Officially Stylish

John Haberin New York City

Amy Sherald, John Dowell, and Jordan Casteel

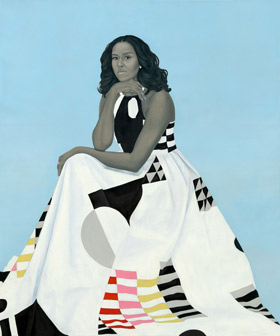

Amy Sherald became one of the most celebrated African American artists by painting one of the most celebrated African American women. It does credit to both women, her and Michelle Obama, as stylish and official.

Which woman did more to create an image for others to admire? If a portrait does the job well, it may never be easy to separate the artist from the sitter, the dancer from the dance. Nor is it the painter's only display of innocence, sophistication, and sheer pleasure in one and the same portrait. John Dowell, in turn, has his own monument to African American history, although he works anything but officially. He also has cottony skies, but he knows all too well who had to pick the cotton. He also knows where to place that history here in New York.

Like both artists, Jordan Casteel has one heck of an extended family. It includes fellow students from her time at Yale and her students at Rutgers today. It includes strangers on the subway or the streets. If she calls them all family, at the New Museum, it is not just tongue in cheek. It is also an aspiration, for she singles out those she most wishes to know. She also asks how much she can know—and how much they can know themselves.

The girl next door

People do not often swoon over official state portraits, least of all followers of art. It would be like swooning over someone else's yearbook photo—or a gold star from the world's primmest teacher. Yet here they were, portraits of Barak and Michelle Obama making the news. Visits to the National Portrait Gallery soared, and (as you can see from the link) I swooned a bit, too. The portraits arrived just as an awful lot of people were longing for leaders with intelligence and a conscience, rather than just a certain orange president. People longed, too, for voices with authority to speak for them.

Oh, and then there were the artists, Kehinde Wiley for the former president and Amy Sherald for his first lady. Wiley had appeared in galleries and museums before, often at that, for decorative, flattering, and frankly shallow portraits of African Americans off the street, all but exclusively young, aggressive, and male. He takes pride in his subjects, but with little hint that black lives matter and are at risk. Had he finally risen to the occasion, or had the occasion descended to him? Sherald, far less visible at the time, may offer a clue. Her latest portraits, much like Wiley's in the past, stick to moments of leisure and to friends.

Her mega-gallery also has a group show that thrusts human sexuality at once in your face and behind a veil, with artists including Paul McCarthy, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Mira Schor. Sherald does not. She makes desire so childlike that she adapted a famous photo of a kiss in Times Square at the end in World War II. Downstairs comes an older African American, Ed Clark—better known for his place in Abstract Expressionist New York and, quite possibly, the very first shaped canvas. Work since 2000 transforms even the purest of abstraction into glimpses of clouds and sky. For the gallery's fall 2019 opener and again for a Whitney retrospective in 2025, lavish brushwork looks back to the most gentle and glorious of summer afternoons.

Sherald feels the warmth, too, even as the real air grows cold. Four bathers, the women on the men's shoulders, enjoy the sand and a near cloudless sky. Who is to say which earns the painting its title, Precious Jewels by the Sea? A young black man sits high in a clear-blue sky, his butt on one girder and his back against another. Sherald took for inspiration a famous shot of workers at lunch, but this guy is neither dressed for work nor short of time. With just eight paintings, for once a hot artist ignores the pressure to churn things out, so you can relax, too.

For Sherald, attention to friends does not preclude a leap of imagination. As a self-portrait has it, When I Let Go of What I Am, I Become What I Might Be. Some pretty tart colors share space with that sky blue. She has room for reality all the same, from a handsome young man to the overweight "girl next door." Like Michelle Obama in her portrait, large central figures stand out against fields of color, almost like playing cards. They also share contrasting paint handling in figures, clothing, and backgrounds—to play degrees of realism against one another and to keep the surfaces alive.

Backgrounds are totally flat, but with wild swings in color from painting to painting. Flesh is well-shadowed, but not in the interest of anatomy or the fall of light. Faces are personalized, but not psychologically, and everything else pops to the surface, like a beach umbrella or a polka dot dress. Titles are poetic but erudite, like the recollection of Jane Austin's Pride in Prejudice in A Single Man in Possession of a Good Fortune. The title for the construction worker, If You Surrendered to the Air, You Could Ride It, speaks to him, but also to you. If they still feel too much like pages from the style section of a Sunday paper, consider them official portraits of the girl next door.

The spirit is rising

The spirit is rising. That may not be your first thought when you look back to slavery and its legacy, from Jim Crow to the brutal reality of racism today, and you may just as soon want to forget. John Dowell calls his show "Cotton: Symbol of the Forgotten" in order to remember. He might indeed be recovering cherished memories,  much as galleries and museums are recovering diversity in art. He introduces his photographs with the soft glory of cotton filling the air, as Spirit Rising. What does not kill him, it seems to say, will make him stronger—and what does kill him will take him to heaven.

much as galleries and museums are recovering diversity in art. He introduces his photographs with the soft glory of cotton filling the air, as Spirit Rising. What does not kill him, it seems to say, will make him stronger—and what does kill him will take him to heaven.

Sappy, like history as cotton candy? Kara Walker, five years after her sphinx for the Domino Sugar plant in Brooklyn, could fairly point out that slavery in the Americas also sustained the trade in sugar. Still, Dowell is not looking away, and he is also listening. If "Spirit Rising" sounds like a hymn, he accompanies the show with black voices singing, from a small speaker in the back corner. He also sets at least half his photos in and around churches. Cotton forms a tidy and inspiring bed leading right to the doorway or altar—even if the roof has caught fire.

Like RaMell Ross with his photograph of a fallen steeple, he recognizes the place of the church in sustaining African Americans as individuals and communities, and he has a short-lived New York community in mind as well. Seneca Village stood on Manhattan's west side from 1825 until it gave way to construction of Central Park. Some photos plop its small, frail church right down in a view across Central Park West. Dowell outlines it in quick, darting digital strokes of white and color, leaving the scene otherwise intact. The green expanse looks idyllic enough, much as it must have been that warm day for a male jogger and others. One hardly knows whom to blame for the forgotten.

Dowell's warm outlook and crisp focus do not preclude dark undercurrents, and never mind that plantations never extended to the city. A few more chilling photos, hung salon style, evoke a lynching—with a noose neatly framing Washington Square arch. More cotton rises in tall prints suspended from the ceiling as the show's centerpiece. Together, they take the shape of a shed, welcoming entry while barring an open passage. Their skies look ever so cottony and sunny, but people lived in such small quarters. And then they toiled or were swept away.

Still, sunshine wins out. What is not to like about entering the shed? Cotton also surrounds a shot of the monument to Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., just off Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard and in front of the Harlem building that bears his name. Powell, the first black member of Congress from New York, served for more than twenty-five years with a dedication to civil rights. Still, the striding figure amounts to the painfully heroic public sculpture that Kehinde Wiley parodies even as he milks it for all its worth. Dowell treats it with unalloyed respect.

Speaking of sugar coating, Powell also put his family on the public payroll, took public funds for personal use, and boasted of flings that today would make him a target for #MeToo. He swept away white machine politicians while creating a machine of his own. At heart, Dowell celebrates a sordid legacy, but at least he has the courage to look. The show's very first photograph converts the great American landscape into a panoramic carpet of cotton, in front of distant hills and red skies. You decide whether to call the moment sunrise or sunset. It also leaves a shallow foreground of deeply stained red earth.

Extended family

Questions about family and knowing have obvious relevance for a black woman, so often known on anything but her own terms. And Jordan Casteel calls her first series, from 2013 and 2014, "Visible Man," deftly overlooking her own concern for multiplicity. She riffs on Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, but then painting is all about the terms of the visible. Like Hayley Barker, she confronts the viewer with its visibility at that, with blue nudes a century after Henri Matisse. What did I do, you can hear her pleading, to be so black and blue? Their flesh plays off against the garish green and nasty grin of a child's toy, fiery red walls, a floral sofa, and the seeming eyes of a patterned robe that has fallen to the floor.

The contrasts are there for those willing to look, and not even friendship can reconcile them. These are striking works, although the work of an MFA student showing off. As an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in 2016, Casteel began to let her sitters and surroundings speak for themselves, while she in turn has contributed insights to a museum show of Jennifer Packer. She left color changes to the yellow glare of Harlem nights. If it came at the cost of flattery, her latest are more upbeat and complacent still. Still, they refuse to show off.

This is not the shallow glitz and strutting of Wiley and Mickalene Thomas. Casteel's figures spread their legs with a hint of the matriarchal or monumental, but just as much to feel halfway at ease. A boy leans awkwardly over his caretaker's knee in the painting that lends the show its name, Within Reach,  while the frame cuts off the adult's head. They might be too clumsy to pull off a proper Pietà. The flowers from a funeral have ended up in the trash. One can only hope that black lives matter.

while the frame cuts off the adult's head. They might be too clumsy to pull off a proper Pietà. The flowers from a funeral have ended up in the trash. One can only hope that black lives matter.

Not that people here are above taking pride. You gotta make them work for their money, reads a chalkboard, like I work for mine. Settings include a wine shop, a hair salon, a sidewalk dealer with CDs and a decent amp, and a popular Ethiopian restaurant. Students pose in their studios, with their work on the wall—not always great, but each with its own character. As the museum points out, her nights in Harlem brought a "renewed sense of place." But still, she asks, whose place?

Maybe we are all clichés, all the more so when we try to be ourselves. We have our favorite teddy bear or t-shirt, our brand-name sneakers, and the flags we fly—and they may be much the same as yours. Casteel's characters have entered a world of signs, and it can take a second glance to tell the characters and the signs apart. A shop owner has the dress shirts he sells, his own styling clothing, and the mannequin by his side. They belong to him, but he belongs to them as well. Casteel gives first names only, conferring at once intimacy and anonymity, enough to put pop-star black portraits to shame.

Their faces have the sharp highlights of Peter Saul on view a floor above. The mere forty works also combine a high gloss and degree of unfinish, in a kind of official portrait style since Alice Neel—although the curator, Massimiliano Gioni, would add a debt to African American portraits by Bob Thompson and Beauford Delaney as well. Still, the brushwork looks more fluid the more time you give it. Casteel has had an awful lot of attention for an artist who turned thirty-one the week of her opening, but she is still learning what she cannot know. It ain't about black and white, reads a t-shirt, cause we're human, and who knows what that might mean? Give her a little time to see.

Amy Sherald and Ed Clark ran at Hauser & Wirth through October 26, 2019, John Dowell at Laurence Miller through January 25, 2020, and Jordan Casteel at the New Museum through January 3, 2021. Sherald returned to New York at The Whitney Museum of American Art through August 10, 2025. A related review focuses on the Obama state portraits.