Method in His Madness

John Haberin New York City

El Greco: A Retrospective

One approaches a blockbuster expecting the sensual overload. Strong, careful lighting lead one on. Labels next to each painting further the drumbeat of praise. The crowd, caught up in the work or just hoping to get close enough to see it, comes close to drowning it out. Quotes from artists and critics, stenciled high above on the museum walls, exemplifies its majesty.

What does that mean for El Greco? One can ask where he lies between majesty and eccentricity. Related reviews look in depth at just a few key paintings, his years in Toledo, and his roots in Crete.

Variations on a theme

El Greco's retrospective comes with plenty of help. I should have come better prepared for the onslaught. I should have dressed like Uma Thurman, in athletic gear and carrying a long sword. It would go with the artist's transformation of Toledo into a fantasy world, its towers and hills as monuments to religious fervor.

This once, though, I had a fantasy of my own. Suppose that night had fallen. Suppose that the crowds had gone home, the lights had gone out, and only I remained. These paintings look like they could glow in the dark. But why?

Like his leaps in space and exaggerated gestures, El Greco's electric color helps to define his otherworldly aura. In popular culture, it has made him the Vincent van Gogh of the Renaissance. Like the Dutch artist working in France or, later, Pablo Picasso, he suggests an archetype of the avant-garde, the radical outsider.

Born Domenikos Theotokopoulos in Crete, he continued to sign his paintings in lowercase Greek letters. One might almost think that his art brought forth New Testament in its original language. Perhaps his patrons in Italy and Spain felt that way, too. No wonder Giulio Clovio, who would later support Bartholomeus Spranger as well, told him to seek his fortune further afield.

Yet his light also made me attend more closely to three apparently sober and less familiar works. These variations on a theme hang early in the exhibition. In each, a boy blows on an ember to keep it alive, so that he can light a candle.

For once, the artist focuses on an undistinguished person. For once, he selects a passing incident, a dark chamber, and a familiar source of light. Yet the boy got me thinking harder about the white that penetrates El Greco's figures and disrupts the sky. It got me seeing an artist whose obsession with the limits of expression makes no sense apart from the limits of his time—and the limits of my own.

Gaining ground

Although atypical in subject, the paintings typify El Greco's ambition. For starters, the artist is determined to master nature, starting with the first version early in his career, perhaps before his departure from his second home in Venice for Spain, in 1577. In the last two versions, a monkey and an older man flank the boy. With each fresh attempt, the figures gain in solidity and integrate more firmly into the surrounding darkness. By the last, in the 1590s, the texture of the man's beard contrasts subtly with the monkey's fur and the boy's smooth skin.

The boy and his strange friends look only at the candle. The monkey's winning smile contrasts with the older man's crooked teeth. Together, they blur the distinction between human and inhuman, between sanity and madness. Yet their intent gaze and tight circle, establish an intimacy with the viewer, like an act of communion. Each viewer must enter the same human madhouse. For El Greco, matters of life and death arise from an entire painting, the entire world, and their attendant light, not from a handful of madmen.

The artist may have come from a "backward" island on the edge of the Venetian empire. Still, without question, the boy and his ember place El Greco on the cutting edge. Genre painting was just emerging, as was sympathy for peasants, children, and animals. Also in the mid-1570s, while El Greco lived in Venice, Paolo Veronese created a scandal with just that. The Inquisition put Veronese on trial for papering Feast in the House of Levi with "buffoons, drunkards, dwarfs, Germans, and similar vulgarities"—among them a stray animal conspicuously in the foreground. After a trip to Italy of his own, Hendrick Goltzius portrays a monkey as a captive but independent mind.

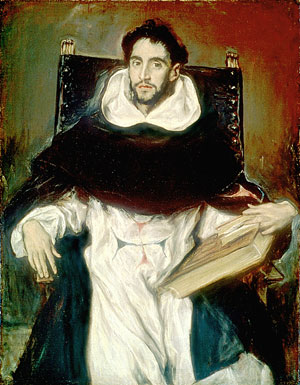

Conversely, while struggling to keep up, El Greco imitates a lost painting from Classical times. In a period of religious and artistic struggle, he asserts the Renaissance ideal of artistic and intellectual revival. His known comments on art display a studied elitism. In a memorable portrait, a cleric wields two books with the spread fingers of one hand. A patron of the artist's and a friend, he does not even worry about losing his place. This painter prefers the company of intellect and power.

If El Greco never forgets an artist, past or present, he also seems never to forget a motif of his own. In those three versions over twenty years, he develops variations as if he had been contemplating his portfolio every day. Today, he would be pushing it all on CD-ROM. Call it an obsession, perhaps indeed a bit like neurosis. Then again, call it the work of a painter determined to succeed.

In short, even El Greco's brief venture into caricature leaves one aware of an astute, mainstream artist. One can see why he began painting by icons, for the market in Crete, and the Met includes one that, after cleaning, shows his signature. One can see why he then took on the artistic capitals of Italy and Spain. One appreciates his disappointment in leaving first Venice, then Madrid and the court of Philip II. One appreciates all the more his acceptance in Toledo. If this be madness, there is method in it.

The Mannerist and the modernist

Over two years ago, the Frick Collection exhibited just two of El Greco's motifs and just seven works. It provided insights into his obsessions and his growth. It let one study his career, in particular its relationship to Mannerism. One better understood a period haunted by political and religious conflict, a growing private market, copies of the past, and unstable meanings. One got a sense of his involvement in Counter-Reformation ideology, but also his turning the tables on any easy idea of black and white.

A large retrospective will not help me say all that better, but it projects all those themes intelligently onto the course of a rocky career. Art historians like to point to El Greco's uneven quality. He evolved slowly, and he died in 1614 leaving a notoriously dull workshop, including his son. Fans, in turn, take every deviation from the norm as an emotional revelation. The Met's thoughtful selection navigates the shoals of his reputation, and he looks as pressing as ever.

The Met charts both chronology and stability. One may look back in amazement at the progress from eastern icons and cluttered compositions to the intensity of the final room. With an Adoration of the Shepherds, set at night, light from the infant Jesus floods the earth and sky, making a human fire quite superfluous. The skillfully foreshortened bodies, distended just past the natural, make up a spiral encompassing the clouds. In effect, they compose an actual stairway to heaven.

Along the way, the museum pauses to hang those three variations on a theme side by side. Later on, a full room isolates portraits. In these secular themes, one notices a greater restraint in the handling of white. Their somber expressions and neutral backgrounds were to influence Diego Velázquez and Velázquez portraits (or attributions to Velázquez) in the next century.

The retrospective claims the artist for his own time, an argument that has unsettled the history of other Mannerists, such as Parmigianino, as well. It does not even address directly the popular myths of his madness or lousy eyesight. Indeed, I wish that I could see as clearly. It does, however, acknowledge his rediscovery and influence on modern art. Wall labels do not bother reproducing works from which he borrowed. They instead show drawings after El Greco by Jackson Pollock, Franz Marc, and others not all that crazy either.

Thus far, I have taken three rare paintings, all out of the ordinary. One can see the same mainstream aspirations throughout the Met. It restores El Greco's light to this world. Take each of the lessons of those three paintings.

The naturalist and the professional

The progressive naturalism of the boy and his ember continues through El Greco's life. One talks of his art as ecstatic, but he will not always show even Saint Francis in ecstasy. The saint's arms, crossed in contemplation, play down the stigmata on his palms. No wonder people attribute El Greco's distortion to astigmatism. Seriously, the modest colors and textures in Francis's cloak enhance the sheen and solidity of the skull in front of him. Elsewhere, in a single painting, the artist can command his eerie light to illuminate a face or to impart texture and opacity to a veil.

His career, too, shows that direct appeal to the viewer, with elements that thrust out of the picture plane. Somber clouds behind a Crucifixion make the cross beam into the leading edge of an airplane wing. In Ecce Homo, Jesus looks up and outward, while the heavy wood of the cross angles outward as well, palpably toward the viewer.

His career also shows his voracious appetite for artistic models, including in his approach to light. In icons back home, whether he created them or not, he saw white highlights rather than shadow used to model drapery. In Leonardo and Titian, he saw light that diffuses beyond an obvious source, appearing to arise at once from the sky and from flesh. In Michelangelo and Jacopo Bassano, a likely source of the boy, he saw how natural light creates form and motion. In Tintoretto or the acrid colors of Flemish Mannerism, he saw daylight and household fires as white as lightning.

Regardless of the sometimes greater depth and subtlety of his influences, he had no qualms about competing with them. In other Mannerists, he saw leaps in perspective much like his own. He saw isolated, apparently secular figures smack in the middle of religious narrative. Approaching 1600, he saw a growing movement toward the personal and immediate, and he ran with it. In his last years, El Greco again invites one into a closed circle. In a Nativity, figures looks down and strictly within the scene, with an intimate grandeur approaching the Baroque's first generation.

His career also shows his compulsive return to his own ideas. In two paintings here, from the four in the Frick's exhibition, he restages the cleansing of the Temple decade after decade. Each time, he repeats much the same composition, with the same perplexing serving woman ignoring the whole thing. Each time, too, he makes the anatomy more convincing and the architecture more unified.

Okay, if everything looks so normal, why does it also glow in the dark? What happened to the idea of the normal anyway? I may have left that boy and his friends too soon.

The visionary and the vision

Light and fire have long had powerful associations with life—whether natural or supernatural, human sustenance or divine punishment. Vision has the same ambivalence toward the visionary. With Mannerism, notably with Michelangelo's late work, Neoplatonism made all this common currency. El Greco pushes these associations to their limits, in the service of the church and king. That goes without saying. He makes one reimagine the limits, too, until one feels them as modern.

Better get the platitudes out of the way first. In myth, it took the gift of fire to set humans apart from beasts. In Protagoras, Plato has Prometheus bring "a most dazzling fire" only as a last resort, "at a loss to provide any means of salvation for man." In myth, too, however, fire comes as a dangerous theft from the gods, and in Plato's Philebus a "godly fire" brings forms of wisdom.

The boy burnishes an ember as a chore and a delight, to keep it and himself alive. Yet the monkey shares in its command, and the older man looks reduced to his animal nature. The human presumption to control the spark of life comes close to idolatry, and it upsets any natural distinctions between real and imagined, sinned against and sinning. The three gather round the flame with a terrifying fascination. They could stand for a dark parody of the three ages of man, and they implicate every viewer in their vicious circle.

Throughout his career, El Greco's light functions at once as a natural source and a divine spark, at once the reality of the flesh and its dissolution, at once the perception of space and the perception of God. It calls one to identify with both the savior and the fallen. For El Greco and Mannerism, the vulnerability of insight may well come with art itself. In their craft and the obsessive quoting of the past, a striving for moral clarity makes fate all that much more uncertain. With each return to the boy, El Greco's command of light improves, and each time the monkey becomes more of an equal partner.

Ordinary people get their due, drawn toward God while also, sometimes horrifyingly, tempted by the godhead. In an early Last Judgment, the fires of hell take up only a small corner, like a primitive cave within the painting. However, their orange light dominates the whole. In an Apocalypse completed the year of El Greco's death, anonymous men and woman command the center of John's vision, with the purity and dignity of their nakedness. Yet in a Lacoön, the serpent tumbles the visionary into the viewer's space for his presumption.

The treachery of judgment makes the images of contemplation that much more poignant. It also underscores the heartfelt humility of his last and greatest works. In that Adoration of the Shepherds, a shepherd already stands head and shoulders above the others. One wonders only slowly how he can deserve to link even Mary and Jesus to the angels above. One notices even later how he stands so high—not floating, but because both feet rest on a foreground rock. I thought of the Church upon Saint Peter. Light and form gain in clarity, but the distinction between reality and metaphor dissolves for good.

El Greco's retrospective ran through January 11, 2004, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Related reviews look at "El Greco: Themes and Variations" at the Frick in 2001, his years in Toledo, and his roots in Crete.