3.5.25 — Live Evil

Ever wonder why pianos are black? Oh, sure, they come in white for the cheesiest of stars and Vegas acts, the kind that stop just short of dancing on the keyboard, but still with a touch of class. Julius Eastman was both cheesy and classy enough in his day to title a composition Evil Nigger, neither reigning in hell nor serving in heaven. He was, though, a serious avant-garde musician, and don’t you forget it.

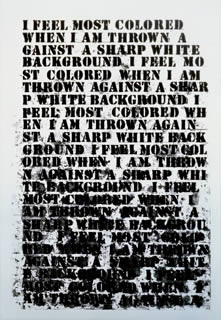

Glenn Ligon, for one, remembers, and he builds an exhibition around that composition along with baby grand pianos and his own celebrated paintings, as the very image of blackness. If piano keys are mostly white, you will understand, at David Zwirner/52 Walker through March 22.

Glenn Ligon, for one, remembers, and he builds an exhibition around that composition along with baby grand pianos and his own celebrated paintings, as the very image of blackness. If piano keys are mostly white, you will understand, at David Zwirner/52 Walker through March 22.

If you cannot decipher that image or pierce the silence, fine. These artists dare you to listen up. Both, too, know their way around jazz, where Miles Davis had his Live Evil. Ligon places a neon sculpture at the very center of the installation, with the opening syllable of Toni Morrison’s Jazz repeated and scrambled. Sth already sounds like a whisper akin to silence. But then his art often bears the marks of its own defacement or, deconstruction might add, erasure. The French for “under erasure” in Jacques Derrida is in fact sous rature, or scratched out.

Eastman’s composition sounds jazzy enough, too, when you can hear it. Just past the sculpture stand four pianos, with no performer in sight. Three, though, are Yamaha player pianos that kick in once a hour. It is worth the wait. Can music be at once lilting and brooding? His layered riffs on a single note sure is, and maybe a black artist has to be. As for the fourth piano, it is an antique for that touch of class.

The show also includes a print based a later composition, Thruway—where, you might say, the traffic barrels on through. Eastman’s rhythms guide a second neon as well, a wall sculpture, with the word speak blinking on and off in response. It appears a good dozen times within an oval, on top of the blinking, for repetition twice over. Ligon, now in his sixties, is a natural collaborator, who takes pride in his blackness but betrays uncertainty with each and every word. Ligon’s Whitney retrospective in 2011 seemed to grow out of a single text painting, Today I Am a Man. Rather than start over, allow me to refer you to my longer review then.

He was deceiving himself and no one. As an adult he was always a man, and white America could always deny it. He, in turn, could measure out the toll with repetition and erasure. A large text painting is pretty much illegible, and a still larger one approaches monochrome black. It effaces itself with coal dust, just as coal effaced working-class lives. The word America appears in large type upside-down, backward, and burnt.

Eastman, who died in 1990 at age fifty, gets a full wall for sketches and prints hung high and low. His words, too, could be confessional or a lie. If you cannot read them at that height and cannot make sense of what you can read, it happens. The score to Evil Nigger hangs by the front desk. It could serve as a score should, to lean on, or as just a teaser for his larger career as composer, pianist, vocalist, and conductor. Sth could also be the sound of words caught in his throat.

The gallery has featured blackness before in shows of Bob Thompson, Arthur Jafa, and Tiona Nekkia McClodden. Her title, “MASK / CONCEAL / CARRY,” could speak for them all. The space risks becoming making a ghetto for so prominent a Chelsea dealer, but I am not complaining. This is still Tribeca, and Ligon is exploring the limits of community and confrontation. He is also finding himself newly at home in collaboration. This is not one but two evil niggers.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.