Culture Vulture

John Haberin New York City

The American Century: Art and Culture

"One sees a modernist painting as a picture first." Thirty-five years ago now, an influential critic meant that as a compliment. These days one is more likely to hear the buzz before one sees any art at all.

This summer, with "The American Century: Art and Culture," the Whitney Museum has people talking as much as looking. As the title alone suggests, here and in Part II coming up the museum is staging a cultural event.

A colorful title, like a cover for Time magazine, meets a subtitle right out of postmodern academia. An awful lot of claims come packed in that awkward combination. Is there any room left for American art or the twentieth century? Is there room, in fact, for an insight into those big words art and culture? (You may also wish to compare this with a review of a much later survey of the permanent collection, "Full House" in 2006.)

All that jazz

Of course, the Whitney means every word. It has filled the museum's five floors with a century-long retrospective of American Modernism and American culture. And that just takes one up to 1950: the second half will follow in the fall. Will America still own the century at its end? Well, stay tuned.

Starting with "Genteel America," each decade comes with its label. The museum charts the rise and fall and rise again of American optimism—from "The City" and "The Jazz Age" to "Depression America," "Wartime America," and "The Emerging Avant-Garde," with more tales of anxiety, myth, and recovery along the way. Paintings come set out by themes, interrupted by old movies, book covers, consumer products, and popular song. Pillars bear miniature TVs for dance crazes, although by no means to upstage one of the film alcoves, with Fred Astaire at his most effortless. One can hardly believe he is dancing.

Women and black artists enter the pageant as never before, both in dedicated blocks and as individuals. I was truly glad to see three successive panels from The Migration Series by Jacob Lawrence. Archibald Motley turns out to have the intense life and flat colors of contemporary art. One could easily quibble with many choices, and a traditionalist might hit on these, but mostly the show sticks safely to greatest hits—and then some.

Clever pairings of photographs give the diversity special urgency. Laurie Gilpin is up there next to Ansel Adams, Lisette Model alongside Weegee. One can hardly miss America's agonizing history either with Gordon Parks and his "A Harlem Family." He photographs black children hanging onto a white doll, their hold—on the doll, on themselves—so treacherous and caring.

Photography indeed gets full rooms all over the joint, quite a retrospective of its own. At times an artist turns up in an unfamiliar medium. I had not known Ben Shahn as a photographer or Marsden Hartley as a blunt portraitist, but I will not forget them now. I have wanted ever since the Jackson Pollock retrospective to see Thomas Hart Benton as a muralist, and small mock-up dioramas do the job well.

The Whitney's show was in place before recent management changes, but I have to credit the details—and so the new regime—for the exhibition's finest hours. The movable walls lend the jazz age some dizzying spaces. They also leave several rooms more comfortingly like home than I have seen before at the Whitney. Wall labels with outrageous photo blow-ups may hector, like the impressive but endlessly didactic Web site for the show, a long way from the Web's very promise of an artist-driven community and exhibition space. Still, they do not surround each and every last work.

Genteel America?

A show this ambitious packs excitement, before one shows up. And I felt the thrill for at least a short time inside, too. I felt it in the very first room. One starts at the top, on the museum's fifth floor.

Frank Benson's elegant society woman functions almost as static first, something to help one adjust coming off the elevator. Her dress and equally glittering figure amount to one more bit of Japonnaiserie in a fashionable interior, like anything from T. W. Dewing a generation before. Lost in a stupor, without even the flair of John Singer Sargent's high society, she can hardly manage to put down a card in her game of solitaire.

And then I saw Robert Henri's portrait of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Next to Benson and his peers, I could hardly miss it. Whitney lies on her couch, a traditional pose for the overt sexuality that American art still took as a provocation. It still sounds impressive coming from a museum's upper-class founder. One can almost forget Thomas Eakins and his daring portraits not all that long before this show even begins.

Traditionally, of course, a woman on her couch exists for men. Whitney commissioned this one, naturally, for herself. If I had any doubts that this woman was in control, her confidence would straighten me out. So would the strident colors. Compared to Benson's decorative lady, she sticks out from the background like a sore thumb, one she earned the hard way after a good knock-out punch. Henri's framing ferns parallel Benson's forms, but they serve the sitter rather than the other way around.

Like any regular museum visitor, I knew the painting by heart. In this show it came alive for me, though, and so did Henri's commitment to modern art. I better not forget Whitney's own commitment, too, when she opened up her studio.

And yet over five floors and five decades I never once had an excitement like that again. The society that Whitney flaunted and scorned takes over, just as it does when the exhibition calls that room with her portrait "Genteel America." Thanks to its theme of America's cultural history, the Whitney sees combinations such as Benson and Henri as elegant variations on a theme—as with so many recent shows there, from Joseph Stella to Arthur Dove, a provincial one.

America first

Think about it: "An American Century." It boasts of an art that boasts of America, where someone like Charles Burchfield in Burchfield's early work or Lyonel Feininger at heart fears it. One knows it from the start: this show takes equal pride in post-Impressionist art for the elite, the self-conscious grandeur of Mark Rothko and painstaking progress, and Grant Wood for his wary celebration of family values. It admires art that takes for its subject a nation's drive into history. That includes the urban experience and the post-urban marketplace.

"A century." A show like this has to take the long view. Did critics call Abstract Expressionism "the triumph of American painting" after decades of provincialism—or in ignorance of postwar European abstraction? This show will trace America's greatness to the bare dawn of an era. It enjoys defining historical eras, for that matter. Let others worry about an artist's lonely struggle for understanding.

Oh, yes, "Art and Culture." That, too, has a familiar ring. I started by quoting Clement Greenberg, the great defender of abstraction, and here the Whitney takes the title of Greenberg's best-known book. Theft, how very postmodern—and for the Whitney the title literally boasts of an American spectacle. Forget Modernism's elites, for this country drew its strength from wave after wave of immigrants. But do not forget, diversity fans: the illusion of a nation comes first. Hoist three flags, if only from Jasper Johns.

"Art and Culture" may echo Greenberg, but he dismissed the topic in his first few pages. For Greenberg, art had to redeem culture from kitsch, so the less said about the masses the better. In this show, cultural trends pack all the significance of political events, much less fine art. The medium is the message, and I do not mean the oil medium. The 1960s here means Woodstock as much as Vietnam, the 1940s the flag raising at Iwo Jima as much as a world war.

"An American Century: Art and Culture." Above all, that lengthy title boasts of more than America, the country that found a champion in a dealer, Edith Halpert. The show brags about itself. Like the Museum of Modern Art in its own survey of mid-century choices or the Guggenheim shying up to the year 1900, this museum wants to set the textbook on early modern art. It parades one great, familiar work after another, just as in the good old days of the canon. It gives no obvious quarter to contemporary doctrine. Even photography or "low art" shuffles off to its own corner rather than hangs side by side with oil. It never packs the wallop that Walker Evans and his "American photographs," picture postcards, and decaying billboards once had in challenging fine art and genteel America.

To sum it up, a peculiarly postmodern chauvinism underlies the show's claims. This museum announces its place in this century—and the next one, too. Only a properly postmodern museum would set content and culture first, above artistic personalities. This American century fills with dance halls and skyscrapers, not Dada and the Armory Show. Amid all the spectacle, I actually mistook the Johns flags in the lobby for a reproduction.

The avant-garde as style

The show's patriotic lecture may be right or wrong, and it often feels right. But it pays a fat price for where it goes wrong. For starters, think of the price a woman would pay for losing Whitney's and Henri's avant-garde gesture, no matter how many blacks and women are on display.

In fact, the whole idea of an avant-garde art goes out the window. Breakthroughs remain, but assimilated to cultural artifacts. Oils come so rarely that I even came to crave them.

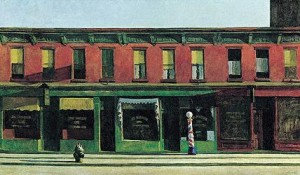

Artists get several works together only when they fit clearly into the theme. John Steuart Curry does, say; Edward Hopper does not. Early Sunday Morning sits apart from his other work, side by side with Isaac Sawyer's unemployment office. Forget about Hopper's ability to define and isolate individuals. Forget about his inexorable development or piercing light. His painting must snatch what pessimism it can from another, lesser artist's theme of abandonment.

High-falutin' modernists like Hopper or Berenice Abbott come off the worst, their works scattered to the winds. (Oh, how much she means to another millennial survey, at the Museum of Modern Art.) It is as if the Whitney has no clue what to do with them. Certainly it has no tolerance for protests against flag waving. Woody Guthrie makes it only on account of "This Land Is Your Land."

For Europe the avant-garde was a cause. For America it was at times a shock, as with Oscar Bluemner, but also long a style, and this show is high on style. Duchamp's old urinal acknowledges European Modernism, but the shock of its introduction here slips by with hardly a mention. Someone who mattered to the Armory Show as much as Albert Pinkham Ryder never appears.

Naturally the exhibition makes the least sense at its end. Once the ideological drama of a depression and a war peter out, not much is left. One has to settle for babble about an "idealized world" and the "presence of uncertainty of the human condition." The tiresome themes of "action painting" and "chromatic abstraction" make for an incredibly dull selection of postwar art. Only Arshile Gorky comes off halfway well. But then his self-portrait with his mother detaches easily from the history of abstraction.

Culture, documentation, and style

The reduction of the avant-garde to a style says a lot about what goes wrong. The show hoped to energize art through its place in culture, but like a historian uncovering homely Renaissance sculpture for private worship or a Renaissance scholar's study, it ends up estheticizing high and low culture alike. I cannot tell you which of Pollock's drips turned up, but I do recall that Reginald Marsh could draw well.

The show's only other pole is documentation. After the wall labels' leaden history, even the superb array of photography comes off as journalism. The exhibition catalog does much the same. Postage-stamp paintings and pocket history become sidebars to a nation's central, cultural heritage.

Sometimes it takes manipulating chronology to make the narrative flow properly. Peter Blum stands next to Philip Evergood, artists a decade or more apart. Gorky and his mother also appear ten years out of place. Oh, and that Jasper Johns flag in the lobby dates from 1958, around the time of the first encaustics by Johns in gray. So much for this first half century when a show's logo is at stake.

The show's themes do no better in the end than Greenberg. Like him, they leave no room to examine the interplay of art and culture. They accept diversity—of race, gender, or style—but not outright conflict. A multicultural canon is okay, but not rejection of a single canon in favor of multiplicity.

With five floors, no question but so much is going on here. The show's themes may have trouble facing up to the richness of American art and American personalities, but they make their case anyhow. I wanted to cry out that the "city" of which the show so often boasts is New York, a landscape I know well. It has also been the site of multiple heritages, strange pleasures, anger, poverty, and betrayal. Here it is no more than an icon for industrial or jazz-age America.

I made it through five floors in less than three hours my first time, a sure sign that some challenge was missing. But no question about it: fifty years of American art makes an impact, and it did on me. Am I looking forward to the next fifty years or dreading them? Maybe a little of both. But then, I feel that way about the coming century, too.

Part I of The American Century runs at The Whitney Museum of American Art through August 22, 1999. Part II will open September 26 and run through February 2, 2000.