In from the Streets

John Haberin New York City

Defacement: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Michael Stewart

Beyond the Streets: Graffiti and Street Art

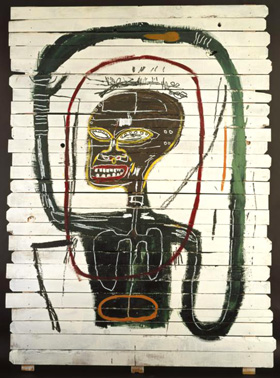

Was Jean-Michel Basquiat a street artist? He drew on street art for his slashing attacks in oil—and he adopted a tag, SAMO, even on canvas. But would he have embraced the label? If you asked him if he painted for the people, he might well have said yes. If you asked if he painted for anything but for fame or for his art, though, he might have said no. For the Guggenheim, he gave voice to the spontaneity and anger of a community, in "Defacement."

In Long Island City, almost directly across from MoMA PS1, a landmark of street art fell victim to the wrecking ball. To add insult to injury, the luxury rental that replaced it adopted its street name, 5Pointz. Just two miles south, though, at the very heart of gentrification, street art has come in off the streets.  A survey of more than forty years fills two huge floors, with glorious views of the Brooklyn waterfront. It has a New York Times review not from an art critic, but from a music critic with a men's shopping column for the Sunday style section. Welcome to Williamsburg with a functioning L train—and to "Beyond the Streets."

A survey of more than forty years fills two huge floors, with glorious views of the Brooklyn waterfront. It has a New York Times review not from an art critic, but from a music critic with a men's shopping column for the Sunday style section. Welcome to Williamsburg with a functioning L train—and to "Beyond the Streets."

But were they street artists?

The Guggenheim bills its show as "the untold story," but does anything remain to be told? Just two blocks north on Museum Mile, the Jewish Museum celebrates Leonard Cohen as an artist, but with concert footage and adoring fans. Even so, it has nothing on Jean-Michel Basquiat. No other painter has achieved such rock-star status, and he burned out like a rock star as well—four month's short of his twenty-eighth birthday, two months than Jimi Hendrix at his death. The Brooklyn Museum had its Basquiat retrospective in 2005, when I expressed as best I could my appreciation and my doubts (so do check out the link). Now a show of just nine works by Basquiat in context of others recovers their shock at the death of Michael Stewart.

Was Stewart himself a graffiti artist? The police descended on him as one, at the First Avenue subway stop in 1983—but that came as a surprise to friends like Keith Haring, with street cred of his own. Stewart studied at Pratt, and the curator, Chaédria LaBouvier, demands to see him instead as an emerging artist in the cauldron of East Village art. A display case has a few modest works on paper with elements of expressionism and all-over abstraction, but not a word, face, or tag in sight. They are also none too promising. They could not save him, though, from death thirteen days later in a hospital, where he entered in a coma and with every mark of police violence.

The outcry that followed has new urgency after Black Lives Matter, and so does the entire show. David Wojnarowicz created a poster while Stewart lay on his deathbed, and the protests only gained in intensity with the officers' trial and acquittal. Lyle Ashton Harris posed a woman in police uniform, to counterpoint the murder by white men. Haring painted the assault with Stewart's neck painfully distended, although otherwise with Haring's insufferable good cheer, and David Hammons represented him as The Man Nobody Killed. Andy Warhol silkscreens tabloid coverage (on a page of mostly advertising), but then the artist of electric chairs knew how to face death. Tony Cokes, who associates East Village artists with gentrification and privilege, this summer at The Shed seems cruel and naive by comparison.

Basquiat was among the first responders. He painted Stewart between two cops poised for a beating, after Wojnarowicz. (The cops switch position compared to the poster, as in a mirror or in printing, so he may have seen a now lost plate.) Yet the victim has become a limp silhouette or shadow. The rest could stand a lot more of that jagged black. A single word above, defacemento, plays on defacement as a synonym for graffiti and the obliteration of a life.

It comes at the back of the show's first room, with more by Basquiat, on the way to a second room for fellow artists and survivors. Only there does wall text introduce Stewart and his death. And indeed the show neatly divides into two concerns. Basquiat dashed off the painting, it turns out, on drywall in Haring's studio, otherwise filled with the marks of others. It owes its blue line to one of them and its composition pretty much to Haring, who cut it out, set it in a gilded frame, and hung it in his bedroom. Basquiat would be surprised to find it in a museum.

It is no big deal apart from its place between his art and the community. It lacks the brutality and authority of his earlier police, an aura that Basquiat envied as much as despised and feared. One painting attests to the Irony of a Negro Policeman. He labeled another La Hara, Nuyorican for the Irish O'Hara, much as defacemento roots his art in the Latin American Lower East Side. He often threw in a copyright mark, as if everything sprang from him, but a text painting lists influences from Leonardo to Malcolm X—some with pride and some forced on a black male by others. If he rises above celebrity and street art to this day, it is through his anger and ambition.

This means business

These days street art means business. "Nobody's ever taught you how to live out on the street," as Bob Dylan sang,"and now you're gonna have to get used to it"—or maybe not. A ticket to the Brooklyn pop-up costs as much as entry to a major art fair, and it ends with quite a gift shop. Within the show, Lisa Kahane wears a t-shirt by Jenny Holzer, and now you can, too. It has protest art from Shepard Fairey and Emory Douglas of the Black Panthers, lots of it, but also posters and souvenirs from Fab 5 Fredie and the Beastie Boys. But then that new building would not have borrowed a nickname from artists if it did not want also to take on its aura.

The irony is all the more telling during a homeless crisis, but could it have been there all along? "Beyond the Streets" begins raucously and innocently enough, with photos of graffiti from the 1970s covering subway cars, freight trains, and gates that descend on closed storefronts. Newspapers document a public outcry, especially in Philadelphia. Before you know it, artists like Barry McGee are creating storefronts of their own, with a mock tattoo parlor, a record store, and shelf upon shelf of spray paint. Led by Roger Gastman, a self-described urban anthropologist, the curators are already turning to music at that, on the cusp between punk and hip-hop. They find quite a scene, in Polaroids by Dash Snow and in photographs of Times Square by Jane Dickson.

![Maya Hayuk's [well, you know what] (Beyond the Streets, 2005) Maya Hayuk's [well, you know what] (Beyond the Streets, 2005)](images/G_I/hayuk.jpg) At last comes art, including a full floor with sections for abstraction and representation. Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring put in a modest appearance (perhaps whatever the curators could round up for sale), while Kenny Scharf has a larger, cheerier, and glibber mural. Mostly, though, the show fast-forwards from the 1980s to the present. It also comes in not just off the streets, but also off the wall. Artists like Jason REVOK and Craig Costello take their black drips into the studio and onto canvas. With Takashi Murakami and the Cowles collection of Japanese art, the trend grows ever more glittery and garish.

At last comes art, including a full floor with sections for abstraction and representation. Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring put in a modest appearance (perhaps whatever the curators could round up for sale), while Kenny Scharf has a larger, cheerier, and glibber mural. Mostly, though, the show fast-forwards from the 1980s to the present. It also comes in not just off the streets, but also off the wall. Artists like Jason REVOK and Craig Costello take their black drips into the studio and onto canvas. With Takashi Murakami and the Cowles collection of Japanese art, the trend grows ever more glittery and garish.

Is it still street art, and how much was it ever? The Guerrila Girls, in their protest against men and money in the arts, make no sense apart from their staged disruptions inside museums. Tags on subway cars might be a kind of text art, but the taggers had more in mind leaving their signature. John Ahearn might be part of the movement, but in lifelike sculpture. Some of the best painting here has little in common with graffiti anyhow, like streaks of color in blackness by Alicia McCarthy, flattened nudes by Richard Colman, and the descending red disks of a sunset in the reeds by Sam Friedman. Still, the curators seem determined to treat street art as not a medium or a practice, but rather as a style.

As a style, its irony becomes still more disturbing. Street art may thrive on its outsider status, but that mirrors the very notion in Modernism of an avant-garde. So does all the macho—the very target of women like the Guerilla Girls. Folk and outsider art, in contrast, cherishes craft and tradition. Conversely, without the questioning spirit of Modernism, the style quickly becomes as tame and repetitive as the worst academic art or second-generation Abstract Expressionism. Murakami has his anime, taggers have much the same curvy font, and those who covered the facade at 5Pointz came off as little more than a single artist.

To add to the irony, "Beyond the Streets" makes its greatest impression when it embraces the contradictions. Set against those wall-to-wall windows, spray paintings by FUTURA2000 and slabs torn from their walls by José Parlá become installations, like a room of artificial flowers by Dabs Myla. A full wall from 2005 by Maya Hayuk looks livelier as one as well, not to mention more of a provocation—a four-letter word that just happens to rhyme with her name. Black silhouettes by Richard Hambleton slip in and out among them all, as elusive shadows. "How does it feel to be without a home, like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone?" Maybe not so bad after all in today's art market, only forget the part about unknown.

"Defacement" ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through November 6, 2019, "Beyond the Streets" at 25 Kent Avenue in Brooklyn through September 29. Related reviews look at Jean-Michel Basquiat in retrospective, Brooklyn street art, and "Grief and Grievance."