Savages and Sophisticates

John Haberin New York City

Paul Gauguin: Prints

Woodcuts and the Modern Book

In all of Paul Gauguin's prints at the Museum of Modern Art, the artist appears just once. One might easily miss him, but there he is—his pencil mustache and face, still youthful well into his forties, on a busy sheet of what could be studies or fantasies. As always, most are of women, surrounding him like thought bubbles. When women sleep, Gauguin dreams.

He was not the only dreamer. Like Gauguin, other artists were turning to older means of printmaking. Did they "make it new"? With "Medium as Muse: Woodcuts and the Modern Book," the Morgan Library stands Ezra Pound's imperative on its head.

It shows artists turning the page back, in the face of threats to craft, to reading, and to humanism from photography and the pace of modern life. Drawing largely on its collection, it also traces the "woodcut revival" to nineteenth-century movements, starting with Romanticism. It argues for Modernism as born of something old, something borrowed, and in its melancholy imagery something blue. And yet it still delivers the shock of the new.

Print as experiment

Paul Gauguin sure did his share of dreaming. MoMA has some one hundred sixty works, including thirty paintings and sculptures, with ceramics and reliefs carved from tree branches and trunks. The rest, though, are works on paper, starting with his first suite of prints in 1889, the year he quit his job as a stockbroker at age forty-one, as the market crashed. Two years later, he was off on his first of two trips to Tahiti. The eleven prints in that first series range from café society seen as specters, to a Caribbean landscape of brooding trees, and to memories of Breton girls from his paintings. With the next series, his first woodcuts, he has found Noa Noa (or "fragrant scent") and lost himself in his dreams.

He also has more than his share of women. Not all are sleeping, and they are wrapped up in their own dreams, not reclining just for him. When they are standing, they have hard glances and arms by their side or overhead, elbows bent and firmly on their own. Many pay the viewer no attention whatsoever. Even Eve holding a leaf over her crotch betrays no shame, while the devil himself looks scared. Men appear far more rarely—and then most often as brutes or gods. Even when lovers embrace, they resemble in their pose a mother and child.

The women have, shall we say, an ambivalent relation to the male gaze. They are neither the compliant odalisques of art from J. A. D. Ingres or the Paris Salon, nor direct confrontations with tradition, from Edouard Manet's bar all the way to Cindy Sherman in the present. They are more self-possessed and less idealized than one may remember, but also at the very center what Gauguin called his "ultra-savages." One had better set aside more than a few expectations.

For one thing, one may expect the working out of ideas, in what look like rough sketches toward a painting. Yet these are prints, most of them after paintings and reversing the image, starting with those Breton girls in their triangular bonnets. Gauguin created that series at the urging of his dealer, the brother of Vincent van Gogh, and a later suite for sale by Ambroise Vollard. Often he takes a single figure from a painting. He likes to exploit the figure's isolation, in a deeper and darker space or, conversely, to approach abstraction. He may set aside his own myths or accentuate the dream.

For another thing, one may expect from prints a degree of finish rather than the dream. Instead, Gauguin is transforming images, with as many as nineteen variants on a single print. Even monotypes, made from oil or watercolor on glass, can serve for a second or third impression. In woodcuts, he keeps sanding the wood and incising again, often in thin parallels rather than blocky outlines, like points of light or a shower of rain. A figure may slip into darkness or toward a flame, and black may become white. A nude in fetal position may become an offering of bread on a plate.

The curator, Starr Figura, presents an experimenter, starting with those very first prints, which adapt lithography to zinc plates and take to yellow paper made for posters. They disrupt the very distinction between printing and drawing. When Gauguin dabs color on one sheet of paper, lays it on another, and then completes the "oil-transfer print" by incising the reverse with a pencil, who knows which to call it? When he lays one print over its reverse, is he having second thoughts or insisting on opposites? One way or other, he is questioning the purity of a medium, along with the purity of his subject. And that may unsettle one more expectation, about Gauguin's regard for the primitive.

Hybrid and purity

When someone turns to art full time at age forty-one, one can fairly expect him to come to it with strong opinions. And when he heads for the South Seas, first to Tahiti, already far from unspoiled, and then to a remote village on the Marquesas Islands, one can expect him to impose that attitude on others. So it is with Gauguin and his women. He wants to have found paradise, and he wants it to be filled with devils. He wants it to answer, as the title of his largest painting has it, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? And he wants to grow closer both to nature and to myth.

He brings more than his share of myths with him. He places Tahitian women in the garden of Eden and the Gospels, and he patterns them after the Parthenon frieze and a Buddhist temple. He invokes an entire pantheon of local deities, but then he also makes up one of his own—the goddess Oviri, or savage. He sounds like the European sophisticate in search of the noble savage, and he is. He sounds, too, like Joseph Campbell in the twentieth century, peddling mythic variations on the universal. Yet one can also see him as undermining the very possibility of a universal, for any one myth can become another.

He saw himself as a "savage," not a cultural imperialist, and he started a newspaper to satirize the colonial administration. Prints for French dealers make him a kind of reverse missionary, bringing native traditions to Europe. Yet he again looked two ways, just as with his media. He is the hybrid in search of purity, in series that can depict Delightful Land and Eternal Night. He found his ideal at last but quite possibly attempted suicide once he found it. And he treats women as both down to earth and in the shadow of the gods.

He saw himself as a "savage," not a cultural imperialist, and he started a newspaper to satirize the colonial administration. Prints for French dealers make him a kind of reverse missionary, bringing native traditions to Europe. Yet he again looked two ways, just as with his media. He is the hybrid in search of purity, in series that can depict Delightful Land and Eternal Night. He found his ideal at last but quite possibly attempted suicide once he found it. And he treats women as both down to earth and in the shadow of the gods.

An exhibition like this, with a popular artist and an unfamiliar artistic process, shoots for the blockbuster while pleading the excuse of scholarship. The Met did much the same with van Gogh drawings in 2005. Yet it works, by replacing the standard picture of the artist with the experimenter. With his sculpture in wood, he is imitating totems, but he is not above sticking in a profile or sticking out a pair of buttocks. With his smearing, wiping, and smearing again, he may bring out or hide the grain of the wood. And which version, he seems to ask, is more atmospheric or more real?

"Paul Gauguin: Metamorphoses" may help those, like me, who can never quite deal with Gauguin's primitivism, mysticism, and handling of women. It may work best of all by the chance to look again at more familiar art. Interesting as the prints are, the oil colors and larger compositions of his paintings look fresher by comparison. Light dapples deep blue water in The White Horse—which turns out to describe a gray-green horse drinking while red and purple horses slip behind a tangle of branches like the lead in stained glass. The only white belongs to a flower at their feet. Flaming shadows and mysterious concentric circles of color lend the calm seated figure in Girl with a Fan, from the year before his death in 1903, a sexuality out of Balthus.

The ambiguity of hybrid and purity extends to the paintings as well. With Two Tahitian Women, one woman faces front with an earthy humanity and a dark blue waist covering, arms crossing beneath her bare chest. The other leans toward her shoulder, in skin tones darkened by nature or shadow, in a pale blue robe. An ascending curve unites them against sunlight breaking through the leaves above. Is the weaker looking to the stronger for comfort, or is a single figure exhibiting her dark side, and which embodies Gauguin's dreams? Modernism's radical transformation of sexuality and representation is barely a decade away.

Musing on woodcuts

At the Morgan, one may as well enter the drama in the middle. Well, since this is a show dedicated to books, make that in medias res. Visitors who take the stairs from the old library, rather than the elevator from the seriously modern museum atrium, will find themselves around 1900. Many of the names will be familiar, and so will what woodcuts meant for their art. For Camille Pissarro, a firm but sinuous line brings the sensation of the outdoors. For his son Lucien and for Félix Vallotton in 1891, like for Naudline Pierre today, it approaches Symbolism and the art of Japan.

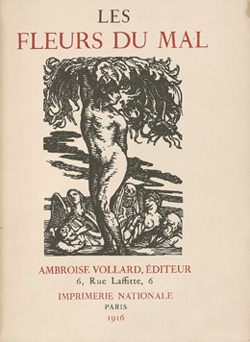

For Gauguin, harsh contrasts and dark glances fit with the rawness of the primitive. For Aristide Maillol in 1915, they lead to sculpture. For Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Max Ernst, they exemplify in turn German Expressionism and Surrealism. When MoMA picks up Gauguin's prints in depth, it finds a great deal more than blocky outlines and crude emotions. At the Morgan, one sees instead his influence on Emile Bernard, who in 1916 illustrated the very prophet of modern life, Charles Baudelaire. It was an edition edited by Vollard, the avant-garde dealer who sat for Pablo Picasso and Paul Cézanne.

The shock of the new continues well into the new century. Woodcuts helped Lynd Ward to capture the stifling rhythms of factories soon after the Depression. They allowed Penguin Illustrated Classics to democratize reading and Rockwell Kent to teach bookmaking to America. If the medium's bluntness makes you think of Claymation, Berthold Bartosch in 1932 turned it into film. Vallotton and others ditched the text entirely, for what Frans Masereel in 1920 called a Story Without Words. The show's very title echoes a formalist's wish for art as object and a medium as true to itself.

If threats to reading from new media sound all too familiar today, the Morgan ends with contemporary book design. It includes Barry Moser's Alice in Wonderland, the graphic novels of Art Spiegelman, and Gaylord Schanilec, who renders a midtown subway platform with photographic clarity. Then, too, Postmodernism has its own word for stealing an older art and turning it against itself, appropriation. Schanilec indeed calls his color woodcut New York Revisited. Craft and primitivism also parallel renewed interests not explored here, in design and folk art.

This art may be modern, but it is hardly another Futurism, with the cry to "demolish the . . . library." The Morgan has been reaching out to contemporary art lately, with Matthew Barney and photography, but its heart is still in the past. It may not survey the centuries of woodcuts beyond books, but it does have a display case "master class" introducing the techniques and an example from the Renaissance. More to the point, it focuses on a movement for which woodcuts are the past—and one worth recovering. The messy time line centers on the nineteenth-century Arts and Craft movement, with John Ruskin as its voice and William Morris as its leader. In the "ideal book," as Morris put it, image and text form a harmonious whole to convey beauty to the masses.

From there, it is one step forward to the pre-Raphaelite lushness of Edward Burne-Jones, for Morris and his Kelmscott Press, and to William Nicholson, who borrowed an older term for wood engraving in his alphabet book of 1897—in which X is for Xylographer. And then it is one step back to Thomas Berwick around 1800 and such visionary contemporaries in England as Edward Calvert and William Blake. No one could integrate text and image so well as the poet and artist of a fallen world. Ironically, Berwick's "white-line revolution" succeeded thanks to a technological advance, a harder wood that could stand up to steam-powered printing presses, while Blake executed his reliefs not in wood but in pewter. And while they sought the look of a woodcut, an older artist like Albrecht Dürer prided himself on bursting its limits. The medium is again the muse, and artists may still make it new.

The prints of Paul Gauguin ran at The Museum of Modern Art through June 8, 2014, "Medium as Muse: Woodcuts and the Modern Book" at The Morgan Library through May 11.