No End in Site

John Haberin New York City

But what's weird is how I started to think about chance. . . . I had just seen movies that left nothing to chance, and when I went out I had found contingency. It was the necessity of film that made me feel that there is no necessity on the street.

— Jean-Paul Sartre

Nonsite from Smithson to New Media

Robert Smithson liked deductive logic and formal systems well enough, so long as others took care of them. His spiral of earth, slowly sinking into the Great Salt Lake, could almost undermine a Sol LeWitt wall drawing. But had he foreseen a digital universe, would he ever have entered the gallery?

Nonsite as rupture

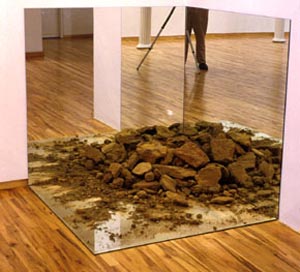

Smithson did enter the gallery, of course, where his work has a notably low-tech and strikingly physical presence—even in the mirror. His Enantiomorphic Chambers, like his arrays of mirrors amid salt and rubble, could almost make a mockery of conceptual art. As for fancier algorithms underlying digital art now, better bury them with an old-fashioned steam shovel before they get out of hand.

It takes chance, in the collision of millions upon millions of molecules, to produce his beloved entropy and the arrow of time. It takes a serious rupture of gallery and museum walls to create earthworks, the mark of the creative artist on the landscape. It takes a more subtle breach to invent nonsites, the presence of the landscape within a gallery—in the case of Sabine Hornig, an urban landscape. It takes a certain permeability between artist, object, nature, and human history to suffer either then to take its course. Spiral Jetty now makes its reappearance from time to time after many years underwater, and I hardly know whether to thank happenstance, patterns of water use, or global warming.

For those more attached to round numbers, however, Robert Smithson would have turned seventy with the new year—or, more exactly, January 2. (The law of large numbers means some slippage.) He will have died thirty-five years ago this July. Gordon Matta-Clark, another site-specific artist who labored hard to destroy a site, was born and died precisely five years after him. Both also had retrospectives in the last three years, at the very same New York museum, and it might disappoint them both to spot a trend, rather than mere coincidence. Sites and nonsites are where the action is.

When MoMA reopened in 2004, it displayed the film of Smithson's Spiral Jetty. When the Met added a small gallery for contemporary photography in 2007, it included Matta-Clark. Worse for those who insist on sites as open communities, their Whitney retrospectives came with a sense of closure. A pier that Matta-Clark illegally helped dismantle is giving way to more space for salmon and a park along the Hudson. The Floating Island that Smithson planned, a barge of still more rubble, circled Manhattan. More to the point, their influence is everywhere.

New-media artists might like to think they have set the paradigm for nonsites. They could even have the copyright, give or take open source code. One speaks of a Web page as a site, but as traces of elsewhere, distributed across many networks. An elsewhere that leaves cookies on one's "home" computer makes an even better model for a nonsite. Like Christina McPhee in her videos and digital prints, artists have used also geologic and other data to represent landscape—both online and in the interior of a gallery. In this way, the facticity of real time becomes a potent metaphor for the representation of real space.

Why the sudden revival of two late artists devoted to site and nonsite? Why the interest in a couple of fragmentary careers devoted to leaving fragmentary evidence, with another show of "Feminism and Land Art" to come? One can explore just that, without privileging information technology and new media. I shall focus on what has changed since Smithson and Matta-Clark, in order to get at reasonable criticism of site and nonsite for art today. I shall argue that it helps pinpoint additional reasons for the terms' relevance.

Nonsite as influence

I started with Smithson and Matta-Clark as paradigms of site and nonsite. But why worry about them in the first place—other than as a deliberate affront to cutting-edge digital artists?

For starters, their influence extends well beyond virtual reality, to an increasing range of options subsumed under site and nonsite. If the litany seems all too familiar, it should already get one asking what has changed in the conditions surrounding the making of art. Consider the scope of big shows from 2007 alone.

Their influence includes art that restages the outdoors indoors—invariably in a state of incompletion, fragmentation, or deterioration. Museum-scale group exhibitions suggest a culture-wide obsession, as with "Undone" at the Whitney at Altria, followed in no time by "Unmonumental" at the New Museum. Their influence also includes semi-fictional recreations of an artist's private environment in the space of a gallery, such as Friedrich Kunath at Andrea Rosen, Rirkrit Tiravanija dishing out curry (yes, yet again) at David Zwirner, or a cordoned-off memorial there to Jason Rhoades's living room soon after. Museums, too, have embraced the theme, with Pipilotti Rist in a summer group show at the Guggenheim and Beth Campbell at the Whitney.

It includes any number of artists dedicated to trashing the joint big time. Ironically, any record of the disastrous run-in with Christoph Büchel has vanished from MASS MoCA's Web site. At the same time, galleries and museums have shown more willingness to sponsor off-site transformations, as when Roxy Paine plants his steel trees in New York City parks.

In all these works, one should not see site and nonsite as an opposition of the human hand and nature's, because the landscape under deconstruction is a human one, too—just as with Smithson's Buried Woodshed or Matta-Clark's Building Cuts. When Urs Fischer broke right through a gallery floor into a hidden New York this fall, he discovered a Manhattan built more on sand and thus probably landfill than on bedrock. When Mike Nelson staged an abandoned Essex Street food market as A Psychic Vacuum, he competed with an active market across the street, but he brought his own tools and some of his own dust.

Arthur C. Danto called his essay on Peter Fischli and David Weiss "The Artist as Prime Mover." He thus pointed to their dual role as omnipotent creators and as absent from the creation. One does not usually think of their fabulous Rube Goldberg contraption on film as a site or nonsite, but their work's ambiguity underlies every use of the terms. One reason, then, for a continued influence is how productive it has proved to be. Next I shall offer a couple more reasons, even closer to platitudes. One had better get the good news out of the way fast.

Nonsite as recovery

At the very least, then, no one is getting rid of surprisingly nostalgic, even trashy conceptions of site and nonsite, not even by going online. Site-specific installations and dislocation have become so established that the Whitney even builds the 2008 Biennial on them. It may not have much to do with the under-the-radar approach of Smithson and Matta-Clark, but people who buried buildings or blasted through the roof made some pretty bold gestures, too.

What accounts for the resurgent interest in two artists and two entangled ideas? Most obviously, it amounts to the usual generational swings, as yet another age cohort enters the museum. After Neo-Expressionism and irony, it has become safe to return to the past, provided it comes without the old narratives of formalism and theater. In 2007, too, for example, David Reed curated a view of the late 1960s and early 1970s as "High Times, Hard Times," and here, too, painting spilled over into real space. A year earlier, MoMA devoted the atrium to Jennifer Bartlett and Bartlett's Rhapsody as another study in how painting refused to die. Minimalism is fine now, honest, so long as comes with a warm narrative of survival—and reasonably warm, fluid work to match.

Conversely, the themes never really began with Smithson and Matta-Clark, and they never went away. One can see their presence in the litany of recent exhibitions, or one can look back in time instead. Postmodernism has seen disruptions of art as self-contained cultural artifact in everything from Dada to Walter Benjamin's Arcades. Even the idealism of Le Corbusier's buildings surrounded by park, like Olmsted's Central Park, invites human habits and landscape to fight it out for themselves.

Besides, if Modernism sounds too utopian these days, one should not overlook the late-1960s optimism in Smithson and Matta-Clark. Both recover contested sites for artists and others on the economic margins. Both also have a heck of a time doing it.

For all that, something has changed. One can see it in the almost ridiculous explosion for 2007 alone. Another purported use of real-time data, by the Brooklyn duo Fame Theory, displays career prospects numerically on LED, like a pretend stock ticker. One can see it, too, from how fixed notions of temporal continuity and discontinuity have already entered an account of site and nonsite. One recovers nonsites in installations today as if recovering the past. In the process, one recovers conceptual boundaries all over again, even when one thought one had broken through the walls.

I want therefore to consider next alternatives to nonsites as blissfully marching on or in need of recovery. Museums sometimes like art history that way, and the scenario has real power. However, I shall take up challenges to so optimistic a scenario. Maybe the ruptures that nonsites and earthworks thought that they had earned have lost some of their ability to disrupt.

Nonsite as fashion trend

Nonsite and site-specific art call in question distinctions critical to traditional definitions of art. As so many have insisted, these include the distinctions between process and product, the art object and its destruction, artist and audience, nature and culture, and the gallery as opposed to locations not so uniquely devoted to experiencing or selling art. And again, this critique has continued relevance—and not just to digital media. It acts itself out through prestigious works, installations, and institutions now. When Exit Art reopened on Tenth Avenue in 2003 the same day as artists set to work, with "The Reconstruction," it was asking where the work of art ends and the art institution begins. Not quite five years later, the arrow of time has become art's fashion trend.

That overwhelming presence, however, points to a problem that has faced every version of Modernism or Postmodernism: what sustains a critique—especially a political or historical critique couched in relatively abstract terms of sculpture, time, and space? Has Modernism failed? Either it succeeds or it fails, and either way it loses its relevance and stands marked by failure. The paradox of art after the end of art, with higher and higher prices, has itself become a cliché. Yet it is also a seriously unfair cliché, since failure presupposes art as goal directed, with millenarian goals.

One such familiar complaint about contemporary art, by Suzi Gablik, ends in an explicit plea for transcendent values. I keep returning to art, like to philosophy, without expecting any. However, the notions of site and nonsite run into particular dilemmas. These parallel the paradox surrounding a temporal disruption: the new terms mark a rupture in the gallery walls, one in turn predicated on their existence in the first place. The growth of noisy, pricey installations shows the limits of that assumption now. When digital artists such as John F. Simon, Jr., or Casey Reas make some of their best work available free online, they can seem less like pioneers than a rearguard action.

First, nonsite becomes less disruptive once galleries have learned to absorb anything—and the more the better. How better to legitimize the artist as mythmaker than by creative destruction of a gallery? How better to grab the viewer hesitating between the hundreds of Chelsea galleries than by literally and figuratively making a scene? How better to create enough art objects to keep up with the market? Second, galleries and museums now also routinely sponsor earthworks and other art off-site, from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council to Dia in America's south and west. Third, galleries have become less a site than a venue in global markets, with multinational locations, online images, and booths in the almost unending art fairs, one with a critic, Christian Viveros-Fauné, as curator.

New media can partake of all these. It brings remote images and new physical materials into galleries, extends a gallery's sponsorship elsewhere, and makes both an emblem of the age of globalization. When Emily Jacir projects convenience stores in the Middle East and America side by side, or when Chen Chieh-Jen populates abandoned factories in Taiwan, they make globalization explicit. It also has even less resemblance to Smithson's geometric bins for rubble too heavy for individuals to break. Not coincidentally, video is aspiring to higher and higher production values. I, for one, found it disconcerting when the black refugees washed up on shore in a new video by Isaac Julien seemed to belong to the bright colors, high definition, open vistas, and languorous pace of a commercial for European travel.

I do not mean that the vision of Jean Baudrillard—itself too apocalyptic and too reassuringly a closed ending—has come true, even if a world of images has appeal for new media. If anything, the art object has returned with a vengeance. Nor do I mean that art has sold out to commodity culture. Rather, capitalism, artists, and new media are all powerful agents of transformation, and when they happen to work simultaneously, things get hairy. Once a gallery extends everywhere and nowhere, then, has the concept of nonsite found its fulfillment, or has the distinction between site and nonsite simply gone out the window? Or has the question itself given the concept new relevance?

Nonsite as the site of anxieties

While the contemporary practices of such artists as Susan Philipsz and Jan Tichy reflect the urgency of site-specific art and nonsite, then, there is simultaneously an erosion of distinctions between them. Moreover, while the erosion stems in part from some forgettable art, it is also part of a greater breakdown in definitions. It has to do with the impossibility right now of clearly distinct art movements like those of early Modernism, leaving what Jerry Saltz has called a superparadigm. It can also make Smithson's native optimism or Matta-Clark's instinct for rebellion seem naive.

Fortunately, however, art thrives on anxiety as much as optimism. The influence of site-specific art and nonsite has grown not only because the market likes them, but also because artists are tapping into anxieties. Each challenge noted so far carries anxieties—not refuting artistic practices, but rather making them a site of cultural engagement. A gallery's claims to encompass other sites match anxieties about the art market. The proliferation of such sites matches anxieties about the loss of an American wilderness. Globalization carries enough anxieties of its own as well, like an assembly line in Colombia for Oscar Murillo or the shipping industry for James Benning and Peter Hutton. The Web comes with anxieties about privacy, the meaning of community (or "friends"), and the maintenance of Net neutrality.

The return to the 1960s with which I began reflects still other anxieties. Part is politics in the age of Bush, with the culture wars raging perhaps one last time, as in the Whitney's "Summer of Love." Part, too, is how gentrification, preservation, and the hole at Ground Zero have given the city as site and nonsite a new social history. Matta-Clark's pier fell, but the High Line will stay put. Smithson's homage to Passaic may seem less ugly or quaint in face of anxieties about suburb and sprawltown. Naturally both took up new media as a record of process—before, of course, personal computers.

The anxieties of site and nonsite evolved even in Smithson's and Matta-Clark's lifetimes. It can in fact seem trumped up to think of them together. Smithson has a kind of iconic status for Minimalism, both as artist and theorist. Matta-Clark could stand for Post-Minimalism, as a rebel and a doer. Smithson offers a counter to Modernism's history of real and ideal cities, with paeans to the blankness of Sixth Avenue. Matta-Clark immerses himself instead in changing residential patterns of New York and New Jersey.

On film, Smithson seems to be discovering the landscape along with the camera. Matta-Clark seems to delight in leaving the mark of his body on a building or in a Tree Dance. In these ways, he has begun the evolution of nonsite from an artistic event to a social structure and a personal history. Installations have broken out in part because the three came to seem newly relevant and newly intertwined. Nonsite still carries a residual idealism, like the other inspired by Hegel, but simulacra did not put an end to anxieties about death and physical decay. They just went on display in galleries, like the cellars of Paris in photos by Matta-Clark.

American art may seem more like mass entertainment now, if perhaps only in New York, Los Angeles, and Miami. More precisely, artists are having to navigate between celebrity and irrelevance. New media are navigating between temptations, too. They can yield authority to images, or they can claim authority for data as representation. They can claim a monopoly on contingency, the very kind that Sartre found not on screen, but on the street. Or they can give new meaning to the anxious object.

This article began as contributions to "Stations, Sites and Volatile Landscapes"—an invited discussion curated by Christina McPhee on Empyre, a "global community" devoted to "cross-disciplinary issues, practices, and events in networked media." The epigraph derives from Simone de Beauvoir, "Conversations with Jean-Paul Sartre (1974)," in La Cérémonie des Adieux, my translation.