12.3.24 — Restless Americans

To pick up from last time on late work by Robert Frank, that photograph of, just maybe, collaborators, should tell you something. They have been hanging out a long time now, and no one would dream of telling them how to pose.

Still, one appears behind the rest, on-screen or in a print, eager to join them but not altogether there. A couple hugs, but Frank stands apart at far right. He looks older as well, just short of sixty, with white hair and a scraggly beard. Hand-lettered labels below each person make them look like perps in police custody.

Still, one appears behind the rest, on-screen or in a print, eager to join them but not altogether there. A couple hugs, but Frank stands apart at far right. He looks older as well, just short of sixty, with white hair and a scraggly beard. Hand-lettered labels below each person make them look like perps in police custody.

Frank was always restless. He had to hit the road for The Americans, and it testifies to a restless America. I caught up with him at the Met in 2010—and do check out my review then, which I would not dream of repeating. The series makes the perfect contrast to “America by Car” by Lee Friedlander, for no one had his feet on the ground as much as Frank. He stuck to the people he met and the symbols they embrace, in unsettled compositions. He was not going to wait around for photography’s “decisive moment.”

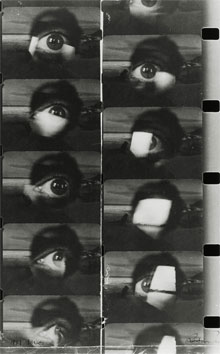

The book itself remained unsettled until practically the day of publication (in 1957 in Paris). Frank kept returning to his contact prints, circling and changing his choices. MoMA has it right when it includes contact prints among other discoveries, and it salvages film that he never released, too, as “scrapbook footage” in the basement theater. It boasts of its truth to Frank’s intentions by showing them in their entirety, but that has it wrong. He made his selections. He just kept changing his mind.

Born in 1924, he left Switzerland as a restless young man, and he could not sit still on his return to New York after The Americans. Sure, he could find a seat on the bus, but only to cross the city much as he had crossed the country—and to observe what he could from a window. From the Bus opens the show at MoMA, and it can be hard to know who on the street has made a decisive, theatrical turn and who has momentarily lost his way. Frank heads downtown soon after to what he could call home, east of the Village. He casts himself in a postwar scene that is giving America its integrity and its life. He still takes on commercial work, and MoMA includes a page from Mademoiselle, but with the freedom to say no.

He photographs artists, an incredibly young James Baldwin, and Allen Ginsberg, all of them friends. He could see Willem de Kooning at work from out his window, but he would rather photograph him up close. He spends an extended period with the Rolling Stones for what became his best-known group portrait. Naturally it is the period of Exile on Main Street. Still, he shies away from telling a story about psychology, creativity, and exile. He shoots painters without a brush in hand, Baldwin and Ginsberg without a typewriter.

Nor is he making a political statement. He has room even for a conservative icon, William F. Buckley. He must have known his own conflicting feelings about America. He had to keep moving, but he distrusted his adopted country’s restless spirit. To him it was the spirit of capitalism. It was time he refused to play the lone genius—a time for collaboration, and I continue next time with exactly that.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.