12.20.24 — Vanishing Act

Every self-portrait is a boast—a double boast. Yes, says the artist, I am a worthy subject, and yes I can pull it off with my art.

With “What It Becomes” at the Whitney, make that a triple boast, through January 12. Yes, its adds, I am worth hiding as well. There was more to me than you saw all along, and it is up to you, the viewer, to find it. As David Hammons has it, Close Your Eyes and See.  .

.

Self-portraiture’s dual or triple nature goes back to its origins, in the Renaissance. An artist like Albrecht Dürer could boast not just of his skill, but of a new-found status relative to his patron as well. For Dürer in silverpoint at age thirteen, he had not yet even earned a patron. With “Hidden Faces,” covered portraits of the Renaissance at the Met last spring, every portrait was also a mask. Its sitter, after all, had an image to convey, too. By the end of 1960s, though, when the Whitney begins, the mask itself became a place to hide.

“What It Becomes” does not speak of masking. It calls art a way “to reveal the unseen” and to “make the familiar unrecognizable.” In other words, it is about self-creation. The curator, Scout Hutchinson, also speaks of art’s material presence, even in a space largely dedicated to works on paper from the museum’s collection, just outside the education department. It is about “inscription, erasure, and tactility.” It is a vanishing act all the same.

Presence is as presence does, starting with David Hammons. His body prints put himself into the act, but not to show his face. A famously reclusive artist, he reveals nothing, least of all his skill in drawing. They might as well be tire treads. He confronts, too, a black man’s invisibility to white eyes or, worse, violent removal. Body prints by Yves Klein in blue, not in the show, seem an empty boast by comparison.

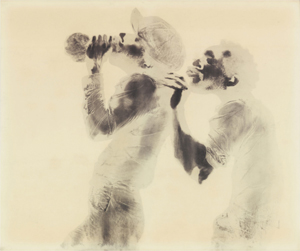

The small show could be a catalog of strategies for vanishing. Some play the part of others, like Darrel Ellis in black wash, posing after a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe. Wendy Red Star leaves herself out entirely in favor of a leading Native American around 1880. The same red outlines in ink-jet prints frame her text and a hatchet in his hands, both as weapons. Toyin Ojih Odutola gives black skin to “famous whites.” Jim Hodges works with his own saliva, but the results look more like pond scum than a portrait.

Naotaka Hiro promises to Map His Body, with pretty enough colors but not much else. Others appear explicitly, but masked. Rick Bartow takes on the teeth and smile of a wild animal, in pastel and pencil. Maren Hassinger takes pains to apply her mask, like a woman applying makeup, but as blackface. I cannot say for sure whether her video celebrates, defies, or condescends to gender and race, but it resonates. Blythe Bohnen acquires her mask simply by time-exposure, so that the blur of her features serves as a beard.

Catherine Opie hides behind nothing more than her back and its blood-red incisions. And Ana Mendieta, never one to hide, brings one last strategy for vanishing. She sets an effigy on fire, leaving her very body image in flames. Self-portraits have become all but a ritual these days, as an affirmation of personal and cultural identity. These eleven artists look back to a time after Modernism when such things came with irony and pain. For all their flaws, they could still mean more than what it all became.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.