Born Again

John Haberin New York City

Joan Miró: Birth of the World

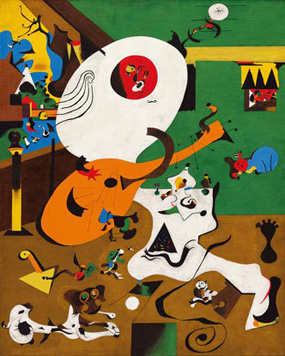

Miró's Dutch Interiors

Joan Miró once described his Birth of the World as "a sort of genesis," and the claim makes sense—but then so does its hesitancy about that one special breakthrough. The Museum of Modern Art borrows its title for a display of sixty paintings and ever so much more from its abundant collection. It shows an artist playing with idea of origins, for art or the world, while being born and born again.

Miró painted Birth of the World in late summer or early fall of 1925, at his family's farm in Montroig, in Catalonia, which he still called home. MoMA gives it pride of place with a lengthy description outside the show's entrance, and it does feel like a rebirth. So many worlds emerge from its novel mix of poured, brushed, and flung paint on partly unprimed canvas, for an unprecedented subtlety and mystery.  Yet it comes well into the show, from an artist who kept reinventing himself. What, then, makes it so clearly his, and where should anyone begin? As a postscript, Miró often worked in series, and his Dutch Interior at MoMA was only the first of more to come.

Yet it comes well into the show, from an artist who kept reinventing himself. What, then, makes it so clearly his, and where should anyone begin? As a postscript, Miró often worked in series, and his Dutch Interior at MoMA was only the first of more to come.

Eight years ago, the Met paired photographs of Dutch art with his paintings to show the correspondences. It numbered every element as in a puzzle to connect the dots, and the numbers run into the dozens. Things are more or less in place, down to a dog and cat on the floor and a shelf and painting on the wall. They have merely run wild. The peaceful city out the window in Hendrick Sorgh's Lute Player now bustles with life down to people boating or drowning in the canals, a gable has become a pedestal with a very suspicious sculpture on top, the lute has taken on comic proportions, and so has the dog's anus. People and pets multiply into a bat, a spider, and footprints flying every which way, much like Miró's art.

A fresh start?

Barely a decade ago, the museum looked in depth at just ten years, starting in 1927, as "Painting and Anti-Painting." (I dived at length into the "anti" part then, so do check out the link just now.) Now it spans much of Miró's career—from even before his first trip to Paris in 1920 through his largest work yet, a mural for Harvard University's graduate center in 1951. MoMA snagged the canvas after it, too, had a rebirth, in tile. Now the emphasis is most definitely on painting. Even the death of the Spanish Republic, which obliged a return to France, and the Nazi occupation, which drove him once again from Paris, became opportunities for rebirth.

At the show's end, he had more than thirty years to go before his death in 1983, at age ninety. One can, though, go far by wrestling with that one gray painting. It turns stunningly from some of Miró's sharpest colors just two years before—or did it? He had already shifted to near monochrome and introduced gradations, with the sepia tones of The Family in 1924. If anything, he now adds white and red highlights for two of his newborn worlds. And a green sky and yellow ground are back by year's end, along with more shards of white and red.

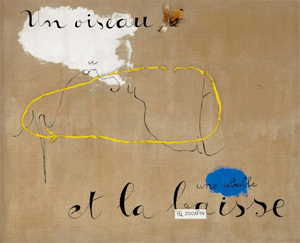

Birth of the World also depends on spare but intricate calligraphy. Yet it had already taken flight in The Family, where sperm morphs casually into spores. Later, clusters of short curves will serve at once for mountains, sea crests, or birds. Text can enter as well, if only one can read can read it. It might be the elegant cursive at the lower right in The Hunter (Catalan Landscape) in 1923, like an artist's signature, but with only the cryptic said—perhaps part of the Spanish for remnant or reminder. It might be the later poetry of Hirondelle Amour, or the twin grace of a swallow and love.

Miró is always cleaning house and then complicating things once again. He also makes it hard to know where the simplification ends and the complications begin. There is no telling, too, where drawing ends and where writing or painting begins. Tragedy turns abruptly into comedy, lyricism into sobriety, and figure into ground. In each case, the alternation speaks of germs and germination, flight and love. They are all signs of another birth, but something must die so that something else can be born.

Like Modernism, Miró insists on reinvention and a fresh start. As with Modernism, too, neither is possible apart from a close scrutiny of art and its past. He revisits art history, with the pleasure, mockery, and transformations of his Dutch Interior in 1928. They put him front and center in Surrealism, but without the literalism of Salvador Dalí or the obvious mind games of René Magritte. He also anticipates more than any other European modernist the postwar eruption with Abstraction Expressionism in New York. His sign systems and stains will have a rebirth of their own with Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

His reinventions found him champions in Paris, but they kept him apart in Spain. A chronological layout tracks his movements, but it all but begs visitors to circulate freely. A corridor between its two rooms holds artist books, with Miró's illustrations of modern poetry—but then titles like Acrobats in the Night Garden or Person Throwing a Stone at a Bird have a poetry of their own. And their hand lettering recalls the text in his paintings. The show ends with poster and catalog cover designs for a retrospective in 1953. Speaking of new beginnings, MoMA has been here before.

The Catalan in exile

Miró stood apart even in France. A still life from 1921 has Le Journal, the newspaper, on a table top tilted into the picture plane, just as in Cubism. Yet it also bears the artist's portfolio, glove, and cane, and the letters Le Jo, the museum argues, may belong to the Spanish for far away. He is too elegant for a Parisian garret and too eager to return home. Once he does, he makes his first simplification, with more muted colors and bare outlines that may belong to a table, its shadow, the light from a window, or the cryptic signs yet to come. A sprig of wheat also introduces organic imagery right alongside the inert forms of a coffeepot and strainer.

Color intensifies in no time, but as both the joyous brightness of Dutch Interior and the acid pink and yellow of The Hunter. It intensifies again after Birth of the World. An opera singer from 1934 appears to scream. Is the joy gone forever? Not when another round of simplification can enlarge the organic shapes into fingertips of black and red. He has set out his vocabulary, and he can recombine and revisit it at will.

To what ends? Art, for one, and a critique of painting has to mean frequent stepping back. He does so in sculpture as well, building on the Surrealism of Jan Arp abd Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Naturally Miró's wood reliefs will have curved outlines like his figures and a multitude of staples like his marks in charcoal and ink. Emotional ends for another, and the curators, Anne Umland with Laura Braverman, connect darker and harsher emotions to Fascism and exile. As early as 1930, organic shapes and staples are matters of life and death.

Theirs is the standard account, and it has a serious basis in Miró's art and pain. Wood relief becomes a wood frame for a rope bundle, as if to bind the painted figures beneath it. Head of a Man from 1937 has pointed teeth and a scream. The sheer number of germ-like marks that compose a self-portrait from that year gives me the creeps. An old shoe occupies a radioactive landscape and lacks a mate. The ladder in a painting from 1940 provides a tenuous means of escape.

Still, an escape it is, with the first and finest of his red and black. And Miró is still recombining and reassessing events, emotions, and motifs. The shoe's acrid colors look back to the show's very first painting, a portrait of his studio-mate from 1917. Then he had a Japanese print on the wall, in deference to the tastes of Vincent van Gogh, and now he has van Gogh's old shoe. Escape Ladder has a concatenation of everything in Miró, with the red and black forms on top of every so many calligraphic traces and gradations going back to Birth of the World. A similar combination produces the poetry of The Beautiful Bird Revealing the Unknown to a Pair of Lovers in 1941, and its lovers have a comic smile.

Still, an escape it is, with the first and finest of his red and black. And Miró is still recombining and reassessing events, emotions, and motifs. The shoe's acrid colors look back to the show's very first painting, a portrait of his studio-mate from 1917. Then he had a Japanese print on the wall, in deference to the tastes of Vincent van Gogh, and now he has van Gogh's old shoe. Escape Ladder has a concatenation of everything in Miró, with the red and black forms on top of every so many calligraphic traces and gradations going back to Birth of the World. A similar combination produces the poetry of The Beautiful Bird Revealing the Unknown to a Pair of Lovers in 1941, and its lovers have a comic smile.

MoMA has more signs of rebirth with just four loans from private collections. One riffs on his Cubist still life from the same year, 1921, but with three creatures on the dining table. As so often with Miró, it is hard to say which is dead or alive. A second rope box adds a glimpse of what the show has to leave out, his working in series. "Painting and Anti-Painting" and a show of the Dutch Interiors at the Met hammered that home. The artist had no better always to start again.

This is not a postcard

No one can return to Catalonia or Paris in 1928, when Modernism was still dreaming. Miró at thirty-five had just had his third show, celebrated by André Breton himself. Years before, Miró had helped make transformation of the real the norm, peopling Catalan landscapes with hairy geometries that might have crawled out from under a microscope. A series called Peintures-Poésies must have seemed a textbook illustration for Breton's Manifesto of Surrealism. The nightmare in Max Ernst or Yves Tanguy had become a celebration. A painting from 1925 even bears the words Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves, or "this is the color of my dreams."

Nor can one follow the Spaniard north for a museum vacation, an escape from the acclaim, and yet another self-imposed displacement. The Met sees him as motivated by fear of succumbing to his own success. Today's celebrity artists might learn something. When this artist swore to "assassinate painting," he had to begin with a respect for the past. Where Dalí took Surrealism as a license to let his adult fantasies run free, Miró's fields of color never lose their grounding in the tradition of landscape painting and the actual landscape of his childhood. They really were the color of his dreams.

Museums then were quieter places, and Modernism had just restored Rembrandt and Jan Vermeer to the center of Dutch art. Miró, though, preferred something more boisterous, like Jan Steen or an obscure figure named Hendrick Sorgh. And he returned to his studio that summer with Dutch interiors very much in his mind. He stuck postcards to the wall as his models, and for all I know they are still on sale at the Rijksmuseum today. A small show, which originated there, brings together the postcards, the actual paintings by Steen and Sorgh, Miró's three Dutch Interiors and two related works, and a handful of paintings and drawings surrounding them. How much and how little he changed.

He combines a sense of child's play with something not at all suitable for children. And then he lingers over exposed butts or tortures spiders with the dedication of a nine-year-old boy. In Steen, children torture a cat by "teaching" it to dance, and a young woman implicitly flaunts her potential for pleasure by looking on. With Miró, one thing clearly has shrunk—the woman serenaded, now literally part of the furniture. Not that adult innuendo has gone out the window, like the tabletop with its own prominent rear end. It has just become the motor of painting as transformation.

He displays his sophistication in another way as well: his colors and transformations comment on his art. The lute player has morphed into an easel, with his head the hole and his hair the streaks of paint. Bare canvas saturated with color looks forward to Abstract Expressionism or even Minimalism. Surrealism here never becomes an excuse to discard Cubism. Rather, it is grounded in real memories and the materials of art.

With Ceci est le couleur de mes rêves, Miró builds on the Surrealist practice of automatic writing, which he had introduced into painting. He also builds on the self-conscious play on text, quotations, appropriation, and their contradictions in Picasso and Schwitters. Above the text, like a signature, sits a daub of blue paint, both a cloud as a metaphor for dreams and their literal color. At left floats another word, Photo, again in a fine hand. As Magritte might say, this is not a postcard.

"Joan Miró: Birth of the World" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through June 15, 2019, "Miró: The Dutch Interiors" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 17, 2011. A related review looks at his work from a single decade, starting in 1927.