Modernism and Urban Decay

John Haberin New York City

Andrew Moore, Charles Sheeler, and Detroit

Why Art History Matters to Criticism

In 1927, Charles Sheeler spent six weeks in Detroit, at the invitation of the Ford Motor Company. He left enraptured by a twentieth-century "substitute for religious experience"—much as Charles Demuth that same year named a painting of a grain elevator My Egypt. Still, once he had known the substitute, there was no looking back.

Decades later, Andrew Moore is always looking back, but god has long since departed, along with more than half the population of Detroit. His photographs divide neatly between "then" and "now." Then, in 1950, Detroit was a center of industry, with Alfred Khan's reinforced concrete factories and a gateway to the city by the same architects as Grand Central Station. Now a third of its area stands empty. Massive rings that once rolled steel lie abandoned in the foreground. Shadows give way to red-stained walls and then a crystalline brightness, broken by two electric lamps still burning.

So at any rate says "Detroit Disassembled" at the Queens Museum, where wall labels focus not on photography, but on the then and now of history. In reality, Moore describes a more continual process of accretion and decay, like floors shaped ambiguously by peeling and accretion. The process unfolds slowly, and so do his photos. He captures a city at its worst, but where many a disaster scene has clear heroes and villains, his has a more subtle turmoil. Is Moore or, more recently, Frank Schwere or Marsha Pels merely milking decay, or can layers of history still matter to contemporary criticism? The questions will illuminate not just their visions, but also why I write.

Detroit dissembled

Then in his forties, Charles Sheeler had exhibited with Alfred Stieglitz and Edith Halpert. In collaboration with Paul Strand, he had filmed the mad perfection of Lower Manhattan. Ford modernized him nonetheless. When he returned to the Rouge River plant in painting, in 1932, he depicted a pristine façade. Even clouds approach geometric perfection. Is Modernism's success or the sad state of American manufacturing today a picture of stasis—or an unfolding, layer by layer in space, in texture, and in time?

Andrew Moore goes deep inside, where perspective accentuates a hall's grandeur but threatens to crush the viewer beneath its skylight. In Cass Technical High School, someone seems to have pillaged the chemistry lab while piling it high. His unfolding includes sudden shifts in scale, like the arch of Michigan Central Station that, on a second look, dwarfs a tall door. Another photo of the school could almost add more shelves and open drawers, but the grid amounts to classroom windows. Above all, however, the unfolding is in time, and the process is never clearly natural or artificial—just as abandonment implies both human action and entropy. In fact, entropy drives the chemical thermodynamics responsible for humanity.

People never appear, although they do in photographs not on display, but their traces are everywhere. Just try to pin them down. An interior contains peeling paint and chandeliers, themselves decaying, while a house is swept up in sunlight, mist, an alarm box, and empty streets. Bright green moss carpets Ford's former headquarters like Astroturf. Plastic sheets descend from a high window as if sunlight itself took a fall, and a fire left by the homeless burns below. Tires litter a collapsed roof as if dropped from still higher above.

The moralizing of ruins dates back before the founding of Detroit, the Detroit Museum of Arts, or Detroit art, and Piranesi made it his specialty in the mid-1700s. Yet his Rome was an intricate fantasy—and for him the very center of civilization. Moore, a New Yorker, seeks out evidence of decay wherever he can find it. Previous series have taken him to Cuba and Russia, with more static and less interesting results. He belongs to the fashion for disaster, like Deborah Brown and Eva Struble painting in Brooklyn, abetted by the strange mix of 9/11 and gentrification, or Jill Freedman some thirty years ago in midtown south. They take great care all the same.

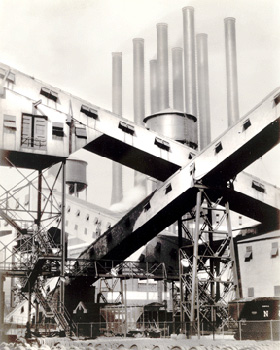

Ford may seem an unlikely ally for modern art. Then again, his aim of design affordable to the masses has its parallels in the Bauhaus. With Precisionism, America was just beginning to claim Cubism and Modernism as its own. One can feel the experience in Sheeler's photograph of conveyers—their windowed beams rising and descending below dark, silvery smokestacks. Moore's photographs, in contrast, come as elegies to Modernism as well as to Detroit, from Beaux-Arts towers to a video-conference room still waiting for the next call. At that high school, the numbers of a "national time clock" have crept down, like the melted watch by Salvador Dalí.

Much large-format photography today depends on artifice, like the model towns of James Casebere or the staged suburbia of Gregory Crewdson. Moore simply documents what he finds in 2008 and 2009, give or take the simply. I almost misread the show's title as "Detroit Dissembled." Still, there is much to be said for dissembling, dissemblance, and disassembly. Detroit may or may not recover along with its auto industry. But to adapt a friend of Demuth's, William Carlos Williams, so much depends on a white wheelbarrow littered with plaster and dust.

Some things never change

Before I continue a tale of two cities, a striking early postscript. After finding the review online, Moore was kind enough to send me two images. They show a more striking connection across time than I ever dreamed.

This is Building J9, from Moore himself:

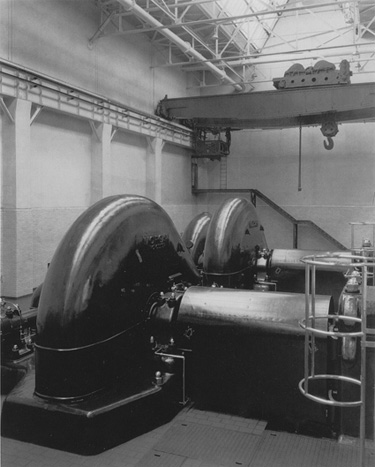

And this is Sheeler's Ford Plant, River Rouge, Bar and Billet Mill Motor Room:

Sometimes it is worth knowing a little history after all.

But were you shocked (shocked) to learn that Andrew Moore and Charles Sheeler had visited much the same Detroit? Imagine my coming just days later upon two more shared visions. They return to those factory interiors, but not for history lessons. Rather, they feel the consequences of abandonment and decay in their guts—one through a greater documentary realism, the other through imagined visions in three dimensions. Naturally they end up adding meta-layers of time and artifice to Moore's photographic elegy. No wonder Frank Schwere calls his photos simply "Detroit," while Marsha Pels calls her assemblage "Detroit Redux."

Schwere's prints lack Moore's scale, but they insist even more on the symmetry and grandeur of church-like façades and empty interiors. At the same time, they include a mark of angry humanity that Moore largely omits, graffiti. And I mean words like Vomit, not street art. Pels dominates the room, with two winged dogs glowing in translucent white as they pull not a sled but a damaged engine. They also pull it in different directions, as it chains them down. Over by a wall, gilded toy cars lie discarded in a pile of bones.

Work like this falls somewhere between Surrealism and camp, and your mileage may vary on just where. Schwere, in turn, made me appreciate that much more Moore's sense of detail, texture, and time. Paradoxically, by sticking to real materials and present-day realities, the artists may even fall prey more easily to "disaster chic," like the post-industrial picturesque of Leonardo Silaghi. Still, they remember the artlessness of suffering in the present, almost as surely as Richard Misrach. Pels also takes two bird cages, one with a slipper on a plush cushion, like a caged fairy tale. The other lays to rest a small piece of oxidized Detroit.

Awakening the dead

When you started reading, were you wondering how a painter as long ago as 1927 could have predicted the decline of the automobile industry or pressure on the Detroit Institute of Arts today? (And, if so, why he was too stupid to sell short and cash in?) Were you wondering why I was reviewing some dead artist or other at all, with so many fall openings? For that matter, if all these artists could go to Detroit just to look at abandoned factories, when will Henry Ford give me a free trip to the Detroit Institute of Arts? (I mean, they have this amazing Petrus Christus.) And how much worse could it be than Queens?

Okay, maybe not the last objection, but I did run into more trouble than I expected, and I want to tell you about it. It says something not just about why I write, but also about why, for better or worse, editors publish. I return to the topic from time to time, along with a critic's responsibility, online criticism, and why art takes words and not just looking. Excuse, then, another look back. The effort to weave between art history and contemporary art may sound no more daring than, well, appropriation. However, I have found a heady resistance to it, and I think that says something important about the desire for the new and about reader expectations today.

I owe the urge to see Andrew Moore at the Queens Museum to Mike Rubin in The New York Times, as well as to a lovely summer weekend. (Much of the crowded subway was headed to the U.S. Open.) The Sunday arts section can be uncritical, and I half shied away from Moore's grandiose prints and fixation with decay. Disaster chic, anyone? But I found myself lingering over disaster, and the Rouge River Plant instantly rang a bell. I recognized the name from a favorite painting in the Whitney, by Charles Sheeler, one that the museum has since displayed not as Cubism or Precisionism but as American Surrealism.

And could Ford really have sponsored Charles Sheeler's, er, plant costs in the first place? As I read more, to prepare for writing, it seemed almost too good to be true. The avant-garde truly was on the track of modernity and progress, and a comparison with the present offered a parable of Modernism and industry. I had my hook, words came, and the imprimatur of The Times surely made Moore a marketable subject, so off the draft went to a magazine that had run reviews of mine in the past. But no, I heard: we do not run reviews of dead artists.

Obviously Moore is very much alive (and so, for now, is Ford as a company), but I learned again an old lesson. People do not often read past a first sentence, and they are bored silly by history, theory, or context. I learned it again two months later, when I tried to evoke another artist's magic by describing a first encounter with his installation in real time, in all its surprises. What, I heard back, is this? Here the editor was, no doubt, standing in for her readers. Just give us the facts, up front—and what to do with our weekend.

Global markets, gentrification, and a growing outreach to the rest of us go together. They mean more galleries, more art fairs, more international collectors and art advisors, more attention to street art, more open studios, more MFA grads, a wider public for openings, and a serious questioning within art of the division between "high" and "low." They also mean daily journalism that, for maybe the first time, takes art seriously, with writers as thoughtful as Roberta Smith and enthusiastic as Jerry Saltz. Yet they also mean shallower arts magazines, with shorter articles, more puff pieces, a fixation on the latest thing, and fewer critics who will shape how others think about art and culture. I still think that criticism can do better—and that you can get to the end of a review intrigued, excited, and still not sure how much I even like the artist. I may be wrong, but that is why I still depend on the Web and why this site reads so little like a blog.

"Andrew Moore: Detroit Disassembled" ran at the Queens Museum of Art through January 15, 2012, Frank Schwere and Marsha Pels at Schroeder Romero & Shredder through February 11. Moore was kind enough shortly before the show closed to send me that pair of photographs from himself and Sheeler that, although he may or may not have planned the parallels, have a startling clarity all their own. He stuck to the fact-based universe of art, and both photographers deserve every credit and more. I should note that the Detroit Institute of Arts attributes a painting I mention to Jan van Eyck, and debate has raged for decades whether to attribute much or all of it to assistants including Petrus Christus, much like a "Virgin and Child" in the Frick. I guess I just have to see it to know for sure. A related review follows Andrew Moore to the Hudson River Valley.