8.19.24 — Thinking in Black

Everything from Adam Pendleton seems to fly by faster than even he can comprehend it, including race. Everything, too, asks you to slow down long enough to ask what you are missing. But then what could oblige you to stop and to think more than abstract art? And I work this in with other recent reviews of the challenges facing abstraction as a longer review and my latest upload.

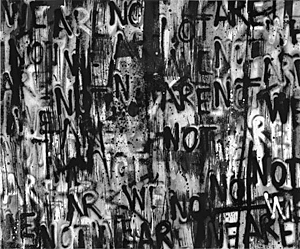

Pendleton is always politically aware, but never in a way that you might expect. He made his name with text paintings, quoting prominent black Americans or simply the word BLACK, like a history of America in graffiti and spray paint. Naturally he covered every inch of the lobby of the New Museum for a show of “Art and Mourning in America,” and naturally it was all but illegible.  Could that make him the natural candidate for a full-bodied abstract art? For MoMA, the graffiti was gone, leaving only a video and a tenement fire escape running the height of the atrium. For the 2022 Whitney Biennial, text and a recognizable image alike vanished.

Could that make him the natural candidate for a full-bodied abstract art? For MoMA, the graffiti was gone, leaving only a video and a tenement fire escape running the height of the atrium. For the 2022 Whitney Biennial, text and a recognizable image alike vanished.

Pendleton is still thinking aloud, with “An Abstraction,” at Pace through just the other day, August 16. The smears remain, but as ghostly compositions. Colors echo the electric tone of black enamel. Diagonal partitions convert a prominent Chelsea gallery into a maze, with repeated warnings not to step too close. The work is coming right at you all the same, stepping into and out of time. Time itself may have tricks up its sleeve when it comes to racism. Pendleton at MoMA also captured the statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond and its fall—and now a Virginia community is returning the names of Confederate leaders to its streets.

Another artist at age forty stakes his career and his sanity on black abstraction as well. And he, too, plays with proximity, distance, and the material reality of paint. Chris Watts may add wood slats to his work, suggesting if only for a moment a view of the stretcher from behind. Other works have dark wood frames and their echoes in brushwork. He adds enough layers of resin that the entirety seems under wraps. Five tall paintings fold into nearly a circle, but with an opening.

Even if you do not or cannot enter, their sheen might have enclosed you this sprig, at Galerie Lelong this spring through May 5. And that sheen is more than half the point. One series incorporates lapis lazuli for its brilliance. Another seems to paint the sky. Watts describes the work as in religious tones, with the precious stone an emblem of the spiritual. Maybe so, but it is painterly and physical.

These days anything can go into a painting, but not everyone is comfortable with “anything goes.” A painter and teacher whom I trust dismissed the show as “student work.” It comes down to a dilemma that I face in review after review here. My heart is still in abstraction, but I still struggle to know what of it is any good. Yet I also argue for proper criticism as about more than judging. Who cares about the “originality of the avant garde” anyway?

The dilemma takes on special urgency for abstract art, which necessarily turns questions of form into questions of value. If a show borrows from past art, is it merely “derivative“? If it does not, how can it foreground the elements of its art? A white artist, Suzanne McClelland has been asking touch questions for years and rewarding them with brushwork and beauty. Her latest, just recently at Marianne Boesky through June 8, made me think of Lee Krasner, with black structuring her colors into something close to tiling. How else could the rich repertory of painting contribute more than a formula or a mess?

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.