Nostalgia for the Future

John Haberin New York City

A Billion Dollar Dream: The 1964 World's Fair

Pirouette: Turning Points in Design

The Queens Museum does not "do" nostalgia, at least not willingly or well. It is too busy making up for its past, with artists from the Dominican community in Corona and the greater diversity of Queens.

Besides, it hardly has to. Those of a certain age will remember the building as the New York City pavilion of the 1964 World's Fair all the same—with the Unisphere, still the symbol of "Peace Through Understanding," out front. The elevated platforms of the former New York State pavilion rise close by. So what if now, after sixty years, an exhibition honors the World's Fair as "A Billion Dollar Dream"? The fair was a titanic undertaking, marred by corruptions, with a cost to the city of at least $60 million. It was the dream of a lifetime for many, but just whom?

The museum is overdue to build an audience, and this could have been the occasion. For opening day, it served Belgian waffles, an attraction of the fair, to all comers. Yet it is still the same low-budget operation struggling for relevance, and it cannot shake off its ambivalence. It serves up neither a celebration nor a critique. It bows to both as best it can, but with a long way to go. For now, too little is left after the waffles have gone.

Speaking of nostalgia, I could never quite love my Walkman. It could not replace my collection of LPs—a sizable shelf apiece for jazz, classical, and rock. It could not match the sound of an LP or even a CD soon to come. But my girlfriend bought it for me, I loved her, and she threw in a tape of the early Beatles, a true game changer in their time but already a distant memory. With its portability, the Walkman promised to be a game changer, too. Who was I to doubt it?

MoMA loves it, too. The 1979 cassette player has entered the collection and now "Pirouette: Turning Points in Design," when nostalgia looked to the future. So why had I forgotten that I ever had one, and how can I fail to name a single other cassette I owned? If this were a turning point, the worm has turned many times before and since. The iPod, too, is gone, and the name of the game is streaming. Before you know it, AI will be telling you what to hear.

Nostalgia for what?

Those too young to remember the 1964 World's Fair can enjoy a model city still on view after sixty years, as if it were made just for them—a literal model city, the fair's scale model of New York. As you search for your block in a half-darkened room, you can feel yourself a part of a more optimistic era. Everyone belongs, it says, but not everyone gets the message. Charisse Pearlina Weston used her 2023 exhibit at the museum to decry the fair as an indulgence, taking over the park from its neighbors. One can feel their isolation, crossing to the museum over an eight-lane highway. One can feel it, too, in an art museum that never has caught on or in the park in winter, all but deserted apart from a brave jogger or two.

Can it recreate the wonder that a child like me once felt? It has maps of almost the entire park, in two and three dimensions, but then there is nowhere to go. Photos show the entrance to an elevated rail snaking through the fair's density of pavilions to the tune of "It's a Small World After All." Here there is only silence. If pavilions for emerging nations stressed local cultures or their entrance to the world stage, one would never know it. The sole local costumes are uniforms for the fair's admissions counter.

It asks to place the fair in its time, but only so far. It was automobile friendly, like Robert Moses, the ruthless urban planner who also organized the fair (a curious omission for the museum), and each of the leading auto makers had a pavilion. So did the ugly temptations of consumer culture and "The American Interior"? Will the show have room for at least a sample of Formica, if not an entire kitchen? Do not get your hopes up. A photo pictures laborers at work, including women, but surely someone had to build all this, and the Fair Pay Act of 1963 did not single out New York.

One can sympathize with the show's ambivalence. The times had all the optimism of a new international order, but all the fears of the Cold War that no amount of show business could dispel. The fair brought with it the hopes of the civil-rights movement, but also protests from the Congress of Racial Equality. The 1939 World's Fair was about the arrival of modernity. That brutal eight-lane highway connecting the city's roads and bridges fell into place just in time. The 1964 World's Fair was about what happens when modernity becomes the norm.

The passage from industrial waste to a park had foundered before. Flushing Meadow was still what F. Scott Fitzgerald called a valley of Ashes" and Robert Caro, in his biography of Moses, "foothills of filth," but change was on its way. Not everyone could afford a car, but the fair fostered them—and automobile culture still rules in the city's white outer-borough neighborhoods. The fair itself attracted far more than wealth as well, like my father and me. A year later, a ticket to the Beatles at nearby Shea Stadium cost just $5.50. I only wish I could have gone.

The fair even had a place for art. Michelangelo's Pietá came all the way from Rome to the Vatican pavilion, although the museum does not deign to mention it . Art is itself about felt experience, not amateur sociology. Maybe a little more such experience could at last put inequality on America's agenda and the museum on a New Yorker's map. The two world's fairs were twenty-five years apart, and none has come since. There is a whole world left to bring alive.

Who took my Walkman?

The questions in "Pirouette" are built into any museum of modern art, not just the oldest and finest. A museum is about remembering, while modern art, consumer culture, and turning points share a desire to make it new. No critic, however visionary, can say just how or what is to come. MoMA includes a 1983 Mac, with Susan Kare's icons for its desktop as a bonus. Surely that if anything was a game changer or was it? It never came close to matching sales for PCs, it leaned heavily on genuine innovations at Xerox, and its white box looks quaint and awkward today.

Still, cool kids loved it, the kind that grew up to become artists and staffers at the Museum of Modern Art. In doing their job as curators, Paola Antonelli with Maya Ellerkmann necessarily exercise their taste in contemporary design. They have to be looking for trends and, with luck, making them. Yet the show has its share of products that are not in the least familiar and do not seem much like turning points. Flasks and carafes from Aldo Bakker, light-weight clothing from Gabriel Fontana, and a faux leather shopping bag from Telfar Clemens look tasteful enough, but they could only wish they had a longer moment in fashion's sun. DJ gear from Virgil Abloh has to appear only because he was last year's cool kid himself before his early death.

Still, cool kids loved it, the kind that grew up to become artists and staffers at the Museum of Modern Art. In doing their job as curators, Paola Antonelli with Maya Ellerkmann necessarily exercise their taste in contemporary design. They have to be looking for trends and, with luck, making them. Yet the show has its share of products that are not in the least familiar and do not seem much like turning points. Flasks and carafes from Aldo Bakker, light-weight clothing from Gabriel Fontana, and a faux leather shopping bag from Telfar Clemens look tasteful enough, but they could only wish they had a longer moment in fashion's sun. DJ gear from Virgil Abloh has to appear only because he was last year's cool kid himself before his early death.

The show's biases are not at all easy to pin down. It cannot get enough chairs—stackable plastic chairs, wheeled office chairs, a flax chair, a soft chair, and a knotted chair. More elegant and better known, Charles and Ray Eames have their low, simple profile for a gentle rocker. MoMA relishes digital typefaces as well, but with a quirky selection. One, it insists, is optimized for optical character recognition, as if your phone cannot recognize practically anything today. Retina, a sans serif font by Tobias Frere-Jones, and Oakland, a more patently pixilated one by Zuzana Licko for Emigre Inc., cannot have changed the game half as much as the base fonts in Microsoft Word. But then, just as compared to the Mac, Microsoft was never cool.

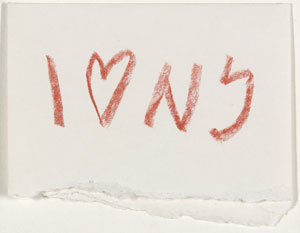

MoMA takes a special interest in signage, like the rainbow flag, the NASA logo, Milton Glaser's I Love New York (with a heart for love), and Shigetaka Kurita's emojis. A wheelchair icon from the Accessible Icon Project (Tim Ferguson Sauder, Brian Glenney, and Sara Hendren) has signaled reserved parking and access for all. One should be grateful for them all. It also demands the digital image of digital reality, however ugly and obscure. Designs by Fernanda Bertini Viégas and Martin Wattenberg track everything from Web search histories to wind patterns crossing the continental United States. Federica Fragapane's plot of "space junk" in orbit, might look at home as the backdrop to a dance club.

Still, there are genuine icons of modern and postmodern life along the way. Some stand out for their modesty and might have been there forever, like Bic pens. There really was a Forrest Mars and not the red planet behind Mars candy like colorful M&Ms. One can forget that the @ sign had a creator, Ray Tomlinson in 1971. Other things caught on without exactly entering common use. Know those small six-sided black and chrome expresso makers that depend on water vapor from boiling on the stove? Alfonso Bialetti adapted restaurant pressurizers to the home, and I could not resist buying it, even if I have practically never used it.

So which is it, museum design, contemporary innovation, or the materials of everyday life? The show includes Swatch, but why not the smart phones and exercise phones of today? It has a 1996 flip phone just when, I should have thought, the future of cell phones was already on its way. A hair dryer, from MüXholos, might have been a turning point back in the 1930s, but it bears no resemblance to hair dryers in salons and bathrooms today. What kept me listening to that crummy Walkman anyway? MoMA needs a better dancer for its long-ago pirouette.

"A Billion Dollar Dream" ran at the Queens Museum through July 13, 2025, "Pirouette" design at The Museum of Modern Art through October 18.