Poseur

John Haberin New York City

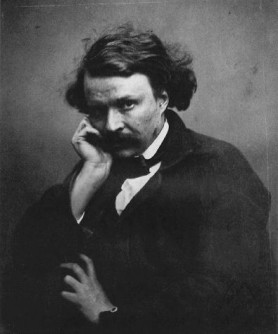

Nadar

In the 1870s, nearing the end of his career, Nadar photographed the Catacombs. The dark tunnels underneath Paris are packed with an eerie white lining of human bones. Then as now, it was a scene far harsher than even a photographer's artificial lights. In these images, however, the walls make at best an awkward impression, and the camera never lingers over the pale human remains. It stands apart, taking whatever angle and distance it needs to frame the cramped caverns.

Nadar's frankness foretells later documentary photography. Certainly it marks a break with the conventions of nineteenth-century studio work. He could easily be the dispassionate modernist facing his own aging—except for one thing. The Catacombs were just under construction. Paris was not uncovering its past but creating it.

In Nadar's wonderful retrospective, the Catacombs sit beside pictures of balloonists. They become an emblem with an obvious moral, death set against a daredevil future. The photographer's unpretentious eye reveals modern life as subterfuge—or theater. No one can avoid being excited. No one can help being bored and humbled by its changing roles. The artist above all must assume the role that art itself has shaped.

The casual observer obsessed with performance—the same sensibility governs the French photographer's well-known portraits. Sarah Bernhardt sits without a gesture. Only her arched pose establishes her famous presence. A black women, Maria, is allowed the dignity of simply asserting her bulk and her scowl. She is just one among many neglected servants of the burgeoning middle class.

Artists, writers, musicians, and actors formed Nadar's world, as they did for Julia Margaret Cameron in England or later Edward Steichen in his years at Condé Nast. I went to see what Doré and Ravel "really" looked like, and I reveled in an early shot of Baudelaire. The poet's head turns away toward shadow, as if seeking the night and solitude he so often celebrated. In a funny etching near the show's entrance, he and his peers snake in one long line around Nadar's sulking figure.

Taken together, these men and women survived by entertaining their public. They thrived, in turn, on confronting it. But if the artist equals alienated performer, what becomes of the artist's photographer?

Poseur. The French word has entered English, connotations intact. Posing means putting on airs, acting false to oneself. It is the plight of a woman every day before the mirror. Posing is also the job of portrait photography. In this dizzying hall of lenses and mirrors, Nadar's pretentious single name seems fitting, like that of artist as fashion designer or, for that matter, Knobkerry designs. And so does his innovative, unpretentious style.

Felix Tournichon, to give him his real name, first set up shop with his brother Adrien, who taught him to link scientific inquiry with theater. Adrien quickly documented the experiments of Dr. Duchenne, who sought exactly the physiognomy corresponding to each human emotion. A harsh grimace could even induce the right sensation.

These pictures blur the lines between spontaneous passion and pretence. No wonder Cindy Sherman admires them. They anticipate the increasingly high pitch of Sherman's funny, disturbing roles.

Soon, however, Felix took his own studio. Adrien insisted that his ideas had been stolen, but Nadar was surely in search of a theater without the grimaces. In his mature work, the artist can no longer pretend to scientific superiority over his subject. He has created the relationship to the sitter that still haunts modernist portraiture.

Fittingly, his greatest subject, collaborator, and alter ego was the most stoical of performers. Charles Debureau takes on the pantomime figure of Pierrot. He never exaggerates for the camera, and the camera in turn never presumes. The heavy shadows fully disappear, and the sitter smiles knowingly back at the viewer.

The Met itself presumes less intrusively than usual in the hanging and wall labels. In fact, it has the good judgment to make one print of Pierrot into the catalog cover. The white-faced figure, suddenly inseparable from Nadar or from the visitor, hopelessly points a camera right back.

The retrospective of Nadar ran in the late spring of 1995 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.