Mapping the Universe

John Haberin New York City

Tong Yang-Tze and Lee Bul

Mandalas and Monstrous Beauty

I do not go to the Great Hall of the Met at year's end to look for art. As a New Yorker in holiday season, I am too busy human dodging traffic and counting the seconds in line. It moves fast, but that hardly describes a decent work of art.

Stillness, though, comes easily to Tong Yang-Tze with the ancient practice of calligraphy on a suitably grand scale. She covers the walls to either side of the entrance. For once, even a hardened critic or shopper has to look up. Can even she keep a tradition alive in the crowd, no more than Lee Bul on the museum façade? Further within,the Met has traditions in all their creation and perseverance, Tibetan mandalas and, later, Chinoiserie.

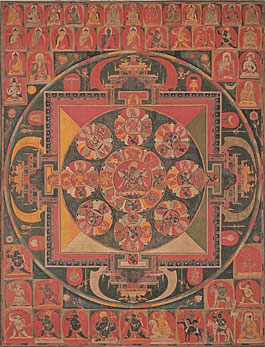

So many Eastern religions have embraced mandalas as connections to something beyond everyday pleasures and everyday cares. So many everywhere have marveled at their decorative richness. Followers of Carl Jung have weighed in as well,  because what Jungian can resist universal truths? So take a deep breath before entering. "Mandalas" asks to appreciate them for what they are—not just catch phrases and aids to meditation, but literal guides to the spiritual universe. As the show's subtitle has it, it is "Mapping the Buddhist art of Tibet."

because what Jungian can resist universal truths? So take a deep breath before entering. "Mandalas" asks to appreciate them for what they are—not just catch phrases and aids to meditation, but literal guides to the spiritual universe. As the show's subtitle has it, it is "Mapping the Buddhist art of Tibet."

The most fragile and beautiful of art forms has become a monster. Make that "Monstrous Beauty," in what the Met calls "a feminist revision of Chinoiserie," but women themselves keep getting in the way. Lee Bul is among them, just as she prepares to leave her niche on the Met's façade, and the whole heads for the Lehman wing, just months after mandalas. But does it rescue women's art for women or write them off as less than spiritual? Are they Asian art or European? What century is this anyway? They may have unleashed a monster.

A show of perfection

It is not easy to find a moment of peace in a museum atrium—or even a work of art. At the Morgan Library, since its 2007 expansion, you are probably too busy eating to care about either one. Since MoMA's 2019 expansion, the block-long lobby is little than a waste of space, unless you buy into a tall projection as AI art. The Met's first Great Hall commission, by Kent Monkman, went for murals of Native American history, as busy the coat check and a lot more pretentious. Jacolby Satterwhite preferred video, but visitors may have mistaken it for an ad, if they spotted it at all. Tong Yang-Tze does better by engaging, her title announces, in Dialogue.

The Chinese artist really is in dialogue—between art and poetry, images and words, East and West, herself and history, the work's surface and New York's most imposing space. A translation speaks of the "other," but otherness for her is a necessary condition of humanity or art. As a child, she fled the mainland for Taiwan, at the cost of a divided family. She has designed her adopted homeland's passport seal. Her text at the Met might challenge anyone to put it to use. One must divide it into columns before reading from top to bottom and right to left.

That allows ink to spread across the paper, like "all-over painting." (Your favorite Abstract Expressionist here.) At left, trailing dabs have a presence of their own at top, all but detached from their place in letters and words. They play against curves that flaunt their creation in a single stroke—or the impression of one. The work at right is simpler still, although still close to drip painting. It suits the terse allusiveness of Chinese poetry and art.

A rehanging of the Met's Chinese art pairs painting and calligraphy, while Japanese art from a private collection claims these and poetry as the "three perfections." Sure enough, the Great Hall makes a show of perfection. As one text has it, "Stones from other mountains can refine our jade." As an online translation of the other runs (with no mention of the "other"), "Go where it is right, stop when one must." And so she does, leaving plenty of white space. The look of improvisation plays off against aphorisms some three thousand years old.

The Met will never permit a free lobby gallery like the ones at MoMA and the Whitney. It does, though, continue with its façade commissions. Lee Bul uses its sculptural niches for Long Tall Halo. It adopts the metallic shine of a commission by Carol Bove in 2021 and the statuary of Wangechi Mutu the year before. It may not have the sanctity of a halo or the pop appeal of "Long Tail Sally," the song, but Korean artist tries for both.

She is at heart a show-off masquerading as a crowd pleaser. She speaks of hoping to disgust the viewer, but you know better. She had her hall of mirrors, with a suspicious resemblance to infinity rooms for Yayoi Kusama, and the Fifth Avenue expanse of Museum Mile will do just fine for infinity. Bul uses the pedestal within a niche for a vertical component, like a poor excuse for a mythic hero. Her construction of small spirals then spills forward and out, twice ending in a point. Her subjects cannot get it up or keep it in.

Escaping the cycle

You may need a map to the Met's mandalas, a believer all the more so. This intricate universe reads outside-in, with concentric rows, columns, and circles of symbols like stamps or playing cards for the many steps in Vajrayana Buddhist practice. Over time, the rituals became more and more distinct, corresponding to distinct Tibetan sects. And the show also displays accessories to practice, most over a hundred years old. They are the practices of a warrior, with swords and shields. They are the practices of a celebrant, with masks, drums, and a trumpet so long that it could outstrip the trumpeter.

Oh, and what a universe it is. Buddhism has had its appeal to Westerners like Herman Hesse for its simplicity, especially in the spirit of the 1960s. It has seemed to tell a very human story, of the man who walked away from worldly temptations to become Siddhartha (or he who has achieved his goal) and the Buddha. Here you will encounter the five Buddhas, countless gods, their retinue, and their consorts. By that point, you may need an intercessor, and this form of Buddhism has plenty. They include goddesses, but also bodhisattvas, those who have achieved enlightenment but not yet become gods.

Oh, and what a universe it is. Buddhism has had its appeal to Westerners like Herman Hesse for its simplicity, especially in the spirit of the 1960s. It has seemed to tell a very human story, of the man who walked away from worldly temptations to become Siddhartha (or he who has achieved his goal) and the Buddha. Here you will encounter the five Buddhas, countless gods, their retinue, and their consorts. By that point, you may need an intercessor, and this form of Buddhism has plenty. They include goddesses, but also bodhisattvas, those who have achieved enlightenment but not yet become gods.

If they sound foreign to the jealous gods of the West, just wait until you meet them. They can be protectors, a source of hope as your karma determines who you will become in the next life. After a couple of centuries of Himalayan Buddhism, they begin to offer hope, too, to escape the endless cycle of reincarnation. Still, the most merciful gods are the ones with deadly weapons in the battle for enlightenment. But then the most austere in reputation are the sexiest. By all means, then, grab a map.

The Met has only a room for mandalas, off to the side. Rather, the show's three main stages introduce the gods, the intercessors, and the rituals. The curator, Kurt Behrendt, sees them as getting you comfortable with the cast of characters before you reach the show's true subject. In effect, they are maps to the maps. They all surround a central atrium with its own payoff—murals and carpets by a contemporary artist, Tenzing Rigdol. They present calm seas and rising or sinking suns in gloriously bright colors. They offer space to breathe and a place to rest.

Traditional paintings and sculpture are packed with detail. Ten heads rise up from one deity's shoulders while samples of a thousand arms fan out. Patterns lend color—a predominant red, but alternating with blue, yellow, and green. A sun-struck yellow may serve as skin tone, but so may blue, sometimes faded to black. Pigment applied directly or mixed with glue, as distemper, adds intensity. The works may date back to the eleventh century, but they peak around 1350.

No question they take adjustments from ignorant Westerners like me. The cells of color flatten surfaces, but gods have a turn at the waist almost like Renaissance contrapposto, which announced a new humanism and a new approach to mass, motion, and depth. That turn at the waist can approach a dance as well, sometimes a wild one. Surviving practices include human dancers with loose robes and demonic, animal, or downright comic heads. All of these are about as far as can be from Chinese art or a show last year of not so early Buddhism. You may wish for more, like, say, mandalas traced in sand, but you could never have imagined a distinct north Asian universe.

Monstrous Women

To be sure, even fine porcelain can get out of hand, and the Rococo made that a virtue. Along with flouncy clothes and depicted gardens, it became the very art of excess in the hands of Jean Antoine Watteau, Jean Honoré Fragonard, and François Boucher—who took it from Rococo to revolution. How fitting that the Met's exhibition comes just as the Frick Collection reopens to the public. To be sure, too, critics have looked to its sources in trade with the East, if not outright seizure. They have asked as well how the decorative arts served as a label for the display of wealth. It allowed its dismissal as less as less than fine art, better suited to China and women.

Monstrous, perhaps, but not half as monstrous as enormous porcelain filling the Lehman wing to overflow. Yeesookyung takes its two-story atrium for gilded fragments in dark colors. The surrounding halls include a handful of other contemporary Asian and Asian American artists, set amid a larger show of a more gilded age. There, too, context is everything, and paintings reinforce the role of decorative arts in defining a portrait sitter's character for James McNeill Whistler or the transience of existence for Dutch still life. His interior could almost be a knock-off of "Whistler's mother," but with darker shadows. Either way, the Chinoiserie she values lies everywhere in the background.

Is it truly monstrous, though, and are the monsters women? The Met has a fondness for embedding contemporaries amid past art, to show history's relevance, as with Tibetan mandalas last year in the very same space. It sells, but if anything it upstages the past. Looking for a proper history of Chinoiserie, Asian or European, and what set it apart? The work scoots casually across centuries of fans, mirrors, tapestries and tea sets, in no particular order, with carvings and castings almost entirely by men, as one might expect. A collage from 1929 by Mariana Brandt throws Anna Mae Wong, the Hollywood actress, but much has nothing at all to do with Asia.

Why, too, these contemporaries? They include ridiculously ornate porcelain towers by Heidi Lau and Lee Bul, with limbs like writhing snakes. Others, though, appear solely for their take on Asian women. Lau calls hers Anchored the Path of Unknowing, but the curator, Iris Moon, seems awfully knowing. Women's art, she argues, can only be monstrous because so are stereotypes of women, when they are not simply effeminate. They are queens, mothers, starlets, shoppers, cyborgs, and little more.

One might dismiss women as shoppers, but cyborgs? (Mothers have their own issues.) The show itself points to other roles, as gossips over the tea table or as temptresses from the ocean's deep. That goes back to the very birth of European literature in Homer, and here they are again on video for Jen Liu, in The Land at the Bottom of the Sea. Candice Lin has her salon, while Jennifer Ling Datchuk plays on narcissism with mirrors, one sprouting hair, and Patty Chang leans into herself on video as well. Arlene Shechet might have entered for her own ceramics, but then they would not be monsters.

They do, though, make a good case for monsters in contemporary art. Chang also spoons melons out of her left breast, and she may have suffered the most at that. Her bare white table could pass for a surgical bed awaiting its next patient or, given its holes, an instrument of torture awaiting straps. It may take a moment to recognize it as a work of art. There is a role for Chinoiserie in defining beauty, but the torture is real. Blame it on your mother.

Tong Yang-Tze ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through April 8, 2025, Lee Bul through May 27, "Mandalas" through January 12, and "Monstrous Beauty" through August 17.