12.4.24 — A Dusty Square of Light

To wrap up from last time on late work by Robert Frank, he photographs his friends at ease together. Others turn their camera on him, like Joan Lyons and Danny Lyon.

His most obvious collaborations, though, were on films, starting in 1959 with Pull My Daisy He conceived it together with Alfred Leslie, with a script by Jack Kerouac, the author of On the Road. (Kerouac also supplies the voice-over narration.) It works through their shared ambivalence about their own creative past, with (as I put it in another past review), an undercurrent of humor and disturbance that art cannot resolve. It also moves between images of family life and the arts.

Some have found it formless, which misses its narrative, but also misses the point. It celebrates the lives of artists, including their spiritual life, but art that makes things up on the spot on the spot. And if it still seems formless, just wait till you see Frank’s other films. (MoMA gives them monitors rather than rooms to themselves.) Just wait, too, till you see the rest of his photography. He pops over to Coney Island for a shoot, but this will be one long roller-coaster of a ride.

His most persistent collaborator was his second wife, June Leaf, and their greatest collaboration their move from New York. They observe much the same scenes at Cape Breton, Frank in photography and Leaf on paper. She gives acrylic and ink the translucency of watercolor—to capture the light, but also to preserve in paint the spontaneity of drawing. She renders a hand, too, perhaps Frank’s own mark. They turn their thoughts most, though, to the space of a home. In years ahead, light can still penetrate, but little else.

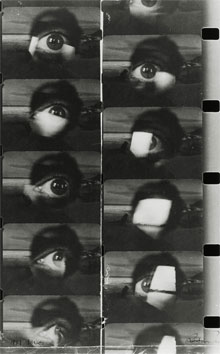

They differ in one thing: where Leaf’s scenes are otherwise empty, Frank is still asking his neighbors how they live. He seems happy to have discovered Mabou, a small town on the Cape where he can know pretty much everyone. They and their homes look ramshackle and improvised. One seems to be sinking halfway into the sea. A Mabou Winter is just a half-covered eye.

Walker Evans, long a friend and advisor, stops by to take a look around. For MoMA, it is just one more sign of collaboration. Even fans have mostly given up on Frank after The Americans, and the curators, Joshua Siegel and Lucy Gallon, hope to change that. Something, though, has changed for good. There is no getting around that images become closer and closer to throwaways, much like the “scrapbook.” Still, Frank knew the pain of throwing things away.

What remains is a portrait of loss. His two children died young, his daughter very young, and he himself retreats further and further within. He had always worked on the cheap, but now he trades his Leica for Polaroids—as he put it, “to strengthen the feeling.” Life Dances On . . ., the 1980 print that lends the show its title, seems more and more a bitter hope. Leaf’s absences of life become prophetic, and a typewriter rests untouched. An interior becomes bare walls and a dusty square of light.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.