When Modern Meant Graphic

John Haberin New York City

German Expressionism: The Graphic Impulse

When the Museum of Modern Art calls its show of German Expressionism "The Graphic Impulse," it truly means graphic. Those barely twenty years span dance halls, dark streets, syphilitic prostitutes, labor unrest, and economic turmoil, broken only by a war of unprecedented brutality—all rendered as explicitly as humanly possible. It says something that the Expressionist movements first exhibited in an empty butcher's shop. If these artists could exaggerate sheer chaos, they would.

Of course, graphic here means first and foremost works on paper, supplemented by a few key paintings and almost all from the permanent collection. However, graphics inspire every form and medium. Posters as well as fine art converge on a single impulse—to protest against the present. Older graphic media, too, serve as models for an art distinctly of northern Europe. Lithographs imitate the spare, thick, angular lines of modern woodcuts, often in grainy prints to simulate fine rag paper. They envisage Modernism as an alternative premodern art history.

Otto Dix's immense War alone could stand for a graphic art of observation, experiment, and sheer revulsion. It appears in its entirety, not as a series or an artist's book, but as notes from the front, in graphic impulses flung everywhere up, down, and across a central wall. It is also surprisingly realistic—if skulls crawling with maggot-like humans or living skeletons can be real. The ghouls are merely men in gas masks. The scars on the battlefield appear left for good. The fatigue and tenderness of men carrying the wounded are real as well.

Metropolis

The show also presents an alternative history of Modernism and of the museum itself. Pointedly, it takes the galleries most often reserved for blockbusters, while Picasso's guitars must settle for downstairs, near rooms for prints and drawings. With very few loans indeed, from the Neue Galerie among others, it boasts that MoMA is not just about Paris. Even more than the previous exhibition in the same rooms, "On Line," it rewrites Alfred Barr's notorious genealogy of modern art. The roughly two-hundred and fifty German Expressionist drawings and other Expressionist works on paper seem largely indifferent to Cubism. Here space is compressed rather than fragmented and multiplied, while real bodies shatter.

The exhibition may rewrite other memories as well. Expressionism makes many people think of the horrors of World War I, runaway inflation under the Weimar Republic, and art suppressed by Hitler as "degenerate." The Guggenheim told a version of that story the summer before, when it introduced Neoclassicism through excerpts from Dix's War—as if the entirety of postwar art rebelled expressly against him. In reality, any proper textbook opens not long after 1905, with the founding in Dresden of Die Brücke by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rotluff. When Weimar in fact stabilized its currency in 1924, deflation wrought havoc with the market for prints like these, and the movements all but ended a few years later, with the Nazis barely on the horizon. The artists had pretty much burnt themselves out anyway.

Things get going with three independent groups, each given a room. Die Brücke promises literally a bridge to the future, but it is already burning its bridges. Kirchner paints a street populated by fashionably dressed people staring straight ahead like specters. The city presses in on their forced march and presses them forward, directly at the viewer. On paper, Heckel tries to recapture a past truer to Germany, in landscape, but that idyll, too, is shot through with corruption. Female nudes lie as inert and exposed as corpses, perhaps especially while exposing not their pastoral innocence but their crotch, in a style that still inspires Jan Müller and Helen Verhoeven.

The second scene introduces the Blue Rider, led by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, here too with aspirations to myth. It is a more dynamic myth, far closer to France in its shifting perspectives, embrace of geometry, and glorious colors—and war ended the movement by exiling Kandinsky from Paris. It is nonetheless as torn by allegiance to the deep past and distant future. The Blue Rider took its name from a painting by Kandinsky, and MoMA owns an even livelier yellow horse vaulting toward mountains. Marc's red cow broods over the entire world.

The scene net shifts to Austria for Egon Schiele and Schiele portraits, Oskar Kokoschka, and a genuinely cosmopolitan eye, but not without its own costs. Kokoschka signs his works OK, but things are definitely not okay. His brooding self-portrait, like the animation of a couple in another portrait, reflects intellectual and cultural activity, but the hands of all three resemble raw meat. Schiele allows pleasure to accompany his lushly decorative women, but with a gilded flatness akin to Art Nouveau wallpaper. Even before the war, however, the movements start to converge on a kind of distressed, pan-European metropolis, like the movie Metropolis by Fritz Lang. In Uprising by Lyonel Feininger, the bourgeoisie and not the working class rises up, strutting like circus performers.

War does come, with Dix at its center. It marks a new vitality for artists like Max Beckmann, who served in the medical corps, but also the beginning of the end. Kirchner, Beckmann, and George Grosz all suffered nervous breakdowns. Kirchner's career ended, although much later, in suicide. Schiele died young of the flu. Even while Käthe Kollwitz debates the political and economic clashes of the 1920s, others turn to close-ups, as if to tune out the nation altogether. By the end, self-portraits by Beckmann in New York and Lovis Corinth look ahead to the more confident and settled expressionist undercurrents of Lucien Freud in years to come.

How German is it?

How German is it? On the one hand, very, or at least Nordic. Those staring faces from 1908 have their antecedent in Edvard Munch his Madonnas and whores, not Pablo Picasso or African masks. No doubt the pessimism has roots in both cultural traditions and the oppressive German state at the turn of the century. It is utterly distinct from the free play of Dada or Italian Futurism with its trust in modernity. Futurists declared nothing more beautiful than the machine, not unlike the giddy populace on both sides that marched off to war, with expectations of victory in a matter of weeks. Grosz hits back at just that with Gott Mit Uns ("God Is with Us")—a corpulent officer with a helmet, a toothpick, and a sneer.

Expressionism embraced tradition, too, in its treatment of women as little more than prostitutes and saints. Dancers have splayed legs and heavy smudges for a woman's crotch, while Grosz serves up more fears of female sexuality in Circe deep kissing a pig. Dix's Nocturnal Apparition from 1924 adds another hooker, amid a decade-long plague of syphilis. Venereal disease or a nervous breakdown, hardly a term still in psychiatric usage, stand for both real fears and a perceived rot in society to its core. That rot just happens to invade even utopia. It also just happens to project itself onto the other, meaning women.

Not even the politics here is all that progressive, and indeed the pastoral traditions in Die Brücke anticipate more dangerous tales of racial purity yet to come. Where Kollwitz—the only major woman artist in the lot—supported democratic socialism, others created posters warning against striking workers. They wanted, like Beckmann, to play the dandy. They wanted to take on some of the middle-class comforts that Beckmann himself had mocked. They wanted order and peace. They were to get the first but not the second.

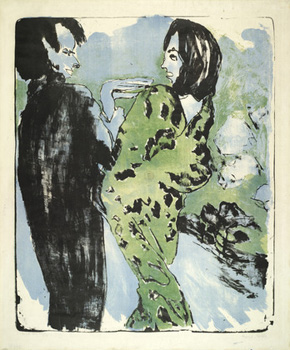

At the same time, parallels to French Modernism are real, and indeed a Viennese photographer, Madame d'Ora, found herself more than at home in Paris. Picasso had his own scary women in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. The pretend woodcuts have their echoes in modernist appropriation of "the primitive." The idylls of Die Brücke have their echoes in Paul Gauguin's longings and escapes. When Emil Nolde prints the same young couple in three different colors, he is closer to Henri Matisse than to Andy Warhol, although in colors so muted and pale that they approach the darkness of the couple's ominous encounter. He and Schiele could almost relish sexuality after all—along with formal experiment and a very modern skepticism when it comes to dogma or appearances.

Religious imagery still appears. It lends a face to authority, with Schmidt-Rotluff's Pharisees, or to suffering, as in Dix's Nun. The terror of a Renaissance crucifixion by Mathias Grünewald lie behind the tense, flattened space of Beckmann's Night, and Jesus's entombment structure his recollection of the dead and wounded. Kollwitz draws on Baroque models to lend sympathy to ordinary lives. What is surprising is how little artists turned to religion at all, just as they could never from the start fully believe their own myths of a purer German spirit. It must no longer have seemed available, as substance or as comfort.

Alternative histories have a way of corresponding to alternative futures. Barr invented his when Cubism's legacy was helping to create what became an Abstract Expressionist New York. Subsequent generations, from Warhol to the appropriation art of the 1980s and then the Young British Artists, needed instead a Modernism emanating from Dada. Right now, such critics as Roberta Smith are finding a return to emotion and substance in sophisticated retreads of folk art, not at all unlike Die Brücke. But does the present really demand a neo-Neo-Expressionism? "The Graphic Impulse" may instead help explain why history keeps circling back.

"German Expressionism: The Graphic Impulse" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through July 11, 2011.