8.30.24 — Body Art

This could be the most difficult review that I shall ever write—not because the art is all that hard to explain, but because it is so painful to try. To describe a performance by Carlos Martiel is to relive the terror, disgust, and shame that he hopes to produce. I can only imagine the pain for him, at El Museo del Barrio.

Not that he is present in performance at a survey of twenty years of work apart from photographs, occasional video on small screens, and titles that are painful enough in themselves through September 1. It is still his “Cuerpo,” or body. Is it good or bad if he causes you to turn away?

Not that he is present in performance at a survey of twenty years of work apart from photographs, occasional video on small screens, and titles that are painful enough in themselves through September 1. It is still his “Cuerpo,” or body. Is it good or bad if he causes you to turn away?

Martiel is, somehow, still going in a line of performance art that includes Chris Burden, who dragged himself across broken glass, and Pope.L, who crawled the twenty-two miles of Broadway in New York. Not for nothing did ExitArt, the former nonprofit, call a group show “Endurance.” Still, their work can come across as a stunt, and Martiel is all the more vulnerable at thirty-five in remaining stock still. In that he is an heir to Yoko Ono, with Cut Piece, but the scissors that cut away her clothing never touch her for all their threat. He may be closer yet to Marina Abramovic, impassive and unmoving on a gallery shelf. Her work, though, is one long ego trip, while he harps on, let us say, serious matters.

Born in Havana, Martiel may come closest of all to another Cuban artist, Juan Francisco Elso—and I work this together with my earlier report on him as a longer review and my latest upload. A retrospective of Elso at the museum last year gave pride of place to Por América, a man in wood pierced by arrowheads many times over, like Saint Sebastian. And still the sculpture, modeled after José Martí, the Cuban revolutionary, wields a machete. His near namesake, too, fights back, but with his body on the line. Martiel has no time for epic heroes, the first Christian martyr, or fine art. He is a gay Cuban American in the real world, now.

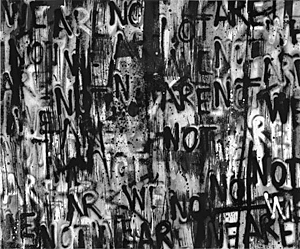

I have put off saying more as long as I could. This is his body and his show, although Por América could make a fine alternative title. In its very first work, not arrows but a flagpole pierces his skin, leaving the Stars and Stripes to drape from his chest. He has become a human flagpole, the very symbol of America, but an America that will never acknowledge him. Another flag hangs from above, with the red and blue turned to black and the white stained with blood. Let the blood be on your hands.

At the very least, it is all over his feet. They appear coarse and discolored in another performance. Blood is fresher still in another photo, where he holds a creature to his chest like a child or a pet. He might comforting it or taking comfort from it, but the seeming animal is only a loose collection of vital organs. It could make anyone who stares too long a vegetarian. What, though, does it say about gender, America, or him?

That can be a problem. Martiel can seem a one-note artist, and the note can ring all too clearly or hardly at all. He can also turn you away.That can be a strength, too, and critics must have brought the same complaints to Burden long ago. Martiel addresses Cuba’s repressive state honestly as well. He pins three of its medals directly to his chest—medals awarded to his father before him.

Still, it can fail. At his best, performance engages the viewer, daring one to turn away. He stands on a block in the Guggenheim’s rotunda, hands cuffed behind his back, like a slave at auction. He asks only for recognition, as a step toward freedom. In the show’s title work, he relies on others to save his life, with his neck in a noose as in a lynching waiting for him to fall. It is safe to say that enough people came through.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.