You Call This Anarchy?

John Haberin New York City

David Smith: Cubi and Spray Paintings

I came to "David Smith: Cubes and Anarchy" expecting a few more cubes and a lot more anarchy. One finds instead loops and planes, a great deal of empty space, and a dream of European Modernism.

From cubes to stick figures

The Whitney wants to make a case for Smith's Cubi, from 1963 and 1964, with just three of them. And it sees them as not just the culmination of one series after another late in life, but a return to his roots nearly thirty years before. Only it sees those roots not in an automobile plant of the 1920s or a childhood in the midwest. It skips past the ironworks of World War II—or the American art that burst on the scene soon after. Rather, it takes him back to his first years in New York and what he learned there. And what he learned, it says, was geometry.

He learned it well. Some artists grow overbearing in their last years, while some finally loosen up. Richard Serra manages both, wonderfully—although Serra's early years bear remembering. So did Smith, and it made his Cubi his lasting image. They have the scale of public sculpture, but the playfulness of stick figures. One seems to dance on one leg with its head about to fall, and it has its origin in his daughter running.

Two of Smith's cubes, connected like a dumbbell, fail to balance on their pedestal, and one rests on a pill-like shape that tempts one to wrestle it away. The fall of light on burnished steel looks improvised, too, as if Smith were sketching those curves freehand right before one's eyes. They play across the flatter sculpture of his last year, 1965, like helicopter blades about to spin off into the air. Still, the shapes set the work firmly in the 1960s, like a black cube from Tony Smith or a red cube from Isamu Noguchi. Noguchi's red cube occupies a bank plaza far from the Noguchi Museum in Queens, like many an Alexander Calder. They had found geometry, but had they lost their edge?

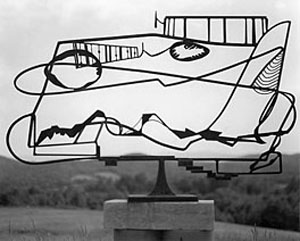

For years, David Smith stood for "drawing in space," and one can still see both the drawing and the space. Yet the phrase meant work from 1951—as a translation of Abstract Expressionism into sculpture. In time, he grew less linear, more massive, and relentlessly abstract. He seemed to have left behind the landscape and the lyricism. People grew to distrust grand old men and Minimalist geometry, and the Whitney is more than eager to look elsewhere. And that means looking to empty space and history.

The space starts right off the elevator. The museum uses its flexible architecture to clear out most of a floor, not unlike the video bowling alley for Cory Arcangel a couple of months before. It creates the breathtaking illusion of a sculpture park indoors, but not just for Cubi. Rather, it leads first to a flat red torus from 1962, with a green arc sticking out from its top. If the colors seem painterly, they stand in front of spray-painted silhouettes on paper. They could almost pass for photograms.

Nearby is the tabletop architecture of Noguchi or Alberto Giacometti—but enlarged and tilted to the point that the architecture looks certain to slide off the table. Something had changed since Abstract Expressionism, but not just geometry. John Chamberlain, too, was welding automobiles, but as the wreckage of Pop Art, an ambition that continues with Michelle Lopez today in beaten but luminous metal and folded wood. Smith found the steel in his Albany series in upstate foundries, as his own bit of appropriation. He was also employing assistants, like Andy Warhol in a different kind of "factory." For a moment, one can almost believe in anarchy.

Cubes, gods, and modernists

Then again, one could believe all the more in Smith's knowledge of art history. A title, Zig, puns on zigzag and ziggurat, like a comic strip for Mesopotamian women and deities. Which is it, then—Pop Art or history? The Whitney comes down firmly on the side of the gods. It allows representation to creep into abstraction, but as what Michael Brenson calls an "associative trigger" to ritual. And it tilts still further to the gods with The Hero and the Tanktotems, starting in the 1950s.

Along with open museum architecture, another kind of empty space is in time. The main hall also has smaller, more crowded steel of the 1930s. Smaller rooms in back hold other early sculpture along with modernist painting. Smith called a work from 1938 Suspended Cube, although the only cube in evidence is the space between masses. If one just forgets the 1950s, was he making cubes and totems all along? The first pile of actual cubes, from 1961, defines a Sentinel.

Forget, the show wants to say, the gaps and the inversions. Forget that a display of cubes has so few Cubi. Only do not forget Europe. Wall labels remind one of Jan Matulka, Smith's teacher at the Arts Student League, who exposed him to Russian Constructivism, Wassily Kandinsky, Kandinsky's late work, Piet Mondrian, and Julio Gonzales. Pablo Picasso manages to have experimented first with welded steel, as with everything else. Born in 1906 in Indiana, Smith did his first welding and riveting in Ohio, but he might have been working alongside them.

So, at least, says "Cubes and Anarchy"—and if that suggests a long and static career, it leaves a short and static display. Something happens when a sculpture park enters a museum. A room of photographs shows the sculpture as Smith saw it, in and outside his studio in the Adirondacks. They carry me from the spare museum floor to memories of Storm King, an actual Hudson River landscape, where I first saw him engaging the land. This show originated at LACMA, in a larger version, but make no mistake. The omissions are deliberate.

The sculptor has not lacked for rescue efforts. The Guggenheim had a David Smith retrospective as recently as 2006, and a show of his Personages followed in short order, while a show of his ex-wife, Dorothy Dehner, is coming up. Together, they sought a fuller picture and downplayed the Cubi. They stressed connections to representation and to early Modernism. The Whitney simply takes all that one step further. Yet in skipping the 1940s and 1950s, it largely skips the anarchy.

Nor is the Whitney alone in taking Smith from "drawing in space" to painting in space. These days, with almost every work an installation, artists move between two and three dimensions at the drop of a hat—or the click of a mouse. Lopez, for one, in her latest show included metal threads, hung vertically in a series, along a single wall, and saturated with paint. They seem somehow more permanent than her sculpture. For Grace Knowlton, for another, the transitions between media occupied a career. Yet that, too, suggests continuity in postwar American art.

Painting in space

Not to make a pun, Smith's paintings have never left much of an impression, and one can easily see why. As a sculptor he already had a larger canvas. He converted Surrealism's imagery into sculptural planes, before dispersing them into lines, curves, and blocks of polished steel. However, Smith had first wanted to be a painter, and a wartime shortage of materials got him thinking in two dimensions again, just in time to stimulate his breakthrough works. Besides, the former auto welder's "additive" approach has something more in common with painting than with carving. As a spray painter, he could have been working in an actual body shop, only sloppier.

Sometimes, as seen in 2008 at Gagosian, he brushes white paint over canvas saturated with sprays of red and blue. Sometimes the white takes on sharper edges, and I am guessing that he masked an area sprayed over it. Either way, the white mimics the familiar planes of his late sculpture. With the scale of easel paintings, at a time when Abstract Expressionism had made a larger canvas canonical, they even look like studies for sculpture. One could mistake them for works on paper, except that the spray texture and the weave of the canvas accentuate the spatter. It approaches the sparks of a welder's blowtorch.

Sometimes, as seen in 2008 at Gagosian, he brushes white paint over canvas saturated with sprays of red and blue. Sometimes the white takes on sharper edges, and I am guessing that he masked an area sprayed over it. Either way, the white mimics the familiar planes of his late sculpture. With the scale of easel paintings, at a time when Abstract Expressionism had made a larger canvas canonical, they even look like studies for sculpture. One could mistake them for works on paper, except that the spray texture and the weave of the canvas accentuate the spatter. It approaches the sparks of a welder's blowtorch.

The white, together with the appearance of a stencil, leaves a ghostly geometry against the acrid colors. The sculpture looms as a kind of missing presence. At the same time, the paintings help rescue his sculpture from its grand reputation. Smith executed his Spray series in roughly five years, starting in 1958, at a time when he was moving from such open, linear works as Hudson River Landscape to the monumental later series. Yet as a spray painter he anticipates graffiti art. The white marks move across the canvas like an unknown alphabet.

If Smith's paintings annotate his career, like an extended footnote, Knowlton, now in her seventies, has painted all her life. She, too, likes additive methods, and her trademark spheres of metal and ceramic came about as art accumulated material. She treats another two-dimensional medium, too, as a kind of compendium of creative processes. Knowlton's photographs, also in 2008, what might pass for sculptural maquettes, the wisps of perhaps cardboard or paper spiraling back on themselves. Their shadows have the texture of brushwork even untouched, but Knowlton also works over some in pastel. To round out the story, a desktop sculpture in brown steel picks up the same shapes.

One can picture her drawing from nature, turning it into sculpture, photographing that, accentuating its three dimensions in paint, and at last literally closing the circle in steel. As if in confirmation, she includes a couple of drawings of reclining nudes from the mid-1970s, with some of the same loose curves. They also come closest to the paintings of hers that I know best—lean black tracery on white, like winter landscapes or stained glass. However, Knowlton actually photographed found objects, in plain old wicker, and several larger digital prints isolate the dowels in colorful but peeling chairs. They look back to an old-fashioned definition of abstraction, as abstracted from life. More to the point, they root painting and sculpture in the shadows and materials of an artist's life.

Can the Whitney do as well for Smith? Postmodernism is still wresting with Modernism, and contemporary art is still wrestling with both. They have claimed Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning both for formalism and for chaos. Two versions of Smith, a decade apart, appeared this year in MoMA's "Abstract Expressionist New York." Another of his photographs takes abstract delight in black shipboard smokestacks. Perhaps they just came over from Europe—but there is no going back.

"David Smith: Cubes and Anarchy" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 8, 2012. Michelle Lopez ran at Simon Preston through October 30, 2011. Smith's spray paintings ran at Gagosian through February 23, 2008, and Grace Knowlton at Lesley Heller through February 9. Related reviews look at "David Smith: A Centennial" in 2006 and Smith's white sculpture.