12.27.24 — Mapping the Universe

So many Eastern religions have embraced mandalas as connections to something beyond everyday pleasures and everyday cares. So many everywhere have marveled at their decorative richness.

Followers of Carl Jung have weighed in as well, because what Jungian can resist universal truths? So take a deep breath before entering the Lehman wing at the Met. “Mandalas” asks to appreciate them for what they are—not just catch phrases and aids to meditation, but literal guides to the spiritual universe. As the show’s subtitle has it, it is “Mapping the Buddhist art of Tibet,” through January 12.

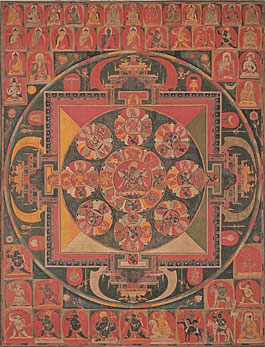

You may need a map, a believer all the more so. This intricate universe reads outside-in, with concentric rows, columns, and circles of symbols like stamps or playing cards for the many steps in Vajrayana Buddhist practice. Over time, the rituals became more and more distinct, corresponding to distinct Tibetan sects. And the show also displays accessories to practice, most over a hundred years old. They are the practices of a warrior, with swords and shields. They are the practices of a celebrant, with masks, drums, and a trumpet so long that it could easily outstrip the trumpeter.

Oh, and what a universe it is. Buddhism has had its appeal to Westerners like Herman Hesse for its simplicity, especially in the spirit of the 1960s. It has seemed to tell a very human story, of the man who walked away from worldly temptations to become Siddhartha (or he who has achieved his goal) and the Buddha. Here you will encounter the five Buddhas, countless gods, their retinue, and their consorts. By that point, you may need an intercessor, and this form of Buddhism has plenty. They include goddesses, but also bodhisattvas, those who have achieved enlightenment but not yet become gods.

If they sound foreign to the jealous gods of the West, just wait until you meet them. They can be protectors, a source of hope as your karma determines who you will become in the next life. After a couple of centuries of Himalayan Buddhism, they begin to offer hope, too, to escape the endless cycle of reincarnation. Still, the most merciful gods are the ones with deadly weapons in the battle for enlightenment. But then the most austere in reputation are the sexiest. By all means, then, grab a map.

The Met has only a room for mandalas, off to the side. Rather, the show’s three main stages introduce the gods, the intercessors, and the rituals. The curator, Kurt Behrendt, sees them as getting you comfortable with the cast of characters before you reach the show’s true subject. In effect, they are maps to the maps. They all surround a central atrium with its own payoff—murals and carpets by a contemporary artist, Tenzing Rigdol. They present calm seas and rising or sinking suns in gloriously bright colors. They offer space to breathe and a place to rest.

Traditional paintings and sculpture are packed with detail. Ten heads rise up from one deity’s shoulders while samples of a thousand arms fan out. Patterns lend color—a predominant red, but alternating with blue, yellow, and green. A sun-struck yellow may serve as skin tone, but so may blue, sometimes faded to black. Pigment applied directly or mixed with glue, as distemper, adds intensity. The works may date back to the eleventh century, but they peak around 1350.

No question they take adjustments from ignorant Westerners like me. The cells of color flatten surfaces, but gods have a turn at the waist almost like Renaissance contrapposto, which announced a new humanism and a new approach to mass, motion, and depth. That turn at the waist can approach a dance as well, sometimes a wild one. Surviving practices include human dancers with loose robes and demonic, animal, or downright comic heads. All of these are about as far as can be from Chinese art or a show last year of not so early Buddhism. You may wish for more, like, say, mandalas traced in sand, but you could never have imagined a distinct north Asian universe.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.