A Final Resting Place

John Haberin New York City

Robert Mapplethorpe and Mapplethorpe Today

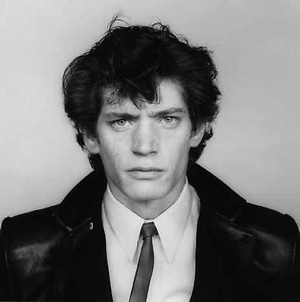

In his last self-portrait, Robert Mapplethorpe finally took a seat. It is just one of many searing images at the Guggenheim in "Implicit Tensions," drawn entirely from its collection.

It highlights how much he thrived on portrait photography and, most movingly, self-portraits. It boasts of the museum's holdings, thanks to a gift of two hundred works from the artist's estate way back in 1993. Because photographs are almost always multiple, one can recognize many of these from elsewhere, and the Guggenheim has no trouble representing Mapplethorpe as a whole. It shows his transition from assemblage, thanks to the gift of a camera, which he turned immediately on himself. The "implicit tensions" extend to questions of formalism and desire well beyond portraiture. But what does that say about Mapplethorpe in the present?

If he were alive today, would he seem any less provocative or exemplary? Would anyone trust yet another white male to speak for black Americans, female empowerment, or his own generation lost to AIDS? Would he be a model for LGBTQ art even now or a mere period piece? Two weeks after its retrospective, the Guggenheim stakes a claim for "Mapplethorpe Today." Its younger artists and photographers pick up where he left off, but not without a serious challenge to his authority. He argues right back from beyond the grave.

A death's head

No doubt he had to sit, for in 1988 he was dying of AIDS, and his face seems to belong to an older man. Mapplethorpe had his final resting place the next year, at age forty-two. Yet he granted himself not just a chair but a throne, much like Rembrandt in a late self-portrait in the Frick Collection. One cannot make it out in the darkness, but one can see it in his posture, his command, and his unblinking stare. Where Rembrandt used a painter's stick for his scepter, Mapplethorpe holds a death's head. He, too, was the monarch of all that he surveyed, and all that he surveyed was his mortality and his art.

People do not often sit for Mapplethorpe. He was a studio photographer, not a street photographer, but he could set up his studio anywhere, and he kept people in motion. He has Patti Smith, a favorite subject and a lover, ducking in and out of the shower, as Still Moving. (Oh, those implicit tensions.) She might be a dancer, with the shower curtain as her seven veils. He shows her again in slow motion, playing against her shadow on the wall.

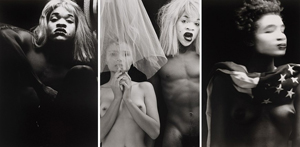

He shows her naked, drawing up her knees with her hands on the radiator, to see whether she can hold her pose. When a black model draws up his knees, the nude may hold still, for now. But photographs show him in turn from all four sides, as if they were themselves in motion. Other men kiss, strut, or struggle, in the kingdom of S&M. Splayed out in his very first Polaroids, Mapplethorpe, too, seems in bondage, but his only partner is the camera or himself. When he gets off the floor, he is still struggling, but his photographs could be long songs all the same.

When people do get to sit, like Brice Marden, they look restless. David Hockney and Henry Geldzahler, the painter and curator, take to the roof, while Philip Glass and Robert Wilson, the composer and director, can barely hold the same frame. And when they do hold still, beware. One man in bondage hangs upside down by his ankles, like a crucified Saint Peter—and the photographer was raised as a Roman Catholic in Queens. Another stands beside his seated lover, like mobsters demanding homage, but in leather and in chains. Mapplethorpe himself poses as a terrorist or revolutionary, in front of a Star of David and with a black automatic weapon in his arms.

Yet he transforms action into stillness. In his still lifes, every flower stands in isolation apart from a seedling or its shadow. It might be in readiness for opiates or a funeral. They also bring out Mapplethorpe's nurturing of contrasts in black and white. He uses shadows, tables, and molding to lock them into place—like a skull the year of that last self-portrait. He takes the pose with knees drawn up from elements of classical architecture.

The polarities of black and white correspond to those of desire, much as for Tiona Nekkia McClodden today. He loved black men and black models, and he relished the reflection off shaved heads and black skin. He also poses a black nude with a man in white makeup, covering the entirety of his visible flesh. Lisa Lyon, the bodybuilder, raises a white fist, but from behind a black veil. Mapplethorpe turned to photography in 1970 with a Polaroid camera, which can make any flesh look made up—and not just that of Candy Darling, the transsexual and Warhol superstar. Andy Warhol sought the same effect in his own Polaroid portraits.

Explicit tensions

Mapplethorpe was the master of explicit tensions, too—between black and white, clean lines and texturing, art and impulse, beauty and desire, the forbidden and permitted, sex and death. Be careful, though: one cannot disentangle the opposites or reduce the tensions. Wall text speaks often of formalism, but also of S&M, in his words, as "sex and magic." The Guggenheim has tried before to rescue him from perversity in favor of the "classical tradition," in 2005. Yet his photographs depend on their power to disturb even you or me, not because that is their true character, but because it is inseparable from their formal temptations.

Can they still deliver? It is not easy, not when art can absorb every rebellion. Well after conservatives have tried to shut down his shows and deny arts funding, he has become a classic. So has Diane Arbus, whose madmen and madwomen have come to reassure gallery-goers of their sanity and sensitivity. Yet Mapplethorpe still shocks. His art still has its harsh contrasts, while his subject matter still looks like anything but art.

The curators, Lauren Hinkson and Susan Thompson with Levi Prombaum, proceed by a loose mix of theme and chronology. It makes sense for the museum's tower gallery, which does not itself unfold in a straight line, and it makes sense for Mapplethorpe. They have one hefty assemblage, a barrel topped with rubber and a crucifix—and then a collage in which found clippings anticipate the photographs. The first Polaroids still have heavy frames. With his turn in 1972 to a bulky Hasselblad (another gift), he could at last nurture his virtuosity and dedicate himself to the medium. It made him a studio artist once and for all.

It also brought out his skill in portraiture, with figures from the arts. They include Cindy Sherman, who curated his work for a classy Chelsea gallery in 2003, as "Eye to Eye." Others appeared in the gallery's "Fifty Americans" in 2007. Even then, Mapplethorpe defies expectations. He refuses to make a portrait an emblem for anyone's public image or art. Alice Neel screams in pain, so very far from the casual air and creature comforts of her paintings, while Warhol gets a halo of off-the-shelf artificial light.

Louise Bourgeois, for all her art of female sexuality, showed up with a sculpture, her sculpture, of a phallus. And that brings out another strength in the portraits, a willingness to collaborate and to try things. In his self-portraits, Mapplethorpe keeps trying things out—and that means trying on potential selves. He poses in female makeup, in a boa, in a dress shirt, in leather, with a smile, with a scowl, and with a cigarette. Like a young David Wojnarowicz masked as Arthur Rimbaud, he plays the hipster and the rebel. It must have come as a shock to learn that he could not play the part to the bitter end.

In that last self-portrait, the rebel has become the damned. And the equation of sex and death for Mapplethorpe, for all its psychological truth, has become all too real. So has the fraying of a community, a decade after his photograph of a frayed American flag. Still, he adopts death as his scepter and his realm, and he looks it squarely in the face. Where Wojnarowicz, another victim of AIDS, goes out screaming, he refuses self-justification or anger. He cannot settle for an easy answer, because he can feel the tensions in his flesh and bones.

Objectifying Mapplethorpe

"Mapplethorpe Today" might have you expecting artful pairings with everyone under the sun, to show the extent of his influence and a curator's ingenuity—at the cost of diminishing everyone. With distinct sections for him and just six others instead, the museum dares one to draw connections. You might expect, too, gay white males like Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz. Mapplethorpe's latest challengers are anything but. Outside on the ramp, artists get entire floors for their selections from the museum's collection, as "Artistic License."  And here, too, the six eyes bring a reverent but critical examination.

And here, too, the six eyes bring a reverent but critical examination.

Five of six are black, including Zanele Muholi from South Africa and Rotimi Fani-Kayode from Zambia via the Black Arts Movement in London—a movement that also featured Lubaina Himid in painting. The sixth, Catherine Opie, could be tearing into Mapplethorpe's artful use of S&M, much as she lacerates a corpulent female body. Fani-Kayodes shifts the focus from New York's gay community under fire to displacement and exile, while Lyle Ashton Harris and Glenn Ligon both quote Frantz Fanon on colonialism. Paul Mpagi Sepuya hides his traces behind mirrors, just where Mapplethorpe refuses to turn away. Ligon, known for text art in painting and neon, is not even a photographer.

Ligon does, though, provide a starting point in the black male. Margin of the Black Book from 1993 adds text to the nearly one hundred pages of Mapplethorpe's Black Book from seven years before, quoting everyone from critical theorists to a bartender. The quotes also make clear what Ligon and the other five challengers have in common—the question of who gets to speak for whom. Fani-Kayode, who died of AIDS in 1989, is no longer speaking, but the rest sure are. Still in his thirties, Sepuya has come in no time to represent LGBTQ art, in the 2019 Whitney Biennial and elsewhere. Opie in her self-portraits and "American Cities" already did.

Still, they cannot set themselves above their desires, no more than Mapplethorpe. The echoes are everywhere. His portrait of Lisa Lyons echoes in Opie's raw flesh or her high-school football player acting tough. The individuality of his African Americans collides with their sculptural beauty, much for Muholi's and Fani-Kayode's Africans. Muholi, too, knows the sheen of sweat on black skin, the artifice of staged portraits, and the casual intimacy of lovers and friends. When Grace Jones, the singer, poses for Mapplethorpe in skin-tight clothing designed by Keith Haring, she could be a surface for street art or Muholi's Dark Lioness.

Only Fani-Kayode made a point of his influence, "as a weapon." Still, a wall-sized collage by Harris makes Mapplethorpe another estranged father along with Jeffrey Dahmer, the serial killer. Harris also cross-dresses like him and lends women a ghostly blur. They look like Candy Darling in Mapplethorpe's Polaroids. If Sepuya makes a point of the studio as a "site" and the darkroom as a "mirror," the older artist took the box camera of studio photography with him wherever he went. A couple for Muholi look back to Mapplethorpe's interracial embrace—his heads cut off, much like the faces that Sepuya refuses to reveal.

Did Mapplethorpe "objectify" his subjects at the cost of their humanity? For Susan Sontag, any photographer does—including, no doubt, everyone in the Guggenheim's loaded selection. Still, in Ligon's margins, he denies using the camera as a subject for the male gaze. "Sex without a camera," he replies, "is far more interesting." Does Ken Moody in the margin think to himself, "I look like a freak"? In his last self-portrait before dying, Mapplethorpe understood that he did, too.

Robert Mapplethorpe ran at The Guggenheim R. Guggenheim Museum in two parts, through July 10, 2019, and January 5, 2020. Andy Warhol Polaroids ran at Paul Kasmin through March 2, 2019. Related reviews linked in the text cover previous Mapplethorpe exhibitions and scandals.