A License to Collect

John Haberin New York City

Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim

The Whitney's Collection: 1900 to 1965

Whatever happened to Stuart Sutcliffe? John Lennon's friend from the Liverpool College of Art quit the Beatles in 1961 to dedicate himself to painting. It might have been the dumbest decision on record, or it may only seem that way because it took his departure for the band to make musical history. But what about his art?

Was Sutcliffe a better painter than a bass player? Has his work survived at all? One might ask much the same (apart from the bass playing) about the Guggenheim's collection or, for that matter, Modernism. Now the museum has a ready answer. It unfolds with an assist from six living artists, as "Artistic License."  Each gets a tier of the rotunda, and each has free rein to choose work from before 1980.

Each gets a tier of the rotunda, and each has free rein to choose work from before 1980.

If you miss the old building on Madison Avenue, the Whitney wants you to feel at home. Works from its collection unfold in a familiar order by movement, from the Ashcan school and the twilight zone of Surrealism to the glory of postwar American art. An opening room, hung salon style on deep blue walls, merely recreates the museum's origins—beside photos of its precursor, the New York Studio Club. One may look to corridors on either side for the realism of Isabel Bishop, Elizabeth Catlett, and Charles Alston or an abstraction by Hedda Stern. Are women and African Americans relegated to the margins to this day? Trust to margins, though, to reframe the center.

Curating against character

Sure, the Guggenheim will always have its Justin K. Thannhauser Collection, with a resplendent portrait by Edouard Manet, newly restored, and no end of Wassily Kandinsky and Kandinsky's late work. Every so often, too, there are hints of more. As "Artistic License" opened, a tower gallery had its holdings of Constantin Brancusi, and work by Robert Mapplethorpe marked a major acquisition. Much on the ramp, too, feels like the dearest of friends. A chrysanthemum in watercolor and ink by Piet Mondrian has its delicacy and precision, and The Nose by Alberto Giacometti still breaks out of its cage. A triptych by Joan Mitchell squeezes into a cubicle along the ramp, whether it will or no.

They are just three in a show of three hundred works, as "Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection." MoMA keeps expanding, and the new Whitney Museum came about in no small part to display its collection, but the Guggenheim rarely gets the chance to look within. Now it can, but through the eyes of others. It also looks to the past, but not in chronological order. It keeps its distance from contemporary art, but from a contemporary point of view. That has to be intriguing, but also suspect.

Why these six guest curators? All, the museum explains, live in New York and know the place well—several from solo exhibitions at the Guggenheim. If that sounds lame, given the city's concentration of artists, the show is as much about the curators as the collection. Each has a theme that has little to do with Modernism's character, origins, and movements. They are fashionable themes at that, contesting the canon. Still, they allow the artists to play against type.

Cai Guo-Qiang selects early work by name artists, as if they, too, were emerging artists today. He hangs them floor to ceiling off the entrance to the ramp— much as his own shallow midcareer retrospective suspended cars and neon over the rotunda. Here, though, the contemporary Chinese artist and Asian new media pay tribute to Western art, with a still-life by Adolph Gottlieb, self-portraits by Arshile Gorky and Franz Kline, a portrait of his sister by Marc Chagall, and Mondrian's chrysanthemum. Cai also brings a flower of his own, in oil on panel, plus four large abstractions. One would make a perfectly credible Mark Rothko, were its colors not a matter of gunpowder and pigment on glass. Yet for once he sees beyond the smoke and mirrors.

Paul Chan looks to a longer tradition, of seascapes and bathers. He is out to rescue its pleasures from sexism and Romanticism. An artist known for disaster images finds a surprising calm, and the artist of The 7 Lights lets back in the light. A dollhouse bath set by Laurie Simmons has the luxuriance of design magazines, and a 1910 ocean view by Mondrian looks as if he had taken it from outer space. Lawrence Weiner sets aside his matters of fact and conceptual puzzles for To the Sea / On the Sea / From the Sea / At the Sea / Bordering the Sea. The words seems to float every which way on canvas.

Richard Prince brings something of his own to the table, too, with works from his collection by Sutcliffe. Their cakey monochrome approaches Jean Dubuffet and Art Brut. They also make a point—that postwar abstraction appeared worldwide, from Gutai in Japan to Tachisme in France, and not just in the United States. Prince treats epic abstraction as a liberation. Art's consummate bad boy and ironist, he has room for such women as Claire Falkenstein and Judit Reigl as well. A work once attributed to Jackson Pollock now looks like a weak imitation, but a genuine Jackson Pollock nearby looks all the better for that.

Call and response

So far, questioning the canon sounds a lot like self-questioning. Now, though, things get deadly serious. Where Prince finds something "uncannily coherent" after world war and the bomb, Julie Mehretu finds "trauma, displacement, and anxiety." Yet she, too, plays against type—against the exhilarating abstract architecture of Mehretu's wall paintings. It takes her to Romare Bearden in Harlem, Philip Guston in moonlight, Francis Bacon at a crucifixion, and a black body print by David Hammons. Even Isamu Noguchi can emit only The Cry.

The darkness deepens with Carrie Mae Weems, who sees everything in black and white. It is not, though, the blackness of race in America. Rather, it is the blackness of a table set for interrogation by Joseph Beuys, torn lead for Richard Serra, and raw earth in photographs by Ana Mendieta. An artist of politics and personal identity, Weems also circles back to subtlety and abstraction. She finds them both in Mondrian and Rothko at the end of their lives. The Soviet art of El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich once again takes flight.

Jenny Holzer brings things to a close with a more open challenge—a floor for women. Yet she drops her crawl screens and outrage in favor of traditional media and shifting meanings.  They include the whites of Agnes Martin along with the multiple self-images of Cindy Sherman. They also center on the theme of "good artists" rather than great white hopes, much as psychology and feminism have championed the good enough mother. Text from Barbara Kruger proclaims itself Not Perfect. With newspapers reduced to their photographs, by Sarah Charlesworth, the text vanishes, and the show comes to an end.

They include the whites of Agnes Martin along with the multiple self-images of Cindy Sherman. They also center on the theme of "good artists" rather than great white hopes, much as psychology and feminism have championed the good enough mother. Text from Barbara Kruger proclaims itself Not Perfect. With newspapers reduced to their photographs, by Sarah Charlesworth, the text vanishes, and the show comes to an end.

After six takes on the collection, could there be more, including yours? Well, obviously, and the show's limits have to call attention to a climate of celebrity artists like the curators—even when they look beyond the limits of their art. It can also call attention to the limits of the Guggenheim. The museum has a world-class collection, but nothing like MoMA or the Whitney. The limits can even undermine the challenge to the canon, as if the neglected were simply not that good. Thank the return of Hilma af Klint, right after her Guggenheim retrospective, and Hilla Rebay, soon after a show about "Creating a Modern Guggenheim," for a reminder that the challenge is overdue.

One can always find new favorites. Robert Morris drapes his black felt over a column of six nails. Its rise and fall has a gentle but stately rhythm. A black airfoil by Martin Puryear soars all the higher by lying on the floor. The long exposures in self-portrait photos by Blythe Bohnen become self-exposures. They pick up on the body traces of Hammons and anticipate a similar obsession in art today. Reflected light in her eyes becomes pencil-thin traces in itself.

It also helps to find such receptive curators. The six worked independently, but their themes come across as call and response—from the twin views of tradition to the twin views of postwar art and the twin views of blackness and women. Louise Nevelson on one tier leads naturally to Louise Bourgeois on the next, just as the show progresses from early to late Mondrian and Rothko. Where Chan begins with Weiner by the sea, Mehretu ends with the blunt frontality and brunt reminder of Weiner's Earth to Earth / Ashes to Ashes / Dust to Dust. Besides, now I know what happened to Stu Sutcliffe, who died unexpectedly of a brain hemorrhage the very next year. And now I know for sure that the Guggenheim has a collection.

In from the margins

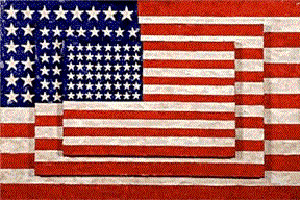

Yes, the Whitney moved to the Meatpacking District to gain room for its holdings, and it took its time finding its way home. It reopened in 2015, with "America Is Hard to See," and it rehung the collection soon enough after, as "Where We Are." Now the fancy titles are gone, and American art through 1965 must speak for itself. Clever pairings, like that of Early Sunday Morning by Edward Hopper with Three Flags by Jasper Johns, are gone, too, although both classics are back. So is Calder's Circus, looking less klutzy and more colorful in a curved vitrine beside more blue walls. Still, the Whitney argues, it has sought the shock of the new all along, starting like Edward Hopper himself in Greenwich Village.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, it insists, was a sculptor as well as patron, and her Studio Club, opened in 1918 (with white walls), anticipates artist collectives and alternative spaces today. The show's opening wall includes women along with George Bellows, and even artists as conservative as Thomas Hart Benton saw themselves as revolutionaries. When John Steuart Curry painted an adult baptism in Kansas, he was observing a religious revival but imagining a rebirth for America. When Florine Stettheimer painted the Statue of Liberty after World War I, she was picturing the nation's entrance onto a world stage—and she remade Lower Manhattan accordingly, landmarks only.  And when Alice Neel created a style for routine portraits today, she was demanding action in the Depression.

And when Alice Neel created a style for routine portraits today, she was demanding action in the Depression.

Even a little diversity can change the rules of the game. Painterly realism includes a buffalo hunt by Horace Pippin, a snowy alternative to stereotypes of African Americans. Both Stettheimer and Neel appear along with the crisp factory realism of Charles Demuth, Charles Sheeler, and Precisionism. Earlier still, photos by Ilse Bing and Margaret Bourke-White (the very first cover for Life magazine) hang beside the West Side Highway for Andreas Feininger. Marisol, born to Venezuelan parents in Paris, claims Pop Art for women with her boxy wood figures—while Rosalyn Drexler rather than Andy Warhol paints Marilyn Monroe. The Rose by Jay DeFeo and a white shroud by Norman Lewis hang between Franz Kline in mostly black and Joan Mitchell in mostly white.

For starters, they are changing the rules for others. A wall reprises the Whitney's "Real/Surreal" in 2012, but it faces a 1939 film by Mary Ellen Bute that looks more like today's animation. DeFeo and Lewis bring out the black and white in color-field painting—although colors return in "Spilling Over" just a floor away. Marilyn Pursued by Death brings out the death instinct in Pop Art, even before cigarettes and a colossal hamburger for Tom Wesselman. And yet their context changes the rules for them, too. DeFeo's one-ton accretion becomes an exemplar of expressionism, rather than of Bay Area art or the bodily discomforts of Post-Minimalism.

Three artists have alcoves of their own, including a black and a woman. Remember the "triumph of American painting"? Jacob Lawrence in tempera sees anything but a victory, even in 1947. His War Series shows the anonymity of massed soldiers, the loneliness of the letter home after a death in combat, and a head sunk as if for good in prayer. Georgia O'Keeffe paints music and a skull as if they were one—but then Hopper could change the rules, too. His naked wife facing the sun is not a virgin at the Annunciation, but a woman at seventy-eight who has known sex and death.

As so often, Hopper's light belongs to the early hours or sunset. The longest moments in his art depict transience. The collection may look much the same as ever, but the curators, David Breslin with Margaret Kross and Roxanne Smith, see continual change. The show ends where it began, with a mobile by Alexander Calder—but also with a single work of contemporary art. An entire wall of mirrored panels by Nick Mauss turn its back on the collection, even as its stains extend Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. Facing the terrace, it also reflects the city.

"Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection" ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through January 12, 2020. The Whitney Museum of American Art rehung its collection in June 2019.