A Woman's Bodies

John Haberin New York City

Joan Semmel, Marilyn Minter, and Leonor Fini

In one important version of feminist art, a woman must reclaim her body and her autonomy from the male gaze. For Joan Semmel, the next step is to reclaim it from her own. Semmel's paintings double it, on the way to a more unified vision in the face of age. Does that make her a realist? And what about Marilyn Minter, in painting and video that start with photographs—or Leonor Fini at the Museum of Sex in Surrealism?

Not every museum retrospective comes with multiple warning labels about adult content, but then not every retrospective includes a commission for Playboy. Marilyn Minter welcomes comparisons of art to pornography, but on her own terms. The opening wall text at the Brooklyn Museum says that she plays on "our deepest impulses, compulsions, and fantasies." Really, I wanted to reply, speak for yourself.  And so she does, emphatically. Like the warning labels, she is out to lure you in and to turn you away. Decades earlier, Fini welcomed adult audiences of both sexes, but with compulsions and fantasies all her own.

And so she does, emphatically. Like the warning labels, she is out to lure you in and to turn you away. Decades earlier, Fini welcomed adult audiences of both sexes, but with compulsions and fantasies all her own.

Two views of aging

If you are like me, you have trouble approaching Joan Semmel. You think you know her by now, and you know all too well what to expect. You expect a display of skill, from an artist on intimate terms with portraiture, anatomy, and her own flesh. You expect an unblinking frankness, from a woman in her eighties willing to confront the harsh toll of age. You expect a certain self-obsession, because she takes art and the body as her subject. You know her filling a canvas and then some.

Once again she rewards those expectations, as recent crossovers between abstraction and a woman's self-portrait never could. She is literally baring herself. And once again she accepts the limits of realism, long after art began to link honesty not to the truth in painting, but to skepticism. She portrays herself as vividly three dimensional, but also up against the picture plane and at alarming angles. You know by now to associate that defiance of convention with Mannerism or expressionism—further markers of physical and emotional pain. You expect it to earn extra credit for defying sexism and ageism as well.

Still, you might have to look again. She is not striving for photorealism, whether in the atomization of its subject for Chuck Close or the Neo-Mannerism of Philip Pearlstein. Nor is she at the opposite extreme, with twisted features as an obvious emblem of revulsion for Lucien Freud or Francis Bacon. She does not spend much time on her crotch and public hair, unlike Betty Tompkins. She has even less in common with what has become a kind of official style for American realism, after Alice Neel—with breezy gestures and colors skating over an apparent concern for the individual. She is just going about her business, she seems to say, with pleasure.

I admit to finding all these versions of realism a little too easy, much as with fleshy portraits by Clarity Haynes, including much of her own past work. (Perhaps I can accept detail and gesture more easily in landscape, where they correspond to the limits of sight.) They can look even less relevant now that abstraction and realism so often blend together. Semmel, though, is also defying expectations. She may throw an arm across her face, as if in shame. She may cut off her face, as if in agony, but her features, when they appear, look calm and measured.

They also leave much of the action to her breasts and lower body. They come off not as disfigured, as for Aneta Grzeszykowska, but proud, monumental, and even sexy. If that sounds like still another version of politically correct, there, too, she plays against stereotype. More than before, she seems to be searching for herself rather than sending a message. How can someone in those poses simultaneously observe herself? And where exactly is she?

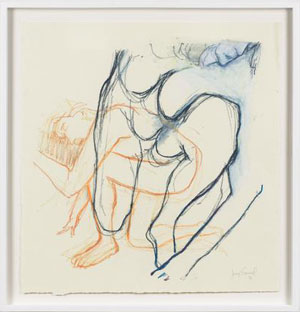

Most of her latest paintings or works on paper combine two images, one in bare outline and one in full. They play off against one another, as two views of the self, or combine into a single elusive body. They also bring out the display of painting for its own sake, in the translucency of oil and oil crayon. Colors run from flesh tones to exaggerated yellow, pink, and blue. She still sees self-portraiture as feminist, much as for Mira Schor—and the aging naked body as a means "to fully experience our common humanity." At her best, that common humanity will always lie first and foremost in paint.

Obscure objects of desire

Marilyn Minter has invited outrage since long before that Playboy series of women shaving their pubic hair, Plush from 2014. At first, she did so less wittingly, much like Cathy Wilkes. Photographs in black and white from 1969 show her mother at her make-up mirror and in bed, smoking. They evoke a southern belle out of Tennessee Williams and, more subtly, a real woman's descent into alcohol and addiction. They scandalized fellow students with, no doubt, a very different ideal of femininity, mothering, and the old South. They look ahead to Cindy Sherman as well, but this is not a pose.

Not yet, at least. By 1989 Minter is painting after images of food torn from commercial art and, soon after, images of women torn from porn magazines. Both series have their share of stand-ins for an erect penis, and both allow women to use their tongue. By the mid-1990s, though, she is staging scenes herself. She is also teasing an audience more likely to be watching adult content than reading art criticism—with a commercial for late-night TV, showing her at work. An ad for a proper art magazine, she observes, would have cost about as much.

Not yet, at least. By 1989 Minter is painting after images of food torn from commercial art and, soon after, images of women torn from porn magazines. Both series have their share of stand-ins for an erect penis, and both allow women to use their tongue. By the mid-1990s, though, she is staging scenes herself. She is also teasing an audience more likely to be watching adult content than reading art criticism—with a commercial for late-night TV, showing her at work. An ad for a proper art magazine, she observes, would have cost about as much.

Since then, she has taken naked flesh to a larger and larger scale, temptations and blemishes intact. Food porn gives way to the disgust and allure of caviar, vodka, and liquid candy dripping in and from a woman's mouth. As one title has it, she is having a Meltdown. In her latest on the Lower East Side, women appear ever so close to the picture plane but behind glass. Drops of water on the glass have the sparkle of photorealism. They assert both immediacy and distance, and both are alluring but also unnerving.

Minter's technique asserts much the same. Her first paintings already push at once toward photorealism and abstraction. They also introduce tactile sensation, liquids, food, and disgust—with splashes on linoleum or frozen peas in a sink. These days, she photographs models, creates a montage, blurs or heightens it in Photoshop, and renders it in enamel on metal, with ample help from studio assistants. She may draw over the top with her finger, like graffiti as finger food. One can hardly get more engagement or more distance.

Born in 1948, she grew up in Louisiana and then Florida, but she is playing with a very urban sophistication. The Brooklyn Museum has shocked defenders of moral values before, with the Madonna in elephant poop by Chris Ofili and with work in its collection by Robert Mapplethorpe. Minter made the show's final slow-motion video for the museum's 2014 exhibition of "Killer Heels," although the motif also appeared in the 2006 Whitney Biennial. She is in a line of women artists exposing themselves or others—including Sherman, Semmel, Betty Tompkins, Carolee Schneemann, and Marina Abramovic. When she asks why women cannot "own our bodies," she is speaking the language of feminism, but can feminism apply to the tawdry antics of media celebrities? She can only hope, as the title of her retrospective has it, that it is all "Pretty/Dirty."

Is that enough to respond to outrage—including the outrage of those who see only glossy, demeaning, and painfully obvious images of women? Does it change anything that these fragmented images are from a woman's hand? Maybe not, not even when Minter's chilly, silvery heels splash in water as if taking a hammer to the male gaze. One can, though, start to appreciate the layers of temptation and distance. She calls a painting Private Eye, with a play on a woman's point of view and private parts. For once, in an all too explicit art, it is a proudly obscure object of desire.

Sex as surreal

If you are ever tempted to think of your sex life as a trifle surreal, you have nothing on Leonor Fini and Surrealism. In a movement devoted (in the words of John Russell) to the dominion of the dream, she made her art not of nightmares but of desire. And she claimed a desire for sex and self-sufficiency for a woman. An early self-portrait as Femme Rose still owes more to Symbolism or to Pablo Picasso and his Blue or Rose Period. Yet it places her at full length, front and center, with her breasts visible through her delicate robe, but with the harlequin's costume thrown open only for the fullness of her belly. She controls what a man or woman may see, and she contains multitudes.

I lived five years above a topless bar and never once went in, and I never dreamed that I would enter the Museum of Sex now a few blocks away. Here, though, the museum of naughty bits takes on a retrospective spanning forty years of modern art—if, like Fini's art, on its own terms. Subtitled "Theatre of Desire," it plays out against lowered lights and piano music, somewhere between a dreamscape and a bordello. Fini might have appreciated it, given the theatricality of her painting and the diversity of her achievement. She also wrote fiction, illustrated Charles Baudelaire and the Marquis de Sade, designed costumes for the dance and theater, appeared in Life magazine with a Devil-Cat, and posed in performance for such photographers as Carl Van Vechten and Henri Cartier-Bresson. She created a large armoire with women on its face, their bodies for its curves, and their navels for handles.

Not that she settles for temptation, nurturing, or even dominance. She does paint herself in the 1930s with wild hair, body-tight black armor, and, in one instance, a red scarf out of a Renaissance portrait by Jan van Eyck. She also uses a sleeping male nude as a tabletop. He is still, though, a full figure and an object of desire, even when he lies amid yellowed leaves and the architectural ruins of a cornice. And then she leads a man, his red robe wide open, into a landscape. She is introducing him to something larger and stranger, while also introducing herself.

Fini's choice of Baudelaire's Les Fleurs de Mal, de Sade, and the Satyricon says a lot about her tastes, but she also entered fully into Surrealism and a Surrealism beyond borders. Born in 1907 in Argentina and raised in Trieste, in Italy, she moved as an aspiring artist to Paris. She knew René Magritte and Man Ray, found encouragement in André Breton, exhibited with the movement at MoMA in 1936, and had a push toward the dark side from Georges Bataille. She flirted after 1958 with near abstract surfaces between minerals and forests after Yves Tanguy. She is closer still, though, to a slightly better known woman, Leonora Carrington in Mexico and England.

She amounts to a kinkier version of Carrington, with a touch of the self-presentation of another woman in Mexico, Frida Kahlo. After the hard-edged self-portraits from the 1930s, though, she gains from opening her world to men, even while defining the kind of man she wanted in her life—thoughtful, theatrical, sensual, and open. A man in the 1960s still sports peacock feathers. She gains, too, from her immersion in so many media. They allow her a public and a private side, even as her performances involve desire and her desires are way over the top. A gold cape as a costume from 1965 embodies both.

Her late work turns on a larger scale to mute colors, light shading, clear but soft outlines, indefinite space, alchemy, and witchcraft. She no longer appears in person, but she aspires that much more to myth. Hecate's Crossroads places more than one sorceress in a labyrinth, with a red ball in place of an apple as a temptation at its center. She transforms bathers for Henri Matisse and the male gaze into active swimmers and dreamers, while a younger woman as The Pearl lets her robe fall to her feet. A wiry suite of drawings gets kinkier still, with a gynecological exam and The Council of Love. She clung to Surrealism decades after its prime, almost to her death in 1996, but she had dedicated her life to excess.

Joan Semmel ran at Alexander Gray through October 15, 2016, Marilyn Minter at Salon 94 Bowery through December 22, 2016, and at The Brooklyn Museum through May 7, 2017, and Leonor Fini at the Museum of Sex through March 4, 2019. A related review looks at Minter in 2005.