All Over Again

John Haberin New York City

Jackie Saccoccio, Stephen Maine, and Abstraction

Keltie Ferris, McArthur Binion, and Daniel Hesidence

Now that painting is back from the dead, an awful lot of paint is getting flung around. Mind if I say too much?

Maybe it goes without saying, in an art scene with too much of everything. Alongside the big, half-ironic gestures celebrated by big galleries and the Museum of Modern Art are the many sincere gestures in smaller galleries or under the radar. And it takes more than a sincere commitment to paint to produce a painting. Thankfully, some artists have found a way to embrace both detachment and commitment, just as great postwar art had signature styles that point to but stand apart from the artist.  Jackie Saccoccio and Stephen Maine both have a shimmer that makes paint a mirror of more than themselves, while Keltie Ferris and McArthur Binion make a painting a site for their own body, without forgetting that paint and the genetic code have to stand on their own. And then Daniel Hesidence and Scott Ingram help tease the elements apart.

Jackie Saccoccio and Stephen Maine both have a shimmer that makes paint a mirror of more than themselves, while Keltie Ferris and McArthur Binion make a painting a site for their own body, without forgetting that paint and the genetic code have to stand on their own. And then Daniel Hesidence and Scott Ingram help tease the elements apart.

No more Pollocks

Jackie Saccoccio must be tired of having to distinguish herself from Jackson Pollock. You would be, too, if you made canvases up to nearly thirteen feet across, the drips as fresh as if they landed only yesterday. Seriously, though, anyone would be proud of the comparison, and Saccoccio invites it with a video of herself at work, putting paint through its paces. Life magazine, which made Pollock's gestures the expression of a formidably American painting, here we come. Yet she insists that her early ambitions lay in architecture, not in gesture, and that she feels closer to the voluptuous classicism of Renaissance Italy. As with a portrait by Titian, too, a woman is present.

Still, she and Stephen Maine both help to sustain the ideal of "all-over painting," and both are unsettling what goes into its making. Like Abstract Expressionist New York bringing downtown to the Museum of Modern Art, Saccoccio's two-gallery show straddles the Lower and Upper East Side. Like Pollock, too, she starts with a canvas on the floor. Her first marks, in red and other bright primaries, leave plenty of white space, like poured paint for Helen Frankenthaler or, in some series, Morris Louis. Then she raises the canvas perpendicular to the floor and gives it time, before adding more. She also moves with it, to impart gesture and direction.

She is not, though, showing off her forearms. She wears a cap with her head often out of view, as if to insist the painting matters more than the artist. She starts with stretched canvas and makes no big deal about assaulting it at its center. Rather, she stumbles about with it, much as its size requires, resting it now and again on another painting face up on the floor. Sometimes she places one face down on the other. Modestly enough, she is collaborating with herself.

Maine, too, relies on physical impressions to keep himself out of the picture. He takes one color as a kind of print bed. His spooky pinks and greens even look like silkscreens or inkjet prints. The mottled acrylic also approaches all-over painting more closely than Saccoccio's oils. They combine the intimacy of close detail with the deathlike chill of Andy Warhol. A handful of smaller works, like posters or, equally, easel paintings, bring out both sides of his craft.

Painting is back, to the point that it is not hard to pick favorites. Anything can seem derivative. It helps that both Saccoccio and Maine shy away from the big gesture and quotation of "zombie formalism." She has a point about Titian as well. Ovals in her work take on the look of storm centers or heads, sometimes in pairs, and mica adds greater luminosity. Uptown and downtown meet in strange ways.

Totemic heads can be derivative, too, via the Neo-Expressionism of Georg Baselitz—and Pollock deserves a little credit anyway. Talk about heads, and one should remember the increasing presences in his late black paintings. Talk about architecture, and one had better remember one of paint's great architects. Talk about modesty, and remember the radicalism of someone who allowed both to take their course. Still, Saccoccio and Maine deserve the comparison. After Pollock's descent into darkness, they manage both thought and pleasure.

Body double

Maybe the arbiters of Pop Art never fully embraced Tom Wesselman, who has escaped a museum retrospective, but then Wesselman never fully embraced Pop Art. Oh, collectors snapped him up, then as now, and his women still look like advertising spreads. Yet he often shied away from the label, just as he shied away from the irony. Forget the brute force of received imagery for Andy Warhol or an automobile for James Rosenquist. He really meant it: he was painting The Great American Nude.

Unless, that is, he never was. Maybe the real great American nude was the artist. For David Hammons, a body print evoked white fears, unrecognized black needs, and his own carefully nurtured invisibility. For Yves Klein, it meant his just as carefully managed stage presence, along with a dig at the heroics of Abstract Expressionism. This once, unlike for Jackson Pollock, an artist did not have to lean too far over an unstretched canvas to take a fall. And now the body is back without the macho overtones, thanks to a younger man and a woman.

In truth, Keltie Ferris seems at her shyest in body prints. She all but fades into the sheet of paper, abetted by bright red strokes marking the surface. Works on paper also fade easily into the background next to a dozen large canvases. These use jagged stacks of near squares, here and there amid airbrushing, to virtuoso effect. Again the entire image is elusive, but not for lack of showing off. To top it off, the same gallery will soon take up Wesselman.

Both pixels and an airbrush allude to impersonal media. Ferris could almost be presenting screen captures from burnt-out picture tubes, in fluorescent color. Coincidence or not, the Brooklyn artist completed the series in acrylic and oil while on a trip to la-la-land. Titles, too, combine the mythic proportions of postwar art with high-tech convention, often with characters from Greek myth in full caps joined by punctuation. Other titles, W(A(V)E)S and WoVeN, hint at a woman's traditional identification with passivity, the sea, and textiles, but this is painting all the same. Maybe abstraction is, after a break, too easy these days, but these earn their scale.

McArthur Binion lingers even more surreptitiously beneath his paintings, but also more insistently. He calls them his "personal DNA," redundancy duly noted, and he calls the show "Re:Mine." It, too, looks like a throwback to late Modernism, when painting meant something, but more to Minimalism, when it meant only itself. The grids consist of modest squares, each of parallel marks, the marks alternating between vertical and horizontal from square to square. They also have an insistent dark gray, as if to look as dreary as possible. More often than he might like, they succeed.

Still, they are well worth a second look. They incorporate fragmentary illegible handwriting, which adds the sole touch of color. Is this still another postwar mark of the artist, as confession? Not exactly, although they are his narrative and hearken back to an earlier point in time. A square's top border, in more impersonal lettering, repeats the state of Mississippi, where he was born a black male and an American nude, and these excerpt his birth certificate. Surface and gesture emerge from the cumulative impact of letters and a life.

Painting from above

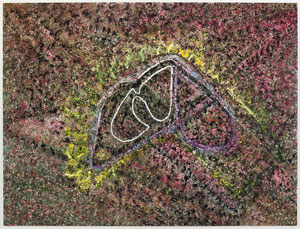

Conspiracy theorists should flock to see Daniel Hesidence. No, not the kind who imagine the art world as a handful of dealers, critics, collectors, and celebrity artists out to screw serious painters like them. Rather, anyone who believes in space aliens landing in the desert should find a testimonial to top-secret bases and airstrips. So should anyone who sees military maneuvers by the Obama administration as prelude to a federal takeover of Texas. Crazy? Maybe so, but Hesidence still takes time with paint to create a brute, scarred, and seriously colorful tribute to the medium and to landscape.

Actually, the first kind of conspiracy theorist could start here, too, for a reality check, much as in the Met Breuer's "Everything Is Connected.," Painting is alive and well, thank you, quite apart from open studios and DIY. Hesidence is one of many working on a large scale, as well as between realism and abstraction. He paints in series, with the shimmer of all-over painting, sometimes working outward from the center of the canvas in loops and swirls almost out of Cy Twombly. Yet some early series did find room for large, undernourished heads reminiscent of extraterrestrials. Now only the paint handling hints at representation.

Actually, the first kind of conspiracy theorist could start here, too, for a reality check, much as in the Met Breuer's "Everything Is Connected.," Painting is alive and well, thank you, quite apart from open studios and DIY. Hesidence is one of many working on a large scale, as well as between realism and abstraction. He paints in series, with the shimmer of all-over painting, sometimes working outward from the center of the canvas in loops and swirls almost out of Cy Twombly. Yet some early series did find room for large, undernourished heads reminiscent of extraterrestrials. Now only the paint handling hints at representation.

Starting over so often suggests an artist still finding himself, although the series share a focus on layering and color. Several critics felt that he had finally arrived in 2010, with untitled works in series as "Autumn Buffalo." Thinner and more fluorescent colors gave way to more surfaces both built up and worn down. The title, like the textures, invites comparisons to animal hides and cave paintings. Now the buffaloes are gone (and, as Carl Sandburg adds, "those who saw the buffaloes are gone"), but paint has thickened further, in small blots that press into one another's color, often right from the tube. Above them, the wide-open outlines of cave painting have settled into white.

The impasto, with its primaries and purples, takes on areas of bright reflections and dark earth. One really can imagine them as earthworks, with or without a practical purpose. The irregular white curves then take shapes of their own. Neither may represent desert enclaves, but both make sense as aerial views, in painting that invites close inspection but also detachment. The series title, "Summer's Gun," evokes weathering and weaponry, without quite explaining anything. Let it be our little secret.

Scott Ingram, too, nurtures both color and thickness, but as separate elements. Separation for him is a way of paring back. Ingram cares about the surface and edge of canvas as defining elements, although not in the manner of all-over painting. His rectangles of flat simple colors, in latex, and unpainted canvas function as the architecture of painting, much as in Minimalism. Canvas for him is a color, too. Then he reinforces that architecture in white.

While he is at it, he exceeds it. He builds up the white with marble dust and gesso, producing thickness but also disintegration. As if to separate out one last component from Hesidence, the glow, F+D (for Françoise and Daniel) Cartier use the back room for color photograms. Bras leave their flowing traces as whiteness, like masks. All these artists recombine much the same elements, without an academic retread of color-field painting. Not all abstraction has to rely on gesture and excess, and not all process art has to have a high-tech history.

Jackie Saccoccio ran at 11R through October 18, 2015, and at Van Doren Waxter (which hosts her video and where she has drawings coming up in late fall) through October 23, Stephen Maine at Hionas through October 4, Keltie Ferris at Mitchell-Innes & Nash through October 17, McArthur Binion at Galerie Lelong through October 17, Scott Ingram and F+D Cartier at Elizabeth Houston through December 6. Daniel Hesidence ran at Canada through January 6, 2016.