12.13.24 — The Eagle Takes Flight

“God forbid we should ever be twenty years without such a rebellion.” Thomas Jefferson was speaking of Shays’s Rebellion, an uprising seeking debt relief and back wages from the Revolutionary War, but the Met is well ahead of his schedule in reconceiving history.

Not twelve years after reopening its American wing, the museum celebrates the wing’s centennial with a new look for American art.

Not twelve years after reopening its American wing, the museum celebrates the wing’s centennial with a new look for American art.

In truth, it is less than a revolution. The painting galleries have nominal themes, but with due respect for movements, artists, and their times. Other changes have been in the works for years. One still enters through a bank facade, although the Met has long since added its own money maker, a popular café. One can hardly help entering onto rooms for Native American art, once sorely neglected, along with other rooms for “founding narratives” (aka period rooms). Allow me, then, to offer once more my personal guided tour from January 2012, starting here.

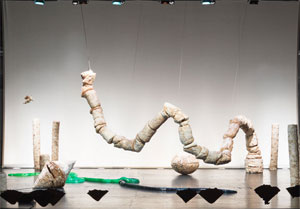

A gilded eagle had an unlikely flight. William Rush carved it in 1809 and 1810, for a Lutheran church in Philadelphia, where it supported a sounding board behind the pulpit with its iron tongue. By mid-century it had come to rest in Independence Hall, not far from Rush’s own statue of Washington. Now, still suspended by a chain and still atop its gilded sphere, it presides over the first room in the Met’s new American wing, which soars.

Of course, its meaning has changed—from an attribute of Saint John to the American eagle to the spirit of American art. Rush understood national symbols all along, though, and so does the Met. It centers the wing on a single floor for painting and sculpture, from the colonial era to the Ashcan school. And it centers that floor on its hoariest display of patriotism, Emanuel Leutze’s life-size Washington Crossing the Delaware. It does so with a knowing wink at its audience, too, like that of Robert Colescott to embody the painting in blackface. The press would not have insisted so often on Leutze as icon rather than art without the museum’s prompting.

Of course, too, the painting is storytelling, and the renovation is telling stories as well. Lots of them, in fact, and they overlap. By bringing painting together on one floor, the Met sets out American history as a series of unfolding themes. The same characters often reappear in new roles, as artists or as subjects. By moving the Ashcan painters here as well, it also says that the evolution of American themes did not end abruptly with Modernism. The museum gets to boast of its collection as at once authoritative and open-ended, and it makes for a terrific reintroduction to American art.

The American wing took its present shape less than thirty years ago, with the museum’s first distinct galleries for painting and sculpture. The Met could simply have shut the place down and started over, as it did for Islam. Instead, change has come gradually over ten years, with a reopening in stages since 2007. The new painting galleries merely complete the job. The basic architecture has not changed either, although the firm of Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo has found another three thousand or so square feet of display space. Yet this time small changes matter big time.

From changing images of Washington to changing images of the wilderness and the city, Met does not just present a history. It makes painting look good, by making paintings look at each other. It places sculpture in almost every room, from portrait busts to duck decoys. It shows the American eagle still in flight, not quite ready to land, with the textbook triumph of American painting another fifty years away. With luck, the wing’s stories will keep changing. Will Washington Crossing the Delaware be their centerpiece forever?

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.