Expressing Oneself

John Haberin New York City

The Self-Portrait: Egon Schiele to Max Beckmann

George Grosz: Eclipse of the Sun

Was there ever so self-conscious an art as German and Austrian Expressionism? "The Self-Portrait, from Schiele to Beckmann," at Neue Galerie, shows painters blisteringly aware of the medium and themselves. It also contrasts sharply with a consciousness of others, in the Neue Sachlichkeit and George Grosz.

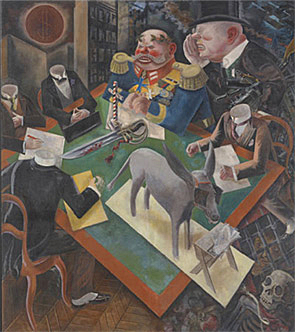

Sometimes it helps to put a face on history. You may know Paul von Hindenburg for his role in the Nazi seizure of power. As president of the Weimar Republic, he named Hitler chancellor in 1933, when the party had only a minority in the Reichstag. He became the very image of cowardice and conservatism—putting a legal face on the death of democracy, out of belief that he could control it.  Grosz might have called it Germany's Eclipse of the Sun. He might, that is, had he not used that very title in 1926, for a painting that already put a terrifying face on von Hindenburg and his country's fate.

Grosz might have called it Germany's Eclipse of the Sun. He might, that is, had he not used that very title in 1926, for a painting that already put a terrifying face on von Hindenburg and his country's fate.

It is a darkly comic face as well. As field marshal, von Hindenburg had led Germany to defeat in World War I, and Grosz shows him in full military regalia—and with the laurel wreath of honor or peace on his bald head. Stout and ridiculous, he stares right past a candy crucifix and literally empty suits, while a robber baron whispers in his ear. His ruddy flesh above a walrus mustache could stand for the blood on his hands, like the bloody sword on the table before him, or a clown's makeup. If that reminds you of a certain overweight orange president, the painting could almost predict the threats to American democracy as well. On loan from the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, Long Island, it also anchors thirty paintings and works on paper from the Weimar Republic.

Consciousness and corruption

The artists in "The Self-Portrait"and the Neue Galerie were conscious of themselves as painters—and as painters in a society corrupt to its core. They were conscious, too, of their attraction to that society in all its high style, not so far after all from a painter as fashionable as Gustav Klimt. Looking out from a canvas, they are also conscious of you. They put you on the spot even before you enter the exhibition, within the glorious 1914 mansion on New York's Upper East Side. As you ascend the spiral stairs, you encounter full-length photographs of Egon Schiele and Max Beckmann. They could be responding to one another as well.

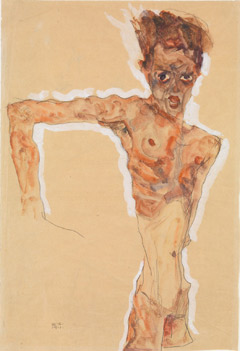

Schiele glances at his reflection in a full-length mirror, always his own best subject and never quite satisfied with himself. Beckmann looks straight out, ever the observer of others. Schiele can hardly trouble to pose, with one hand in his pocket and his mop of hair—only that, too, is a pose. Beckmann plays the bourgeois and the dandy, even when he can barely make ends meet. In a self-portrait, he is rarely without a cigarette. In his self-portraits, Schiele cannot often manage to dress.

Beckmann looks the older of the two because he was. Born six years before Schiele, in 1884, he survived the Nazis and Nazi-looted art in exile in New York, and he used painting as a bitter commentary on his era. He thought of each thick line, harsh contrast, or sloppy gesture as a measured response. Schiele barely made it to the art of World War I, and the collision of pride and anxiety arose completely from within. He turned out one self-portrait after another before his death at age twenty-eight. What looks thoughtful was a radical invention, and what looks impulsive probably was.

Not that either artist invented the genre. As long ago as the Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer drew himself in a demanding medium, silverpoint, at age thirteen. In a crowded painting of mass martyrdom, he lurks at its very center. While the exhibition has only a copy, it leaves no doubt that German Expressionism sets artists within a larger catastrophe, only they make no effort to hide. A later German, Anton Raphael Mengs, turns up as well, because even an academic painter had to put himself on the spot. Rembrandt gets space for seven etchings on loan from the Morgan Library, because one can hardly speak of the self-portrait without him.

And that is just for background, to give Schiele his due. He appears in a watercolor at age sixteen, slightly older and far more sullen than Dürer. He appears in Conversation with a woman or maybe a ménage à trois, but they do not appear to be talking. In another painting, they share an unmade bed, their bodies in parallel. Yet they lie head to foot, with her butt in the air and her face nowhere to be seen. Already, the body is already contested ground.

In drawings, Schiele focuses repeatedly on what a past show called his "obsession," meaning himself. He twists an arm behind his back further than it could possibly go. He appears marked by splotches, as from the plague, and as Saint Sebastian, the early Christian martyr. Even when he dons a clean shirt and tie, he leaves the better part in shadow. He is trying on poses, like Rembrandt—or like Cindy Sherman before her time. In a sheet of three heads, all three are versions of him.

Self-aware or self-conceit

Beckmann, in contrast, is a study in detachment. He found fame and fortune in the Weimar Republic, but one would never know it from a devastating family portrait. Six people and a seemingly life-size statuette share a cramped room in impossible perspective. They ignore one another as best they can, even face to face, while a dog takes over the piano, so that no one else can rest or play. Beckmann eyes himself, but a woman preening reserves the sole mirror. Candles rise to either side of a bottle on the kitchen table, because their flames may die and the alcohol may soon be drained.

Nearly twenty years later, in exile, he holds a horn to one ear, like a hearing aid, as if better to attend to the horrors on every side—or to prepare to bring it to his lips to sound the alarm. A hunting horn recalls German folk culture, before the Nazis claimed just that for themselves. It also marks Beckmann as the aristocrat amid the rabble and the hunter amid the haunted. He sports a lavish robe, in public and in private, with no care to distinguish the two. He is self-consciously an artist, even without an easel or mirror at hand. Between Schiele and him, the show lays out the expressionist self-portrait.

Its seventy works by more than thirty artists run well beyond the Neue Galerie's collection, with many an unfamiliar name. It includes the frontispiece for a portfolio of self-portraits, to further its claim. (Michael Fingestein does show himself at an easel, with a mirror.) It has a wall for drawings, with Paul Klee head in hand, as yet another act of reflection. Photographs push expressionism toward the experimental. Herbert Bayer plays a life-size mannequin, which he promptly dismembers—leaving a dislocated shoulder and a poor excuse for a woman's breast.

Its seventy works by more than thirty artists run well beyond the Neue Galerie's collection, with many an unfamiliar name. It includes the frontispiece for a portfolio of self-portraits, to further its claim. (Michael Fingestein does show himself at an easel, with a mirror.) It has a wall for drawings, with Paul Klee head in hand, as yet another act of reflection. Photographs push expressionism toward the experimental. Herbert Bayer plays a life-size mannequin, which he promptly dismembers—leaving a dislocated shoulder and a poor excuse for a woman's breast.

Most, though, is painting. Portraiture merges with street scenes, as with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and with a chilling social realism. Felix Nussbaum shows himself in 1940 in an internment camp and again in 1943, holding out an ID card as a Jew, as a dark wall and darker cloud close in. He died the next year. Oskar Kokoschka picks up the themes of disease and martyrdom. He turns his back on a female model, and the ghostly figure on his canvas looks more like him.

Grethe Jürgens, Paula Modersohn-Becker, and Käthe Kollwitz recover the body for women. Modersohn-Becker depicts herself as plain, even in the nude—and even as she identifies with the decorative richness of the wallpaper behind her. Kollwitz immerses herself in shadow, after trying out the charcoal with a few smudges and doodles. Lyonel Feininger adds Cubist fragmentation. With all four, the self-conscious is consciousness of art.

When the show speaks of the self-portrait, it speaks of the genre as not just an extension of the artist, but as a thing to itself. Lovis Corinth includes a painted self-portrait, but his painted face is downcast, even as the artist to its side is not—and he, too, was soon to die. Otto Dix and Rudolf Wacher sit at their easels, and they could be painting you. Their faces convey a harsh scrutiny. They all depict the artist, but they have others in mind as well. For them, the self-portrait helps rescue the self-aware from self-conceit.

Not the orange president

von Hindenburg was already close to eighty in 1926, and democracy was already besieged. A dollar bill, too, rests on the table, because capitalism for George Grosz supported the republic and found a willing tool. So does a donkey or maybe a wooden toy donkey, which feeds at a trough of paper. The empty suits hold more their pens to more blank paper, as all the good that government and business leaders could produce. The table itself is covered with green as if for billiards, while a skull rests beneath it on the floor. Set diagonally at the painting's center, the table nearly crushes a flat and unstable space.

Stairs climb up to the one side of the table, echoes of its diamond shape in floor tile to the other. The pattern also merges smoothly with a chain-link fence, with a boy looking desperately from behind. If his generation represents Germany's future, things do not look good. An eclipse of the sun does appear, at top left, its red filling the sky above burning buildings. And Grosz had death on his mind, starting with the sixteen million military and civilian deaths between 1914 and 1918. The painting, the show argues, may stand for art of he Weimar Republic, but it belongs firmly with the art of World War I.

It was also part of a new energy in art and a new realism. While the museum's overlapping show of portraits straddles German and Austrian Expressionism, this one links Grosz to the Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. He confronts the world even as he shares its turmoil. That new objectivity also ties to the ideal of a "New Woman," free to bare her flesh without becoming a martyr or a whore.  And the show has seven portraits by Otto Dix, five of them of women, along with a woman in a bow-tie by Rudolf Schlichter. Old and young, they seem more wary than welcoming or proud.

And the show has seven portraits by Otto Dix, five of them of women, along with a woman in a bow-tie by Rudolf Schlichter. Old and young, they seem more wary than welcoming or proud.

Grosz himself has a sharp-eyed portrait—of a man with a glass eye. Lean and well-dressed, he nurses a cigarette while intent on a newspaper. In this haunted world, a glass eye may see as clearly as any. Other work, from the Neue Galerie collection, rounds out an acid portrait of Germany in the 1920s. More fat cats dominate a factory landscape by Georg Scholz, while pillars of smoke pollute the air. Max Beckmann complements Grosz's interior with another compressed space of sharp colors and severed, grasping hands.

Beckmann also contributes six of the eleven lithographs in his Hell. Their thick but spare outlines could pass for charcoal, but their vision is acid. From a hungry family at a bare table to street-corner ideologues and a crowded street, Germany's hell is other people. Was this, though, really hell? It must have seemed that way, right down to Grosz's city in flames. Yet the worst was yet to come.

Weimar was still a republic, and the Great Depression that shattered it could easily have shattered America as well. The dollar was not yet almighty, and in fact American money was helping to pay off the reparations foisted on Germany by Europe. Criminal violence did at least as much as legal complicity to install a dictatorship, and Grosz like Beckmann fled to the United States. He returned home only the year of his death, in 1959, at age sixty-five. Like Beckmann, too, one may remember him less for his realism than his disdain. Yet his sun still burns even in eclipse.

"The Self-Portrait" ran at the Neue Galerie through June 24, 2019, "Eclipse of the Sun" through September 2.