Code Red

John Haberin New York City

Matisse: The Red Studio

Henri Matisse and his wife left Paris in 1909 for the same reason that many find it a challenge to remain in New York today. He had landlord problems.

Never mind, though, for they found a place to die for in Issy-Les-Moulineaux, on the outskirts of the city. He also found a studio to die for, nestled in the trees. He took it as his subject as well—more than once at that. The largest version, from 1911, hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, which recognized it from the moment it became available as among the most luxuriant and radical of his works. It was not, though, a quick sale. Now MoMA builds a show around The Red Studio, the studio itself, and the color red.

When Matisse paints his studio from his house two years later, he leaves it barely visible through the trees. He also allows the trees to grow out of sculptures on the window sill. This was a new start for him, but all his. He built the studio from scratch, but with its place in nature. Nature has its place, too, but within art. And that same dynamic offers insight into The Red Studio, the trouble it caused him, how it became a landmark, and how it came to be.

Un petit Luxembourg

The answers, as you might expect from a great painter, turn on everything he valued in life and in art. He could not leave Paris altogether behind, not when he and those sympathetic to him were creating modern art. Take it from Gertrude Stein, who should know. "The grounds were large and the garden was what Matisse between pride and chagrin called un petit Luxembourg," after the Luxembourg Gardens, between the Pantheon and Montparnasse. Henri Matisse must have walked there often from his previous studio near the Seine. Now he could have his own Paris, an ideal Paris in the suburbs, as a place to work and a work of art.

Listen to Stein again. "They were very comfortable and soon the enormous studio was filled with enormous statues and enormous pictures." An artist this ambitious could not settle for a decent workspace and storage racks. He needed his creations right before his eyes—to the point that they take over from the mundane realities of getting by and making art. When he painted an earlier attic studio, in 1903, it looks dark and cramped. Only a window at a peculiar distance holds out hope for the light and color he so loved, and now he could have it all.

If his new digs were not ideal enough, The Red Studio idealizes them that much more. A photo of the studio shows an easel, a well-stocked cabinet, a chair for his models, hardwood floors, and a broad patch of natural light. Not the painting. There it could pass for a fabulous living room, with paintings on the walls and more waiting to be hung. The cabinet could pass for an old-world masterpiece. A box of crayons, pastels, or colored pencils rests on a table in the foreground, as the sole sign of his craft and a way into his art.

Above all, there is color, as there had been in Fauvism from the start. This is, after all, a red studio. Matisse makes a point of it in writing to Sergei Shchukin, the textile dealer who commissioned the painting and invited the artist to Moscow to see how it would hang. He adopted Venetian red, Matisse explains, rather than the brighter red ocher that he had used before. He cites Stein, who called it the most lyrical of his paintings. He is pitching the work, of necessity, and Shchukin in the end turned it down. He drew back from a painting without figures, apart from the ones on the wall.

Shchukin may have balked (with the irony that textiles were once the Matisse family business, too), but the warm red changes everything. It covers every inch of the painting apart from his statues and pictures. The show exhibits The Red Studio amidst the work it depicts—six paintings, three sculptures, and one ceramic, with sketches toward a female nude that has not survived. They must have taken quite some detective work, and MoMA bills Ann Temkin and Dorthe Aagesen as merely the leaders of a larger curatorial team. A second room traces the history of the artist's studios and the painting's fate, but what does it say about his art? To answer, think red.

Color changes everything

History speaks of Pablo Picasso as line and Matisse as color. In practice, they influenced each other (the theme of "Matisse Picasso" in 2003), and Picasso would have seen The Joy of Life by his rival on his visits to Gertrude and Leo Stein. Still, color preoccupied Matisse every step of the way. It enters early work after Edouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard with their mottled light and sober colors. It motivated a movement, the Fauves (or the wild beasts)—and he broke with them only to paint his wife in 1905 with a green stripe descending from her forehead through her nose. You may know of The Joy of Life from the next year for its joyous colors.

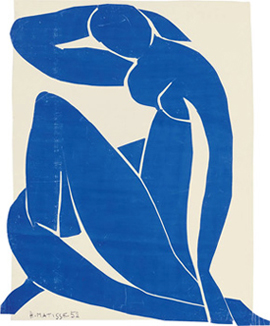

With The Red Studio, color changes things even more. An earlier painting has wood so rich that a table becomes good enough to touch or to eat, and he started the same way. But then he painted over the whole, with no break between walls and floor. The yellow outlines of furniture seem incised in red. It goes beyond the green and blue of Dance, from 1909, as the only hints of grass and sky. It looks ahead to the flatter colors of his late work in Nice, Matisse cutouts, like the blue nude here.

With The Red Studio, color changes things even more. An earlier painting has wood so rich that a table becomes good enough to touch or to eat, and he started the same way. But then he painted over the whole, with no break between walls and floor. The yellow outlines of furniture seem incised in red. It goes beyond the green and blue of Dance, from 1909, as the only hints of grass and sky. It looks ahead to the flatter colors of his late work in Nice, Matisse cutouts, like the blue nude here.

Critics attacked. The painting got only bad press at the 1913 Armory Show in New York. (At least it escaped the ridicule that descended on Marcel Duchamp and Nude Descending a Staircase, but then New York had a hard time with modern art.) It languished in (yes) the studio for fifteen years, until an upscale London club purchased it for the ballroom. The owner, David Tennant, felt betrayed when Matisse refused to buy it back. It fell into the hands of an English dealer who, eventually, put it up for sale.

By then, the story of modern art was coming together, and MoMA was eager to tell it, but were things that bad all along? Shchukin had asked for three paintings, and he did purchase one, a studio in pink. (He patronized Matisse yet again before losing everything to the Bolsheviks in 1918.) The Red Studio went on display anyway, in the second Post-Impressionist exhibition of 1912, curated by a pioneering arts writer, Roger Fry. Also an artist, Fry painted the Matisse room—but Matisse's influence was everywhere. He found another admirer in Albert C. Barnes and entered the collection of the Barnes Foundation in 1932.

It was never going to be easy, for all the pretense of luxury. Matisse planned the new studio in detail, but he relied on a maker of prefab housing for its execution. He had his avant-garde reputation, but shock at the avant-garde was real. And shocking it must have been to see what he called the "red panel." So what was it really about, the red or the studio? Look again at how color changes everything.

Unheard music

Shchukin had purchased a painting of a red room before—as one of three on the theme of harmony in the arts. Harmony in Red came first, followed by Music and a second version of Dance. And color gave Matisse access to harmony, all the more so when colors clash. They signal a break, from an everyday world untouched by art. The Red Studio depicts a place for art, but as a work of art in itself. It has left behind the painter and his models.

The equation of color and art began well before. Is the green on his wife's nose a natural highlight—or just, as the title has it, a Green Stripe? It transforms nature and art alike, even as it transforms her flesh tones, the black of her hair, and surrounding colors. And then there are the works seen within The Red Studio (two from Aagesen's National Gallery of Denmark), like a young sailor set against purple. Harmony seems out of the question, but only if one tries to detach harmony from sunlight or from art. Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter.

The rare object in The Red Studio that Matisse did not design, a wine glass, has its natural highlight, too, in white, but it is visible only against red. A curtain covers the single window, although an unseen fourth wall was mostly glass. The curtain modulates the light while isolating the studio from the vagaries of this world. It also places the painting in a long line of representations of the artist's studio—just as Joy of Life and Dance place him in a long line of pastoral landscapes, from Jean Antoine Watteau to the nineteenth-century picturesque. In depicting painted nudes in a painted studio, Matisse merges both genres. The work becomes a part of art history, but with a time and place in the present.

That time and place has room for you. You just have to be willing to enter art. The box of pastels is within reach, even as the red gives you nowhere to stand. Two stools have nowhere to stand either, although they function well enough as pedestals for sculpted nudes. A painting the following year, again in the studio, does have an easel, as support for nasturtiums, but are they, too, a work of art? The easel's back leg rests on the seeming ground of Dance.

Does color change everything but the works of art? Even those undergo changes. The scene recapitulates his career to date, but with updates for all that Matisse has learned. His Fauvist scene, a mill in Corsica, loses its dappled stone and broad sunlight in favor of two mere splotches of color. A third sculpture, hacked in wood, acquires a garland of flowers. Background clashes intensify, and the naked flesh in Le Luxe, its sole natural colors, become tinged with Venetian red.

Matisse may sound complacent or sexist, obsessed with nude women and cheap pleasures. Yet his women act very much on their own, in a world both present and apart. One of the three bathers in Le Luxe holds a beachball that I kept mistaking for a bouquet of flowers. Then, too, Matisse may be acknowledging his own weakness, by drowning his pleasure in red. He himself has nowhere to stand. The wonder is that he can still paint.

"Matisse: The Red Studio" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 10, 2022. Related reviews look at Matisse and Picasso, Matisse in retrospective, Matisse and textiles, and Matisse cutouts.