We Are Highly Amused

John Haberin New York City

Exposed: The Victorian Nude

Queen Victoria died in January of 1901, near the dawn of a century, the year of a world's fair, and two months after Pablo Picasso first descended upon Paris. The Salon des Refusés had shaken up art there more than thirty-five years before. Yet it took at least a world war, itself over a decade away, to put England's dreams of empire and of art's faded glories to rest.

Then, too, academic art poses as burning a question now as ever before. Only who these days gets to play the academy? A show of the Victorian nude has me asking once again.

After a title like "Exposed," one expects to see through something. Only will one see most deeply into women's clothing, nineteenth-century realism, twentieth-century kitsch, or the Modernism that hoped to displace it all? Well, why not try them all? One can see them all at the Brooklyn Museum, as tawdry and provocative a mix as with "Sensation" three years before. The solemn, silly art may not exactly triumph, but it definitely makes it worth one's while to ask why not. The queen herself would take pride in her lost subjects.

Virtue and bare flesh

One begins at mid-century, on a note of fiendish exaggeration. The discovery, way back in 1506, of Laocoön, the frenetic Roman statuary, had set a challenge to High Renaissance sculpture and an inspiration to Mannerism. In the same way, poses out of Roman models by Frederic Leighton dared painting and sculpture to master as tortured and torturous an anatomy.

Next comes a long, central room, divided into themes that one forgets within minutes of leaving Brooklyn. It mixes portraiture and an almost endless stream of scenes from Greek myth, harems, and early Christianity. Again a little torture and suffering go a long way to expose virtue and bare flesh.

The show continues through World War I, as if daring one to call a new century modern. Walter Richard Sickert, John Singer Sargent, and Gwen John still pack a bit of a wallop with their unkempt lighting, frank portraits, and frankly casual nudes. Johns's woman, feet firmly on the ground, stares directly at the viewer, without even bothering to tidy up her studio. Already, in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Picasso had made that confrontation into a frightening shake-up of reality. However, Johns stares back confidently as the artist herself.

On the way out one has a surprise, too, not just photography but pornography, including particularly funny short subjects. The jerkiness of the early medium seems designed to make the act of undressing less into a peep show than into a silent comedy. If porn must pick on women, one wishes that men today—or the movies, for that matter—did it half so nonviolently.

But the modernists one never does see have the last word. They had better, compared to such nonentities as William Orpen, William Etty, or (gulp) Herbert Schmalz. One starts to worry about Britain's peculiar obsession with heavily decorated interiors—with the nude as the greatest decoration of all. Can that be all there is, one starts to wonder, to Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, or Leon Kossoff as well?

They may not make an appearance to argue back, but Classicists and Pre-Raphaelites do, and it hardly helps. Such famous names as Edward Burne-Jones look less compelling amid all this mildly risqué calendar art. Those who call British art an oxymoron will not be convinced.

Did I see this before?

The Victorian era still stands for prudishness and repression, but the Victorian nude should come as no surprise. Sure the period gawked. It invented the very word pornography, and it saw no reason to disentangle art from spectacle. Galleries may thrive now on "sensation," but the nineteenth-century drew big crowds to magic acts and carnivals. Lewis Carroll's photos of young girls, also included, still disturb and perplex, but he managed to get parental permission for them all.

Even without Michel Foucault, the philosopher and historian who charted a History of Sexuality, one knows that sexuality has a history, and that history is ours as well. The nineteenth century all but patented art for a broad public, as well as a new feminine ideal. Women not only had to stand on pedestals, but they had to slim down first. Even the rebels back then, from Gustave Courbet with his lumpy young women to Thomas Eakins with his muscular nude photographs and Alice Austen with her lesbian art and love, play against an older sensibility. No wonder "Exposed" feels familiar—if less like stag films now, perhaps, then like women's magazines and television.

Art fans will feel even less surprise. One knows the traditional training in life drawing. One recognizes the high moral narratives and exposed breasts from the Pennsylvania Academy and the French Salon. Some demands for censorship, the curators argue, even arose from fear of a French influence. Still, if Gay Paree had a darker attitude to sex, not to mention better food, the Victorian nude hangs on display in England pretty much any day. Most works come from Tate Britain or, appropriately enough, the Victoria & Albert. The rest draw largely on regional museums, where they may well take pride of place.

Conversely, the show fails to articulate just how it all differed from French and American drivel in the legacy of Romanticism. One has a hint, perhaps, in the elaborate costumes, Moorish scenes, and fascination with the spread of Christianity among the pagans. One remembers that the British held an empire such as France had nearly lost. America's west still stood more as a promise and a challenge. Still, the show has no interest in antecedent gawkers or moralists. The period, for all one knows, springs from the head of Leighton and the queen, fully overblown.

So exactly what makes the Victorian nude unique? What makes this whole exhibition more than self-promotion for Tate Britain, one more institutional power play in the postmodern art world? By implication, what was so special about the art that was about to make it all but irrelevant? The show's virtue lies in asking exactly that. Sure, a critic or two will marvel at finding less repression than they expected of Victorians. Sigmund Freud had to know better, and so indeed did Lucian Freud and Bacon, as they added their brutal sensibility.

Rather, the show thrives on the same things as pornography or gross-out humor even now—familiarity and repression. It gets one asking what repression then meant and why it still feels so familiar. Just as Foucault charted a history of sexuality, one can ask better now for a history of pre-Modernism. Yes, it milked the nude even while censoring nudity, but how? In the tradition of post-structuralists like Foucault, let me ask not for a simple ideology, but for the very terms of the debate.

The gloves are off

What could be simpler than the nude? Take off all your clothing, look in the mirror, and decide for yourself. Without fashion or fabric, you put on display something as solid as flesh and as bold a threat to Victorian propriety. Or do you? In fact, nudity then and now never comes without the most fashionable of beliefs, and yet those beliefs never look single or simple. The gloves are off, and the Victorian nude embodies some remarkable contrasts.

For an empire, it came literally in black and white, male and female, Christian and Pagan. It could be The Greek Slave of Hiram Powers, her western virtue tested by the Turks. It could be Philip Hermogenes Calderon's Saint Elizabeth in her Great Act of Renunciation, shedding clothes along with her worldly commitments. The Classical era holds out art's ideal, or it predates Jesus and then martyrs Christians.

The nude evokes a classical era, a remote past and a lost empire, but also presence and immediacy. It stands for a training that still defined artistic tradition. Conversely, it evokes the promise of realism in the hands of an authentic genius. It offers scenes of the model in the studio, emblem of art's cool eye in search of perfection—and hands-off respect for a woman's virtue. Conversely, it puts nothing in the way of fulfillment. No wonder the theme of Pygmalion grew so popular that Burne-Jones turned out a whole series of it.

Nudity stands for art's ideals or its strict adherence to the natural, for purity or for sex, for art's delight in the senses or mere sensual delectation. It could mean unspoiled or barbaric. Anna Lee Merritt's Love Locked Out offers a boy desperate to reunite with his father. Herbert Draper's doting nudes suggest quite another kind of desperation, as they fondle a dead Icarus. Indeed, just as women in this solemn tale fall easily into desiring, women paint like Victorians, too. As with Merritt, I could not see much difference between male and female artists until I came to Johns.

The nude stands for the ambivalence of art or nature—each both ideal and natural, formal and narrative. Nature enters as a garden from which fallen humankind has long since separated, a passive world that human nature can only despoil. Or nature sneaks in violently, like the snake that wraps around Evelyn De Morgan's heroine in pursuit of pleasure. Arthur Hacker's The Cloud catches a very adult nude in the violent embrace of nature itself.

The oppositions could exist in a single painting. One harem scene throws together white women quailing in fear, black women strutting their stuff, and Arab men flaunting their lechery and power. William Scott's nude holds a jug and flowers, signs at once of innocence and sexual experience. Her jug bears water's purity, but also an opening and a font. The whitest of flowers recall fertility and growth. In every baring of the flesh, the Victorians risk double exposure, but they delight in a single vision of moral perfection.

The eye of the beholder

In each of these contrasts, the Victorian nude stands for the ultimate of purity and of sin—and as itself the ultimate test of virtue. The test calls for an art of revelation, an art true to nature. Yet it sees revelation and nature as contested, with the nude as battleground. As others have put it, the nudes function as "idols of perversity." Most remarkably of all, painting does not just carry moral lessons for the viewer. Rather, art and its subject had better behave, while artist and viewer stand apart as judge and jury.

In other words, the nude asserts the primacy of the visual. Facing the nude, one knows to look and not to touch. Seeing life, the artist must master illusion. Confronted with the illusion of the nude, one looks safely, knowing that one has the moral well in hand. The nude puts art to the test, but the eye looks on, central and uncontested. It claims to have nothing to hide.

Michael Fried called the concept theater, but the provocation could take place backstage. Charles Hazlewood Shannon gives us Venus with a concave mirror. The age-old subject looks back to a legendary classical Venus and its temptations. One may share the temptation, but from outside. No one invites the viewer to enter as in Picasso's brothel. Venus never looks one in the eye like Johns. Beauty and truth remain, literally, in the eye of the beholder.

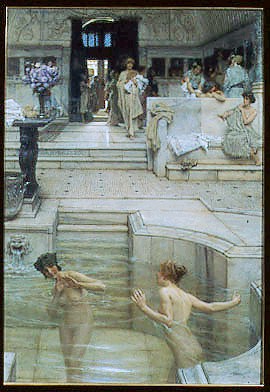

In style quite as much as subject, the nude must perform for the eye and no other human sense—the unblinking eye of the connoisseur. Where painting of the Renaissance took sculpture as its model, this dull style shuns tactility. Artists knew perspective cold, and their surfaces look cold as well. In Lawrence Alma-Tadema's bath, the water's surface gleams, but backgrounds blend together. Shadows outline the muscles on a woman's behind, but like a painterly exercise, and she still blends into the scenery. As I turned to walk away, as a male in New York, women fully clothed took on an astonishing locus of desire.

The Victorian era offers skill and tidy morals, but not without some nasty contradictions. One has boring art and inadvertent comedy, the scandals of gender and empire, and the problems never fully erased in presenting the nude and all its contrasting terms. Among the nudes, as desired and desirers, one has plenty of stand-ins for the viewer's erotic gaze—what Mieke Bal calls "focalizers." Yet paradoxically, the emphasis lies in the viewer's judgment, a judgment that can always turn back through the stand-ins on the viewer as well. Ironically, Bal calls her own book Double Exposure.

This art has an impossible task—to suspend and to affirm both pleasure and judgment. It persists in the fragile pretence of both pleasure and purity, the boast that when the heroine falls, we are not amused. It makes the nude untouchable, part of the two-dimensional surface, but a decorative surface itself never loses its sensual overtones. Edwin Long offers a parable about Helen of Troy. To describe her perfection, a painter can chose no living, imperfect model, so he must combine features from five different women. Yet to tell his story, Long's own art shows not an ideal after all but all five, with all their—and his own—very human limitations.

Surrounded

The twentieth century breaks so decisively because its rebellion never amounts simply to letting go. Modernism clings to repression and judgment, but in order to foreground them, to toss them right back at the viewer. In place of Venus's indirection by a mirror, one has Marcel Duchamp's forthright peep show or the gloriously palpable mess of Cubist space.

Only is that enough? "Exposed" has such currency because it reflects on the debates and, frankly, hypocrisy today. Is Modernism really dead? The Victorians have me asking once more, knowing that I might find it easier to say if I could finally pin down the object of its rebellion. If conflicting narratives drove the Victorian nude, just think of the narratives now.

Modernism speaks forthrightly about sex and the divided unconscious. Art today returns to kitsch, puffing up simple-minded work with endless theory. Or Modernism confuses white, male lust with universal experience, while art today creates forthright views of gender and cultures. Modernism still reflects on beauty and form. Art today, especially those Brits, settles for shock and sensation. Or Modernism escapes into abstraction, while art today treats abstraction as just one more special effect amid the lived, the pleasurable, the experienced, and the seen.

Modernism cuts right through the whole idea of fine art. Art today settles for money. Or Modernism may park itself in Queens for a year or two, but only to build big museum institutions—with luxury housing attached. Art today makes going beyond the big money of Manhattan, for Brooklyn and beyond, the only way to go. The whole argument keeps both sides alive, assuming Postmodernism has much of anything new to say. Or Modernism only seems alive, as art pulls off some wicked speeches at its perpetual wake.

So now, yet again, the Brooklyn Museum challenges Modernism with almost a parody of old-fashioned realism and a chance to argue. One comically poor work follows another, wrapped up in cheap shocks and pathetically sincere assumptions about women and the course of empire. Bad art comes in the service of a museum's vision, and an intelligent one at that, just as when the Jewish Museum questioned art about the Holocaust. One may still be shaking one's head as one turns, barely a few rooms away, to the valuable replay right now of Judy Chicago and The Dinner Party from the late 1970s.

Only one tiny thing: this time, I am not talking about Postmodernism—or am I? It all dates back to good old Victorian England. If you call yourself a modernist, with or without the post, "Exposed" has got you surrounded.

"Exposed: The Victorian Nude" ran through January 5, 2003, at The Brooklyn Museum of Art.