2.17.25 — MoMA Without Modern Art

Imagine the Museum of Modern Art without The Starry Night. Now imagine what it would have become without its founding director, Alfred H. Barr.

Not easy, is it? At one point, a turning point, as the museum approached its landmark opening in 1929, the two were at odds, and just try to guess who won. The outcome brought the museum that much closer to a canon for modern art, thanks in no small part to Lillie P. Bliss. Now MoMA gives her and her collection their due, to put its finger on what was at stake, through March 29.

Not easy, is it? At one point, a turning point, as the museum approached its landmark opening in 1929, the two were at odds, and just try to guess who won. The outcome brought the museum that much closer to a canon for modern art, thanks in no small part to Lillie P. Bliss. Now MoMA gives her and her collection their due, to put its finger on what was at stake, through March 29.

Few exhibitions rewrite history, although more than a few try. With just forty works from the Lillie P. Bliss collection, the Modern rewrites its own history. Generations, me included, have learned how a young professor at Wellesley College gave modern art a defining history, one that lasted the rest of the century—and, to its credit, one that MoMA itself has worked hard for a while now to revise. Barr created a canon that started in Paris and found its fulfillment in New York, on the cutting edge of the present every step of the way. That is why he planned the new museum’s opening show on Fifth Avenue to stick to then contemporary American art. It took just three women to shoot it down.

As MoMA tells it, Bliss, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, and Mary Quinn Sullivan were its true founders—with the indulgence at most of John D. Rockefeller himself. The three got the idea and contributed its core. Sick and tired of the crowds in front of The Starry Night, which is not even modern? Now you can see it much as it once stood in a private collection. Bliss also allowed her work to be sold to fund new acquisitions, a museum no-no today, but that helped pay for such stalwarts as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, by Pablo Picasso, as well. (That work still hangs in the main galleries.)

The founders saw a growing interest in the art that had shocked New York in the 1913 Armory Show, where Bliss first publicly exhibited her collection. She showed again at the Met, but she was not a precocious or instinctive collector. She met Arthur B. Davies, a painter of nudes and landscapes, and John Quinn, among the first collectors of modern art. Both had her looking back to the last century, with the Symbolism of Odilon Redon. She collected Georges Seurat as well—like the precision of Seurat drawings in Conté crayon in black. She found a new freedom, though, well into her fifties, with the death of her mother, who had needed no end of care.

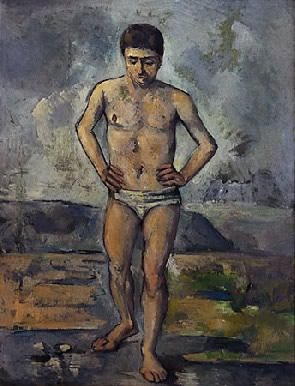

And that freedom had her looking to the present—and to a future museum for modern art. I, for one, could easily leave The Starry Night to Vincent van Gogh on loan a year back to the Met. I could not imagine the Museum of Modern Art, though, without Paul Cézanne. No one else so embodies a vision of modern art as rigorous but constantly probing, even as the artist all but despairs of finding completion. And that vision was Barr’s. Still, Bliss collected work spanning Cézanne’s career, including Uncle Antoine, Pines and Rocks, Still Life with Apples, and the large Bather.

I still marvel at how his uncle plays the artist himself, how firm the bather seems, and yet how evanescent he is as well. I still marvel at how the weave of a forest both invites and defers the sun. I still marvel, too, at how the pattern on a cloth seems to tumble out onto a table with the already unstable apples. Bliss had caught onto something, and Barr must have been a welcome discovery as well. Still, she and her co-founders had to object when his planned opening show excluded Europe. Maybe her relative conservatism was at play, too, in starting with Post-Impressionism, but not altogether. Still, the women did not have to threaten a veto to change Barr’s mind, for he knew all along just how much lay at stake.

The show will never be “major,” and work will return to galleries for the museum’s collection when it is done. It includes letters, a telegram, newspapers, and the guest book from the museum’s opening for those who want to rewrite history for themselves. To the end, though, Bliss was still helping the museum keep up with its times. She bought Paul Gauguin woodcuts and a grandly flat portrait by Amedeo Modigliani. She bought Picasso’s Woman in White and the view out a window by Henri Matisse with an empty violin case and sunlight’s silent music. She died in 1931, never to see MoMA in its own building just blocks away from its first home, the one she knew.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.