7.8.24 — A Woman’s Rise and Fall

Käthe Kollwitz started her career with death and ended with love. It could just as easily have gone the other way around.

Her first print series, from the 1890s, follows a worker’s revolt from its beginnings in Need and Death. This is A Weaver’s Revolt in Silesia, industrial country, where workers knew need and death well. A march that should be a triumph of solidarity and action looks more like a forced march, the workers hunched forward in weariness. And then comes simply End,  with bodies on cots and the living barely set off from the darkness, pondering what has happened and what is to come. Her art comes down to the rise and fall of dignity and democracy, at MoMA through July 20. She knows, though, where she stands and how much she has loved—and I bring this together with a recent earlier report on the politics of German Expressionism and a forthcoming one on Paula Modersohn-Becker as a longer review and my latest upload.

with bodies on cots and the living barely set off from the darkness, pondering what has happened and what is to come. Her art comes down to the rise and fall of dignity and democracy, at MoMA through July 20. She knows, though, where she stands and how much she has loved—and I bring this together with a recent earlier report on the politics of German Expressionism and a forthcoming one on Paula Modersohn-Becker as a longer review and my latest upload.

Each series by Kollwitz has the same arc of death and love. Peasants’ War from 1902 to 1908 looks to the sixteenth century for models, and it finds one in a woman sharpening a scythe. It, too, ends in violent suppression. A third series, just after World War I, testifies to the costs of war. Titles speak of Mothers, The People, and Survivors, but not as heroes. Rows of women and children look formidable in their grief.

Kollwitz felt the arc of rise and fall personally. Born in 1867 in East Prussia (parts of today’s Russia and Poland), she moved to Berlin in her twenties with her husband, a physician who saw to the poor. She learned grief from his patients. Quickly acclaimed, she would have won a gold medal at the Berlin Art Exhibition had not the Kaiser himself stepped in. An award to a leftist and a woman would have gone too far. Still, war’s end made Germany a republic—and made her a professor at the Prussian Academy, its first woman ever.

Yet the arc had not finished with her, not by any means. She lost her younger son in the Great War, and the elder almost died from diphtheria. She lost her teaching position and freedom to exhibit to the Nazi rise to power. She died just weeks before their fall. It seems only right that MoMA hangs A Weaver’s Revolt from left to right, so that one encounters first its end. Still, she had found her purpose as an artist in insisting on the purposiveness of art.

Kollwitz took to paper because of that purpose. Prints to her meant multiples, to reach the people, like poster art to this day. It also allowed her to rework her art with a record of every stage. She combines woodcuts, etching, lithography, and drypoint, enhanced with sandpaper—and then overlays prints with whatever comes to hand. Her drawings could pass for series, too, as she begins again and again. If there is a progression from start to finished product, it eludes me.

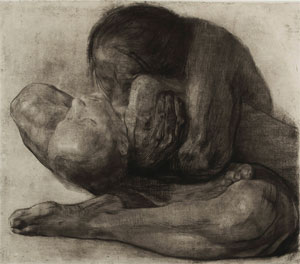

She never lets go of a theme either, like revolts and state violence. That includes her most titanic drawings, of a mother with dead child. That woman holding a scythe has almost the exact same pose, but with a sharp object in place of a child. By the show’s end, she has taken up sculpture, and the pose has become first lovers after Auguste Rodin and, at last, a mother protecting her child from death as the ultimate act of love. It involves the same confusion of hands and limbs. It looks back to a Renaissance Pietà and the contortions of Mannerism—but then she was an academic, and other deaths recall a Dead Christ in older art.

The curators, Starr Figura with Maggie Hire, open with self-portraits as an extended prologue, but they, too, recur often. Kollwitz betrays neither fear nor certainty, her cross-hatching touched by washes and highlights, like the shine on her forehead. By the show’s end, she has documented aging with unflinching realism. She belongs to the first wave of German Expressionism, but without the gilded flattening of Gustav Klimt or the swollen, exaggerated hands of Oskar Kokoschka. She responds to World War I much like Max Beckmann, but not to satirize Berlin high society. She was never, for all her greatness, a revolutionary in her art, but she still has her arc and her archetypes of the people.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.