Art As Information Science

John Haberin New York City

Gary Hill at the Guggenheim Soho

What do you want?—Information! Those threatening words from the '60s rang out again in the summer of 1995, at New York's Museum of Broadcasting. They opened six daring episodes of televised kitsch, The Prisoner. I remember well how they once terrified me. Back then, the prisoner could hope only to escape. If he heard the same words now, he would go into multimedia.

Today one tends to think of books, or art works, as information in a solid container. Then throw away the container. Sure, the press always finds someone quaint enough to defend the feel of leather binding.  Yet it does nothing to spoil the formula: content plus form, 0 to 60 in record time plus sumptuous upholstery.

Yet it does nothing to spoil the formula: content plus form, 0 to 60 in record time plus sumptuous upholstery.

One might expect video art to confirm the information metaphor. In one history, video derives, after all, from a particularly numbing form of communication, commercial television, the subject of MoMA's "Signals." It reduces content to a fixed sequence of pixels. The image's form, a mere pattern of light and sound, only appears to lie within the monitor's nearly flat surface. There is literally no there there.

Instead, video is happily turning the metaphor inside out. Gary Hill's solo show at the Guggenheim Soho makes a particularly intriguing exit from the information superhighway. Nobody can drive in New York City anyhow.

The virtual art object

The information metaphor never really worked for society either. Consider what really happens as new media for consumers replace books. I should know: I develop them both for a living.

CD-ROMs can hardly be dog-eared and discarded. They can be carried to the beach or to bed, but at a price. Their constraints make them more obviously physical objects than ever.

They depend on fewer, more costly outlets owned by larger corporations. In this, they accelerate market changes that affect book buyers too. Yes, a small elite that cherishes a private library of first editions loses out. So do the masses who think of books as a nearly endless choice of inexpensive objects. And they force viewers to confront that old disparity between words and images. Along the way, they stimulate some of the shocks and emotions that never did resemble information.

Recent video enacts the same trends on the cheap. It reflects on the stubborn perplexity of form and its conventions. Perhaps early video art recalled sculpture, like the stacks of televisions by Nam June Paik. Or perhaps it documented performance art, like Joan Jonas or Bruce Nauman in his ironic ten-minute tirades. These early installations look made from used parts.

Newer video artists, like Hill or Bill Viola, create a polished installation with no fixed duration, a kind of ensemble piece for tubes, wiring, and dim walls. One stumbles to locate or define the image and the work. One cannot overlook the art object—or the museum institution for which it is designed.

Stumbling in the dark

All but one of Hill's ten installations downtown date from the '90s, although he was born in 1951. He gives each work its own space, as if it were planned from the first for a darkened room alone in a major museum. We get not a retrospective, but an artist's statement. Hill is fascinated with how images come to be—and come to mean. He succeeded in getting this visitor to share his fascination, to marvel at it, and to question my own fascination.

In one large rectangular room a cylindrical projector hovers suspended at eye level, like a huge, sleek cigar or tiny spaceship. One must walk around it, if only to reach the far door and escape. By that time, one perceives that it is rotating, slowly distorting a projected circle of light into an oval. As the circle re-forms, so does the image. One perceives its steadiness and its transience, however, more than its sense. I neglected even to write down what one sees—a child's face. Her eyes, one's own, and the beam of light could each be viewer or object.

The soundtrack holds text from Maurice Blanchot's The Gaze of Orpheus. Its title could amount to yet another metaphor for viewing—or a fixed point of reference for each view. As a literal fragment, it could stand for the fragmentary image and the visitor's disjointed perceptions.

Indeed, I just spotted a fellow museum-goer, a child, before stepping on her. She lay still, arms to each side, as if taking on the shape of the machine and its relaxed rhythm. The artist, the device, the light, and I each had to make sense of things in our own way. And those "things" included all the images, objects, spaces, and people among us.

Sometimes the visitor is the disturber of sense as well. Penetrating fearfully into an unlit room, one slowly comes to admire seven small screens of various sizes, their innards and hook-up visible. They drop from above, like delicate black spiders or enormous pendulums, casting their images on books strewn below. Leaning to discover the projected faces and to read the text, one naturally starts the pendulum swinging, sometimes on purpose. I had rarely seen art so aware of the monitor—or the printed page—as physical presence.

In another room five monitors display the head, hands, and feet of someone exploring a forest. The five squares themselves outline a man, but the extremities move as if each possessed of an independent mind. They seem closer to the leaves than to each other. The walking man opens the show and dates from a decade ago. Hill's themes have been constant since then. For him, meaning and personhood are always about to escape together for a walk in the woods. They just have to run into the walls of a carefully crafted gallery first.

Virtual languages of art

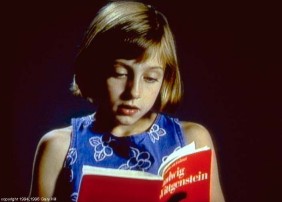

Hill's images in fact mostly contain people or words. He associates both subjects with consciousness that another being can never capture. On one huge screen, a young girl reads Ludwig Wittgenstein's Remarks on Color. To the philosopher's epic perplexity over the gap between meaning and reference, she adds her innocent gestures and mispronunciations. As always, Hill's installation throws the visitor into much the same morass with the actor. The large, open room resembles a lecture hall, with a teacher that one wants to correct and yet cannot quite understand.

Hill's favorite texts share his obsession with identity and unmeaning. Several works cite Blanchot, perhaps the least-known existentialist. The French writer so purified his language and plots that he became something of a role model for postmodern novelists. In Thomas the Obscure, for example, the hero takes a few steps into the ocean, confronts the senselessness of his action, and turns back. That is about it.

When I first read Blanchot, I hardly knew whether to admire his incredible self-control or share in his wry despair at existence. I was unsure whether to laugh with his identity crisis or at it. I felt much the same when I first discovered Hill, even as I drew amazement from his combination of art and a medium so simple as a book. I was wrong, dead wrong. The Guggenheim's writings contributed, no doubt, to my reluctance to take Hill as seriously as he deserves. They manage to overlook anything but the grandeur of his ineffable sensations.

The child reading modern philosophy is really funny, but should one notice? Those five spread-eagled monitors suggest a crucifixion, but is Gary Hilld making fun of art's heroic pretensions or reveling in them? The lack of resolution says a lot about Hill's strength and weakness, as I felt them during my visit, before I came to understand his challenges to my very certainty and his stunning virtuosity. These videos are precise and unsettled enough to lead one through some of the blackest rooms of a museum—or of life. They also come very close (or so I felt at first) to toying with ideas, which one can pick and choose like overwrought hors d'oeuvres.

You should see how much my view of Hill was to change, how much I came to enter personally into his work. Had he improved so much, or had I? A reader should always doubt first the critic. Yet to return where I begin, information is a dangerous paradox—a metaphor that denies the importance of form. Its denial is what makes it loaded as ideology. Perhaps, I wondered, Hill was similarly trapped in the sublime. In the hands of another, less-uncompromising artist, his juxtaposition of meanings could easily have become too easy a metaphor for nonmeaning. But then a metaphor itself implies meaning, and the puzzles in his art continue to reward the puzzled.

I accepted the invitation to compare phenomena with language. I relished the chance to feel for myself and outside myself. I found a variety in the ten rooms that I can only have hinted at here. Like the woman on the floor, I nestled into the quiet. Yet I also wondered if I were not insulated from real experience by the darkness. What makes Hill so remarkable is that the answer may always be no.

Gary Hill's work ran through August 20, 1995, at The Guggenheim Museum Soho. My sincere thanks for the image to Dave Jones Design; Jones has assisted Hill on several such dazzling projects, and his Web page also includes video clips of the installations. The choice of a stammering child, like the changes visible in this review, reflects my own growth in appreciation of Hill's work only later. I can only add that my appreciation grows with every new work.