A Very Public Collection

John Haberin New York City

The Detroit Institute of Arts: An Introduction

It was an expensive shopping trip, and I still left empty-handed. I have never been more grateful.

I had seen one paradox after another. I had seen historic landmarks and faceless glass towers, new communities and abandoned buildings. I had seen a city of highways and hopes, of busy restaurants and utterly deserted streets. I had seen a city staking its future on tourism, with maps everywhere downtown and a revived waterfront walk. I had seen, too, a city that had talked about throwing its single most important tourist attraction away. I had had my first glimpse of Detroit.

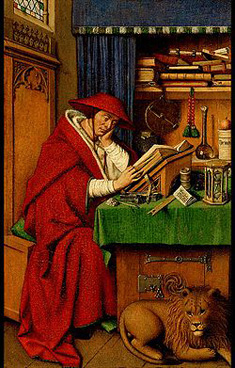

I had seen, too, the Detroit Institute of Arts, where thankfully nothing was for sale outside the bookstore and cafeteria. I was joking about shopping, but a city strapped for cash really had floated the idea of selling off its highlights or even the building. An auction house duly offered its appraisals. For now, private donations and a successful end to bankruptcy proceedings have saved the museum, with promises in place of a self-sustaining institution. I could not walk off with favorites like Bruegel's Wedding Dance or a Saint Jerome in His Study begun by Jan van Eyck, even if I could afford them (and an accompanying post contains additional images). But I knew that I had, at last, to see them.

The grand tour

I had been thinking about a visit ever since the city's finances made the headlines, and I have offered my own defense of preserving its museum. A summer group show, on the theme of Detroit's legacy for contemporary art, only added urgency. The Detroit Institute of Arts was one of the very few American museums that I had never seen and by far the largest. In person, too, I could hardly miss what might have been lost. Who would imagine a buyer for an institution spanning a city block—and a collection spanning centuries? And who would imagine a future for so many histories if the highlights alone vanished into private hands?

I am talking about a public collection and a public legacy, and the museum knows it. One can see that awareness everywhere inside. Like the freestanding plaque before a choice painting in many rooms, with commentary keyed to insets, wall labels are kid friendly and less into scoring curatorial points than at the Met. One can see it, too, in the unique attention to African American art. A big mosaic by Romare Bearden hangs outside the space for temporary exhibitions, Ed Clark shares a wall of postwar abstraction with Willem de Kooning, and a room in the American wing calls attention to black responses to Civil War art and the Hudson River School, including a local hero, Robert S. Duncanson. Four more dedicated rooms top off contemporary art with such artists as Al Loving, Benny Andrews, Howardena Pindell, Glenn Ligon (with an accompanying soundtrack by Billie Holiday), and Kehinde Wiley.

One can see the museum's public role, too, in its otherwise forgettable architecture—an accretion over the years of Beaux Arts, Renaissance, and modern. It opens onto more than one street, a puzzle that its layout never quite solves. It has courtyards as display or gathering points, for a fair degree of wasted space—if nothing like the hostility to art of all those humongous museum atriums elsewhere. It has an especially popular court for a 1932 vision of Detroit and its industry by Diego Rivera. As usual, the Mexican artist did not let such minor details as a commission stop him from an energetic tribute to labor or a less than flattering look at capitalists on and off the factory floor. His sweeping rhythms, fresco hues, and unsparing realism unite multiple scenes on multiple layers of facing walls.

The separate entrances trail off into dim rooms for Native American and non-Western cultures. If this shopping trip has a bargain basement, it is here. Still, the first floor announces right off that this is a major museum. Not just the Met has an Islamic wing, although this one has more ceramics than miniatures. The museum defers to its third floor not just decorative art but also Dutch masters and a so-so collection of France and England in the era of revolution. Maybe those rooms are too small for much else, but Detroit also gets to proclaim its inclusion of modern art on the second floor, right alongside Western painting.

That floor also has the museum's true welcome and one last reminder of a public purpose. Before one reaches distinct periods in European art, one can join a tour of Europe. Does that make you think of Americans in the age of Henry James and Edith Wharton? Here British and European artists visit Italy. Mostly that means Italy of the eighteenth century—the century of Caneletto, Piranese's dark architectural fantasies, and Tiepolo's Venice. By putting visitors in the place of artists encountering them, the wing frames the entire museum as about learning about art.

Michael Sweerts from the Netherlands pictures a young man eying plaster casts, as artist or collector. A self-portrait by Nicholaes Bercham, in all his Dutch calm, hangs next to a glowering Salvator Rosa. Thomas Gainsborough, Peter Paul Rubens, and Diego Velázquez all get lessons in portraiture. Not that they cease experimenting on their own. The lumpiest face is the Spaniard at his frankest and most informal. A prince on horseback echoes Rubens's lost portrait from 1628 that influenced Velázquez as well. Leonardo was there first in sculpture, his rearing horse defying gravity, but Rubens turns a warrior's madness into a ruler's stately procession.

Paired histories

Rubens is only the first in the museum's highlights, at his warmest even when putting on a public show. The looseness of that equestrian oil sketch signals a workshop production, but it also adds humanity. A Biblical scene shows Abigail bringing gifts to King David, to forestall his turning his lust for her into revenge on her husband. They lean toward one another as a meeting of peace and war, and peace wins out. Its side has, after all, the most muscular man bearing bread and an ass that looks smarter than the rest put together. They also leave one ready for a step past Italy—toward a museum tour of one's own.

Talk all you like of the virtues of "slow art." On first trip like this, you just learn to go faster, even as you remind yourself to keep stopping along the way. Maybe later you can revisit the collection in memory, and maybe memories come alive in pairs. The anxiety of Parmagianino at the new-born Jesus looks all the stranger and more familiar after Carlo Crivelli's heartfelt Lamentation half a century before. So does the eggshell bulk of a mother and child by Bronzino after the calm solidity of a Madonna and Child by Giovanni Bellini. See why I think of Mannerism as a Post-Renaissance?

Triptychs from those same years in northern Europe, by Joos van Cleve and Pieter Coecke van Aelst, make a donor's prayers the quiet foreground for not just the Bible, but the turmoil of a modern world behind. Coming to the Baroque, remember the Met's case for Artemisia Gentileschi and her savage assertion of a woman's dignity in light of her father, Orazio? One can see them on facing walls in Detroit. Approaching Modernism, self-portraits by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin look confident but down-to-earth. And then the strangeness in one of van Gogh's favorite subjects reappears in sunflowers by Emil Nolde. A portrait has Pablo Picasso on his way to Cubism, and then a nude has André Derain on his way from Cubism and toward a mix of classicism and sexuality.

Triptychs from those same years in northern Europe, by Joos van Cleve and Pieter Coecke van Aelst, make a donor's prayers the quiet foreground for not just the Bible, but the turmoil of a modern world behind. Coming to the Baroque, remember the Met's case for Artemisia Gentileschi and her savage assertion of a woman's dignity in light of her father, Orazio? One can see them on facing walls in Detroit. Approaching Modernism, self-portraits by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin look confident but down-to-earth. And then the strangeness in one of van Gogh's favorite subjects reappears in sunflowers by Emil Nolde. A portrait has Pablo Picasso on his way to Cubism, and then a nude has André Derain on his way from Cubism and toward a mix of classicism and sexuality.

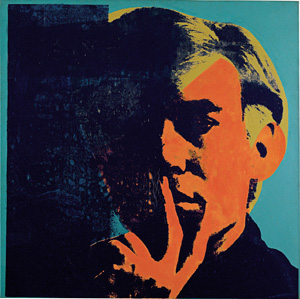

Reaching across time and rooms, one can create new art histories. One can compare the pillars of light in abstractions by Charles McGee, the African American artist, and Barnett Newman—or in stained glass by John La Farge. One can picture a canvas by Sam Gilliam as a tapestry, like the one in an austere but sun-drenched interior by Charles Sheeler. One can imagine an anonymous sixteenth-century jester alongside a stern Max Beckmann staring out from behind his easel. Or one can leave Andy Warhol beside himself, in a double Warhol self-portrait. Fra Angelico does quite well on his own as well, with separate frames for Mary and the angel of the Annunciation.

Jacob van Ruisdael alone offers two paths into history. Is his Jewish Cemetary, as the wall label suggests, a lesson in how everything must die? Even headstones must return to nature, worn by the rain and shattered by light. Then again, next to it Ruisdael offers a landscape of sudden descents, and yet a shepherd and his flock easily ford its shallow river. Clouds take on an almost human presence, and distant hills align as a path across the earth. Moralism got along fine with Dutch pride in an emerging nation, and what could be a more enduringly human landscape than a cemetary?

Would you rather live in memory with one artist at a time? If I had time for just four works, I might work back from Frederic Edwin Church. His Cotopaxi from 1862 has at least four centers of light—the erupting volcano in the Andes, the disk of the sun veiled by a curtain of dust and refracted light, the sunlight peaking out from the other side of the volcano from within a cloud, and the intense reflections off a lake, rocks, and a waterfall closing in on the picture plane. The American kept returning to the site in Ecuador, but never with the same puzzle of day and night. Is this the ultimate in realism, cutting-edge science, or myth? Church makes a point of them all.

A member of the wedding

From there, one can return to the very origins of the Baroque and art's discovery of interiority and self-reflection. Repentant Magdalene by Caravaggio has lost some of its surface, from 1598, but I will put my shopping money on its being his—nearing the end of his stay in the Cardinal del Monte's household in Rome. Mary at the center is still one step away from repentance. Yet she holds her flower close to her heart, and her sister seems so distraught as to be pleading with herself. Mary also draws most of the light, that natural or divine illumination reflected as a small pillar in a darkened mirror. To look into it is to look within.

For Pieter Bruegel around 1566, a painting was still very much a public occasion—not unlike a peasant wedding. Bruegel's Wedding Dance has a bird's-eye view that insists on its objectivity. Yet it is also a close view, one that engages the viewer with its empathy. Dancers look foolish, leering, overweight, and drunk. Even the most knowing is about to make his move. Yet they all come together in Bruegel's earthy colors and the dance.

If I were really shopping with several million in hand, I might stop there. Estimates assign much of the collection's worth to only a few paintings, this one topping the list. Personally, though, I prefer one last step back, to the early Northern Renaissance. Probably Jan van Eyck never finished his Saint Jerome, from around 1435. Could it have fallen to his most prominent pupil, Petrus Christus? Scholars argue over the chronology of work by the Jan van Eyck, but I still treasure this one for Petrus Christus.

van Eyck is present in the shadows deep within the saint's interior. His light reflects off an astrolabe, piercing a vial and an hourglass. His precision makes the tiny script on a letter legible to this day. His investing the visible with meaning is clear in them all. One can interpret the apple, a druggist's jar, and the chemicals in the vial as a narrative of fall and redemption—the same as in Jerome's Bible. As for the lion, you may recall that the saint made a friend for life by removing a thorn from its paw.

Did you notice that van Eyck's hand thus lies in objects, on shelves behind a drawn curtain? The perspective converges there as well. This artist cared more about art, light, and meaning than about his supposed subject, which he left to others. There I feel Petrus at work, in the broader brush of the saint's red cloak and the almost comically tame lion. Petrus trusted to the everyday, including Jerome's task of reading. The saint leaning on one arm, fingers caught up in the book, could be intent, thoughtful, or just plain bored.

Like Petrus, Detroit and its museum will have to hold up against serious competitors. The Detroit Institute of Arts has its gaps. Its best example of Impressionism is by an American, Childe Hassam. Still, it deserves a future—and one that preserves and builds on its past. It is a public collection, a public resource, and a public responsibility. Each and every citizen can be a member of the wedding.

I visited the Detroit Institute of Arts in late August 2014, and on November 8 a federal court approved the "grand bargain" that will save the collection and that allowed the city to exit bankruptcy proceedings December 10. The collection will pass from the hands of Detroit to a trust. A related review makes the ethical and financial case for preserving the collection. An accompanying post contains additional images.