritage, but there is more lasting past summer. For LoVid, at the far end of a pristine lawn, that heritage is still running on network TV.

Crossing Buttermilk Channel

Curated by Maddy Rosenberg of Central Booking, "On the Waterfront" retains the gallery's focus on the artist's book and the confluence of art and science. Organized in conjunction with the New-York Historical Society, it also brings a dedication to New York history. The artists draw on the Society's collection for ideas and images, including postcards, Tiffany lamps, and The Course of Empire, the epic paintings by Thomas Cole. If Cole has you thinking big and book art has you thinking small, the show has room for both in the warehouse space of the Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition, at the very foot of Red Hook. Step outside, and Staten Island looms ever so close. This is what the show's subtitle calls "A View from the Coast (Line)."

New York often means Manhattan, and the Society's winter shows followed black and white artists to Harlem. Climate change in art most often means a state of emergency, as with Josh Kline at the Whitney (who pictures young, white office workers in the Financial District after the coming flood). Duke Riley restricts his view of the coast to plastic waste at the Brooklyn Museum, which really should get involved in a community-based show like this one. "On the Waterfront" takes instead the long view—for Helena Kauppila, the genetic code of (just maybe) the last universal common ancestor, in painterly text art with a nod to Jasper Johns alphabets. Others ask what change has meant for geography, housing, and life today. Patricia Olynyk transforms her "hybrid micro-organism" into augmented reality and a plain old board game.

Such a history can be elusive. Olynyk has enough roots in painting to make her game an abstract tondo. Diane Lavoie turns her sources into mottled blue and brown textiles, spilling out onto the floor. Ellen K. Levy treats The Course of Empire as Palimpsest, a colorful abstraction of overlapping canvas and sculpture. But then Cole meant his series not in praise of colonialism, but as an allegory of decadent civilization in Europe. It was up to the Hudson River School and America to make it new.

Others are more literal, up to a point. Judith Eloise Hooper adopts three Brooklyn points of view for landscape on ceramics, including Red Hook. Elena Berriolo renders plant specimens in spare but brushy ink and thread. Paul Tecklenberg makes cement milk bottles, each with a print of the harbor. After all, the port of New York came to life when settlers dredged Buttermilk Channel, between Brooklyn and Governors Island. Still, you are more likely to think of bottled water and Riley's disposable plastics.

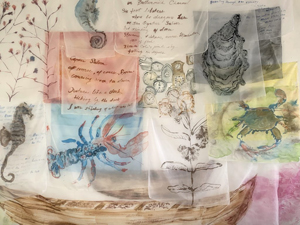

Some do best of all by uncanny juxtapositions, of media and of histories. Sabra Booth frames her views of the Gowanus Canal within old ship portals, Graciela Cassel sets her Governors Island Crossing within bright blue and slightly goofy furniture, and oyster beds for Margaret Craig become biomorphic sculpture and hanging lanterns. Clipper ships pass beneath marine organisms like stars for C Bangs, while an Oyster Saloon for Desirée Alvarez fills the sky, where clocks mark the passing of time. Her silky scrims and fluid colors wave amid currents of indoor air. She also solicits quotes from high-school students, although thankfully the artist remains in charge. They remind one that past and present will unfold in the future.

Rosenberg collaborates with Susan Rostow on a miniature theater and study room for Brooklyn's history. Rostow's sculpture takes its place in stage sets akin to dollhouses, but with early Brooklyn architecture, while Rosenberg's vintage maps become a jigsaw puzzle awaiting completion. Heading home, I crossed by Brooklyn ferry, packed with parents and small children heading back from the beach. It took me through Buttermilk Channel, past gentrification in Brooklyn and Long Island City along the way. Climate, one can safely assume, was on no one's mind, nor art. There will be puzzles for those children when they grow up all the same.

Roots: as seen on TV

For the eight artists in "This Place We Once Remembered," cherished memories are all too easy to lose apart from art. They still have their sense of place, but where? Is it Wave Hill's Glyndor Gallery, in the Bronx by the Hudson? For Dana Levy, the mansion appears, as one title has it, as A Ghost from the Future. Is it her half-remembered media, of stained glass and a magic-lantern slide show? Is it her ghostly prints or all in her head?

Is it the sunroom, where a ninth artist, Jacq Groves, constructs seeming fragments of flesh and bone, along with the folk remedies that he hoped would keep them alive? Is it Israel, Germany, Egypt, Japan, Brooklyn, and the Afro-Caribbean diaspora, where the cast has its roots? Ezra Wube presents Ethiopia as a seeming paradise, but his stop-action animation gives voice to interviews with the country's inhabitants as mostly lost hopes. Is it the ground at her feet for Ariel (or Aryel) René Jackson, which to her is ancestral ground? She invokes it in a loose grid of soil, lime, and cement. As Paloma McGregor puts it in performance, in the language of St. Croix, All of Us Are Here.

The artists share an interest in calling colonialism and history to account, although I do not always see it in their work. Yelaine Rodriguez dresses in white and feathers as a deity standing guard over shores and caves, but she is too busy dancing about and having fun. You may find yourself joining in. Saya Woolfalk claims an entire Encyclopedia of Cloud Divination, in prints and video, but the colorful flowers and human hybrids belong just as much to present-day cartoons and to Wave Hill. I did not catch performance by Zachary Fabri or Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow, but I did head to Wave Hill House for more. There LoVid might be speaking for them all with "Tap Root."

The artists share an interest in calling colonialism and history to account, although I do not always see it in their work. Yelaine Rodriguez dresses in white and feathers as a deity standing guard over shores and caves, but she is too busy dancing about and having fun. You may find yourself joining in. Saya Woolfalk claims an entire Encyclopedia of Cloud Divination, in prints and video, but the colorful flowers and human hybrids belong just as much to present-day cartoons and to Wave Hill. I did not catch performance by Zachary Fabri or Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow, but I did head to Wave Hill House for more. There LoVid might be speaking for them all with "Tap Root."

Video has roots, too, only not the kind that run deep into the soil. And LoVid has staked its name on looking outward and looking back. In a world of new media, its very name sounds low res and low tech. A title still wonders What's on TV. At Wave Hill, the work itself is digitally printed, but on fabric. In a high-tech world, a woman's work is never done.

In real life (or make that IRL), LowVid is male (as Tali Hinkis and Kyle Lapidus), with a man's due certainty. That title without a question mark is not asking you what's on TV but telling you, and they have every right. They did, after all, convert a room in 2014 into a compendium of TVs, from the first picture tubes to the latest and smartest. It went quite well with the Experimental Television Center elsewhere that year, and it would go quite well with "Signals" at MoMA this past spring. Here, though, they bring something new, a touch of craft and a touch nature. In work from the last three years, nearly every print is a landscape, complete with flowers, spiders, and tendrils.

One landscape picks up on Wave Hill's luxuriant greenhouse, where more plants spill out on the grounds out front. Larger prints have the scale and patterning of tapestries. (One must step carefully around diners in the café to see them.) If tapestry is a decorative art, these take their patterns from good old low-res pixilation, with distorted colors to match. One more title captures the ambiguity, as Music for Alpines, a pun on Music for Airports. Brian Eno's high-tech background music has become a room with a view.

"On the Waterfront" ran at the Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition through April 23, 2023, thanks to Central Booking and the New-York Historical Society. "This Place We Once Remembered" ran at Wave Hill's Glyndor Gallery through August 6, LoVid through December 3.