The Question of Women

John Haberin New York City

Mira Schor and Anna Ostoya

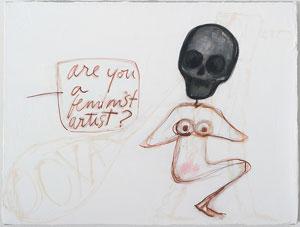

Are you a feminist artist? Mira Schor wants to know—and so, I trust, will you.

Is it a matter of persistence, for all the obstacles, or does it involve taking that as your theme? Is it about images of women, in all honesty, or about interrogating images of women, in all their frequent dishonesty? Of course, it can mean all of that and more, and much of the strength of feminism in and out of art is its divisions and diversity. Schor works with the possibilities, too, in both text and images, even turning them on herself. A look back to her emergence as an artist shows the honesty and even poetry of her self-assertion. Meanwhile Anna Ostoya settles for the next best thing, with an assist from art history—taking revenge.

Death knocks

You may not associate Mira Schor with installation art, but her latest series cries out to be seen as a whole. Its standing figures, one to a sheet, keep coming until they exhaust the walls. I cannot swear that all of them are women, although practically all have circles for breasts, in a charred red over black ink. I cannot swear which are dead or alive. (Talk about zombie formalism.) They do, though, carry an insistent humanity—and a question.

are you a feminist artist? The question appears throughout, in cursive and in lowercase, except where it does not. Other sheets may bear something more vulgar or more pleading instead, and others may show nothing at all except their poor, bare forked animal. Well, not quite bare, for they approach stick figures except for hints of a dress or smock, and part of their feminism is a refusal to disrobe for anyone's pleasure. And yet it is hard to say whether the question is directed at you or at them. If it is their question, it could well be directed at themselves.

It could encompass, too, their claim as an artist as well as a feminist. Schor calls them Power figures, like the African art that she cites as an influence, although part of their power lies in enduring the status that she identified in an earlier essay, "On Failure and Anonymity." They hold their arms close, like trained boxers, or read rather than paint. Still, they gain in power by coming together. They also benefit from the broad space of the gallery's back room, into which one must step down a foot or two. Sure enough, one might be entering an installation.

The artist might object to that thought, in an art so obviously handmade. Acrylic and ink align the series with both painting and drawing, while the sheets of tracing paper evoke the scale of one and the fragile basis of the other. Maybe you associate installations with macho gestures or big money, trash art or empty rooms—precisely what she is happy to confront. Still, the author of A Decade of Negative Thinking has room for self-doubt. In a show called "Death Is a Conceptual Artist," conceptual art may be the death of painting, or it may have the last word. Schor is known for text art, and a painting up front includes the single word language.

The front room introduces her strategies as a whole. Paintings can approach flesh tones, and one consists entirely of the word flesh. Others introduce her figures, with their circles for breasts, a skull or mask for a head, and in one a crescent moon for hair. They may appear outspoken or introspective, balanced between an open book and a flower. They may have their lips sewn shut, or their gaze may train on its object with laser eyes. Two emerge in burning orange from a thick field of black—perhaps what one of the Power drawings means by the word chaos.

Text aside, Schor works in a tradition in which crusty, stabbing figures stand for agony, outrage, or a carnival. She comports with others who cannot stop for death, like Ida Applebroog, Joan Semmel, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Nancy Spero, Leon Golub, and James Ensor—even if personally I am not all that comfortable with any of them. If feminism makes you think first of a lecture, she has appeared in "#class," a splendid assault on art institutions curated by Jennifer Dalton and William Powhida. Still, her painterly surfaces and firm gestures refuse to go away, and so do the questions. Is the work angry, despairing, or just plain funny? You bet.

A bear of an MFA

As a student at CalArts, Schor found herself in a strange landscape. It could hardly have been otherwise for a New Yorker in California, and she marveled at its sunlight and vegetation. It could hardly be otherwise, too, for a woman in 1972, wrapping up her MFA and pondering her future. In her "California Paintings," she is on the threshold of a world filled with cypress trees, tall grass, wild animals, and long sunsets. She is also on the threshold of a dream. Still, she is dreaming with wide open eyes.

Once she does lie in bed, while her naked self below faces a clothed man. Both press toward their encounter, and both draw back—she behind a tree and he by covering his face. Both are also walking their cats, which adopt a calmer pose than animal instincts would suggest, perhaps out of ancient statuary. Elsewhere she has a wall to cross or to protect her, but with the outdoors straight ahead. Floor tiles to either side of the wall approach two-point perspective, and two moons have risen side by side, one a crescent and one full. Schor has decisions to make and choices at hand, but as an artist she is defining them, too.

She is also defining herself as a feminist, and she took part in the Feminist Art Program back then with Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, still an influence on Clarity Haynes. Maybe you associate the program with dead certainty—the certainty of self-assertion for supporters or of "political correctness" for conservatives. Maybe, too, you associate Schor with her Power figures, with all their jagged edges, cutting sense of humor, and closeness to death. Here, though, she takes uncertainty as part of her identity as a woman, too. These may be paintings, but they are works on paper, too. She is trying things on, including roles and women's shoes.

They are predominantly gouache, with warm colors and crystal clear drawing. Many display together, like a sketchbook still in progress. Men are infrequent at best and hilarious. She dances on the back of one as he morphs into or out of a wild boar. She also encounters a black bear—feeling each other out with one arm or paw, then back at a distance, and at last wrapped passionately or dangerously in a bear hug. Cats, dogs, and two versions of her wading in water surround a stranded automobile, because how do men get us all into these messes anyway?

Not that certainty is a bad thing, when a woman's life and women's rights are at stake. One should not overlook the certainties either amid the humor and the poetry. A title, in French, speaks of the dampness of night without a single caress—because her existence apart from a man's caress matters as much as the tropical loneliness. Even two versions of herself face off in a single sketch, they may have bloody hands. Labels on one sketch identify her black hair as a shelter but also, as matters for an artist, her brain and her eyes. Her crotch and armpits are shelters for her cold hands, but then her cold hands are shelters, too.

Can both hold true? Art still has its way of exceeding certainties. It also has a way of exceeding student work, and much of hers has not displayed in public, if ever, since 1973. I, for one, am tired of budding artists with the stamp of approval of select schools—or the aura of John Baldessari, the conceptual artist who taught at CalArts in those years. The show's lesson might be not to try this yourself at home or in a gallery unless, like Schor, you intend to graduate and to move on. Still, it is as undeniable as a bear hug and as hard to forget.

Judith: the video game

Under x-rays, Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi becomes a virtual machine of torture and violence. Its colors vanish, from the deep red of the victim's robe to the blood dripping down his sheets, echoed in the sleeves of both Judith and her servant. The gleam of her sword gives way to a different chill in the pallor of black and white. Gentileschi had toyed with different placements for the dying man's arms, right on canvas, and x-rays reveal them all, layering one plane upon another. The eye of the scientist or restorer becomes as focused and clinical as the avengers. It could be a disturbing metaphor for art history.

It suggests a Cubism for today, without the macho swagger of Pablo Picasso. It presents women as actors, quite apart from the brothel scene of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. It adds hard edges and multiple copies suited to a digital age. It also prefigures Anna Ostoya. She slices and dices Gentileschi across a gallery's four walls. The very presentation has a Cubist side, with large canvases interrupted by smaller ones riding up the wall and down.

It suggests a Cubism for today, without the macho swagger of Pablo Picasso. It presents women as actors, quite apart from the brothel scene of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. It adds hard edges and multiple copies suited to a digital age. It also prefigures Anna Ostoya. She slices and dices Gentileschi across a gallery's four walls. The very presentation has a Cubist side, with large canvases interrupted by smaller ones riding up the wall and down.

Gentileschi was taking her own revenge. Her Judith in the Uffizi has become canonical, although the Book of Judith, omitted from the Bible, has not. Yet it needed multiple attempts and multiple sources to exist. She would have known Judith as an emblem of civic pride from the sculpture by Donatello, designed to stand in a public square in Florence. The sculpture even bears a civic message on its base: "kingdoms fall through luxury, cities rise through virtues."

For Gentileschi, the message was not just doctrinal but personal. A lost early version probably copied closely a painting by her father, Orazio. There the deed is already done, and the women look away in caution and fear. Another version, in Naples from around 1613, coincides with her rape trial against her teacher and her maturity in art. She has set aside her and Judith's fears, just as she has taken away any show of sympathy for the victim's pain or of strength in the victim's arms. It riffs on a painting by Caravaggio from around 1599, with the head of Holofernes at its center in all its horror and pain and the maid in profile as a she-devil (or, quite possibly, a later copy in Naples closer to her own)—but with all three figures at its center, in a single whirl of violence.

The Uffizi version, from 1620, changes neither Judith's pose nor the dead man's eyes. It only sets them in a deeper and darker space, both psychologically and on a larger canvas. Nothing in the galleries here can come close to matching it. Ostoya's cartoon vision gains interest only slowly, as one takes in the room of copies without an original. The drips of blood add up, while the passion ratchets down. Heroine and villain become more distant, but also more alike.

They also serve as a prelude to a second room—and a turn to black and white, like an x-ray. There a second series, Slain Trances, has the further multiplicity and added jolts of photo collage. Two of the small images insert Ostoya's face as a teen, fearful or confident, while others reverse the gender of their actors. Still others adopt the symmetry of reflections out of tantric art, while collage quotes extend to African art and, sure enough, Picasso. The entirety comes close to trivializing Gentileschi or Cubism, like an extended video game. Yet it helps with the puzzle of what makes past art at once familiar, unfamiliar, and alive.

Mira Schor ran at Lyles & King through April 24, 2016, and May 19, 2019. Anna Ostoya ran at Bortolami through April 23, 2016.