Is Modernism Marching Anymore?

John Haberin New York City

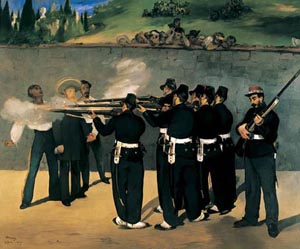

Edouard Manet: The Execution of Maximilian

Ambroise Vollard and Americans in Paris

A Third World nation threatens the economy of a great power, which responds by invading in the name of spreading democracy. The new leaders, reliant on a former regime for military advisors, truly believe that the people will greet them as liberators. Instead, the insurgency grows stronger, the invading troops must withdraw, and the country descends into violence. Artists do their best to stay objective, but their finest responses meet with censorship.

Angry yet? Edouard Manet would surely hope so, for the invaders then came from France. They also met with a revolution—and not solely in Mexico, where the French hoped to manage an empire. Manet's paintings of The Execution of Maximilian, part of a display at the Museum of Modern Art, continue the uprising that began with the Salon des Réfusés in 1863. It led to the dominance of the avant-garde in modern art histories.

By lucky coincidence, another small show tackles another illuminating episode in that history, as art approached a new century. The Met focuses on Ambroise Vollard, a dealer who promoted such lights as Cézanne and Picasso. Portraits of Vollard by them both could stand for the changes they brought. They change the way an artist constructs a painting—and in how a face reveals itself to the viewer.

And what of all the years between Edouard Manet and Vollard, when one should expect a great march from Impressionism to Modernism, not to mention their spread to America? The Met has an answer to that one, too, with an exhibition of "Americans in Paris."

A shot heard round the world

On June 19, 1867, Mexico overthrew its puppet government and killed the emperor, the former Archduke Maximilian of Austria. When the news hit Paris, Edouard Manet responded as never again in his career. He painted three versions, all on the scale of history painting, plus a lithograph. Given the scandal for the French monarchy, not to mention Manet's notoriety, he never saw them displayed, although the third traveled to Boston in 1869. The second ended up dismembered and partly lost, like his bullfight scene of 1864. Now the Museum of Modern Art gathers up the pieces from them all, along with an oil sketch and plenty of documentary evidence.

When the Frick Collection in 1999 exhibited Edouard Manet with Dead Toreador and other fragments from Incident at a Bullfight, it could have called the show "Manet and His Critics." One could call this one "Manet the Critic." It imagines him poring over the news, perhaps even some of the photographs and artist renditions here, as he makes sense of and in turn shapes the story. As usual, when facing the gritty realities of the present, Manet turns respectfully to art of the past. Like Pablo Picasso after many years with Guernica and Picasso in black and white, he leapt at the chance to take on Francisco de Goya and his Third of May, which Manet had seen in 1865. As usual, too, when Manet plays the old master, he begs for confrontation in the present.

In the incomplete first version, the executioners come dressed as ragtag guerrillas, and the victims all but disappear in gunfire. It shows one of Manet's fascinations, the illusion of immediacy, like the smoke from his previous stab at current events—a sea battle in America's Civil War. In the second version, he adds insult to injury, by giving the firing squad French army uniforms. He also supplies them with delicious blues, echoed in a new landscape behind. The last version borrows again from both Goya's darkness Manet's bullfight, with one's eye facing not just death but a frighteningly blank wall. It also has some of his crispest shadows and most startling contrasts of black and white.

Manet had every reason to despair. He had seen the monarchy overthrow the French republic in 1848, brutally suppressing a Paris uprising. He could almost be foretelling the violent end of the Paris Commune in 1871. Yet, like Goya in 1808, he does not express only republican outrage. His bleak picture extends to the Mexican rebels and even the onlookers. They lean over the wall in that final version like the gleeful crowd at a sports event.

One feels the brutality in the soldier's massed backs. One feels it in the horizontal line of rifles—and their preternatural closeness to their targets. Here the executioner's face is always well hidden, while death is literally before one's eyes. Photographs show the wall where any sensible firing squad would place it, behind the victims, to guard others from stray bullets. Manet has leaned not only on the facts, on Goya, and on man's proverbial inhumanity to man. More than the Spaniard, he seeks the banality of that moment between life and death.

The Modern has a point in showing these paintings with his implacably dead Toreador and his spookily alive Dead Christ Supported by Angels. Here however, more frightening than even death, one confronts indifference. A soldier in the foreground, face forward, reloads his rifle without the least acknowledgment of the events behind him or a viewer in front. Maybe Manet knew that the actual firing squad cheerfully posed for a group portrait.

Sitting in for Modernism

Ambroise Vollard had every right to grow tense. He had posed for the equivalent of two work weeks, not an easy investment of a dealer's time in 1899, when the avant-garde meant something: for artists at least, it could well mean poverty. In all this time, for days lasting into evening, Paul Cézanne commanded him to sit absolutely still, like Cézanne's Card Players or Madame Cézanne, and the artist never did declare the portrait done. He merely abandoned it, Vollard, and modern art to their fate. In the painting, however, one could easily overlook the tense, restless surface, for everything seems to point inward. A human life comes so close to a still life that one can understand the influence in reproduction on Giorgio Morandi.

These days one takes a seated portrait for granted. Photographers will do anything to give a subject dignity and to put a subject at ease. Once, however, those with sufficient wealth stood for their life-size portraits, and a still longer tradition demanded the clarity and reserve of head and shoulders alone. As art took on the middle class, women sometimes sat knitting or at the virginals, or businessmen sat to work at their accounts. In a seated, frontal portrait, however, as from Raphael or Diego Velåzquez, a chair meant a throne, with a pope's hands gripping each of its arms as a sign of command. Rembrandt's late seated self-portrait plays on that convention, but it takes the birth of Modernism to bring inner visions fully to the surface.

Vollard, his lips pursed and his eyes almost lost in shadow, bows his head and crosses his legs. The hand close to his chest clenches a book or perhaps his papers, and the other lies buried between his knees. The only other object in the room, a trapezoid near his head, might stand for a second book, its covers shut tight. The mysterious ovals seen through the window again redirect one within. They could pass for the back of Vollard's head in a mirror, although to modern eyes they look like nothing so much as the abstract Elegy to the Spanish Republic by Robert Motherwell. Even the choice of attire—a heavy coat and bow tie—speaks of repeated folding upon itself.

Vollard, his lips pursed and his eyes almost lost in shadow, bows his head and crosses his legs. The hand close to his chest clenches a book or perhaps his papers, and the other lies buried between his knees. The only other object in the room, a trapezoid near his head, might stand for a second book, its covers shut tight. The mysterious ovals seen through the window again redirect one within. They could pass for the back of Vollard's head in a mirror, although to modern eyes they look like nothing so much as the abstract Elegy to the Spanish Republic by Robert Motherwell. Even the choice of attire—a heavy coat and bow tie—speaks of repeated folding upon itself.

It may take a few moments to notice the patches of bright color everywhere. One can miss them entirely in reproduction, but in person they keep vision from ever sitting still. Despite the fall of natural light from behind, Vollard's knuckles have the strongest highlights—as much an expression of physical and mental tension as of the presumed light source to his right. Other bright areas add to the volume and concentration of his high forehead. They give the painting an unstable center, too, in the near vertical of his shirt front. Paul Cézanne declared that part of the painting a success.

Eleven years later, Pablo Picasso, too, painted Vollard as a study in restless intellectual inquiry, as also in a Picasso drawing. He surely had in mind an emblem of his own painting as well. Vollard's eyes narrow even further into slits, the bright shirt front fans outward, and that forehead seems in the process of exploding. At the height of Analytic Cubism, for once Picasso suppresses text, puns on the texture of materials, or hints of anything else in the room—almost to the point of inventing abstraction. This person and this art demand respect. I see little reason why not, too. Back then, a young dealer made a career by investing in art in cash, up front, including a slew of paintings by Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh that pretty much defined the avant-garde in the 1890s—and if Vollard turned handsome profits, so be it.

The Met tracks Vollard's patronage, including a beautiful display of the Paul Gauguin mural from Boston, some early Henri Matisse and late Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and any number of other lazy crowd pleasers. Portraits of the dealer occupy a room near the end, along with artist books that he commissioned. They bring his stable of artists together with Classical and cutting-edge literature. One could call the room a tribute to his erudition, his dedication to modernity, and his care for his artists. In the same room as Cézanne and Picasso, however, other portraits portray him as a balding, slightly dumpy, occasionally cheerful bourgeois. Well, some artists just see more than others, but the contrast allows a moment of reflection on the role of the art dealer as patron and entrepreneur, and it makes a nice jumping-off point for an otherwise safe show.

Not s'wonderful

What happened in Paris to shape modern art in those decades between Mexico's revolution and Picasso's? Visitors to "Americans in Paris" may think that they have seen it all. Surely those Childe Hassam flags or Augustus Saint-Gaudens figurines come from Philly, Boston, or, most often, the Met itself. Surely John Singer Sargent with Madame X or James McNeil Whistler's Woman in White dutifully appears whenever an arbitrary theme, like Manet and Spanish art, promises a blockbuster. Surely Claude Monet must have painted that poppy field before an American dutifully followed his model. And indeed he did, and indeed they have.

Americans like Gertrude Stein came to Paris before Gene Kelly, and the Met knows they still cannot get enough of it. A room of portraits suggests why. Those dashing figures include both high society and self-portraits, and one can hardly tell them apart. The subjects offer a balance of daring and comfort, not unlike the art—or, for that matter, like art now. At their best, like art now, too, every so often they can still stop me in my tracks. One can see why curators are eager to expand the Met's nineteenth-century wing.

William Merritt Chase's Dora Wheeler still has her improbably acid blue dress against a gold backdrop, on a narrow stage with no defined edges. Mary Cassatt's little girl still sprawls unsteadily on the furniture and shows her panties. On the other hand, for every Cassatt gaze observing everything but the viewer, more than a few here beg all too obviously for attention. For every artist soaking up Impressionism, like Dennis Miller Bunker's cottage drowning in sunlight, plenty went to study with the leading academic painters. For every composition as dark and slippery as Sargent's Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, any number revert to old-fashioned studio props and studio light.

Obviously the artists here had mixed motives, like Lyonel Feininger duking it out in Germany. They do not amount to a history of American Impressionism—which, after all, might have to unfold largely in America. They need not have painted French scenes, like Maurice Prendergast with his view of Central Park or Thomas Eakins in the New Jersey fields. They may not even have studied in Paris, like Winslow Homer, who merely wished to compete with Europe on his own terms. One has to ask whether the show began with a theme or merely the chance to cash in on the public's favorite half century. Perhaps one should treat the show's very tameness as a theme.

Some of this is fun to see, but I had much more fun asking why it seems so tame. Does it confirm the postmodern critique of the avant-garde as art for the new leisure class? Does it show, by contrast to these latecomers, Impressionism's revolutionary spirit? Does it mean only that a suitably unfocused selection can prove anything? Probably a little of all three, but I think the curators have a goal beyond pandering. They seek a revisionist account of the time, one that includes both Europe and America because it also includes what history normally leaves out.

Sometimes, as Ellen Day Hale or Henry Tanner, a black artist who drew on Eakins, diversity raises issues of gender and race, although not necessarily convincing me about the artists. Mostly, however, it offers what I might call the conservative version of Postmodernism: it wants to question the radical nature of modernity and the division between high art and low. It continues what the Met's nineteenth-century wing already announces, with its main corridor devoted to academic art and kitsch. Robert Rosenblum's exhibition of art from the year 1900 did the same thing, as if the sum of every work currently in Chelsea added up to art's past, present, and future. But can chronology alone substitute for history?

Manet's "Execution of Maximilian" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 27, 2007, "From Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 7, and "Americans in Paris" at the Met through January 28. Related reviews look at Cézanne's portraits, Cézanne landscapes, Cézanne's card players, and Cézanne drawing.