In Praise of Intellectual Beauty

John Haberin New York City

Description is revelation.

— Wallace Stevens

Why Art Takes Words

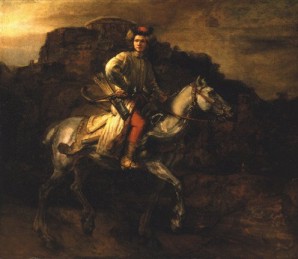

What difference does it make whether Rembrandt or a follower painted The Polish Rider, as long as it still looks beautiful? When scholars burden us with arguments, is it only to dull our senses and certify some dealer's prices? Is an editor at Artforum right when she insists she never reads press releases? I think not, and to explain why, I am going to deny the very premise that there is appearance or beauty on the one hand, history or interpretation on the other.

Sure, the intellect can often denigrate beauty, even ruin it entirely. The threat goes far beyond our respect for art, right to its existence. At least unfamiliar followers of Rembrandt are still painters, and their work is still art. But when critics claim that a row of oversized Campbell's soup labels can be art, they imply that something else—say, something in the supermarket—might not be.  If that sounds a little too much like a cause for celebration, try turning our merry critics loose on a Native American tapestry or an African ritual object. Will it be art, decoration, both, or neither? How about its knock-off behind the furniture display at the mall?

If that sounds a little too much like a cause for celebration, try turning our merry critics loose on a Native American tapestry or an African ritual object. Will it be art, decoration, both, or neither? How about its knock-off behind the furniture display at the mall?

The ability of the mind to establish value in old colored fabrics and aluminum cans is remarkable. At the very least, it reminds us that art is a human creation, and that alone gives it meaning. However, I want to leave tough philosophical questions about the nature of art and vision aside right now, much less how theory holds up to blogging and Twitter. My goal is to plead for the beauty that the critical intellect can bring alive for us, even when its words sound difficult and obscure. Constructive criticism can help artists, too, to sort out contemporary trends and past masters. Together, we can talk like a critic.

Seeing beauty for the first time

When we classify things and write catalogs, it is our way of arranging in our heads what we see, and it allows us to see more. A botanist can be so much more sensitive to the beauty and variety of plants than most backyard observers—and more aware of how that beauty and variety hinge on the smallest detail. Even a bored, hurried city dweller like me can be made to see more than just one green patch after another and to relish the difference.

Science does not have exclusive insight into nature, of course. Art, too, inspires us with the wonder of living things. All the same, both work by forcing us and, ultimately, training us to see. As Yogi Berra said once, you can observe a lot just by looking.

For the same reason, it always helps to decide who painted something: we can then see more in the painting. In ordinary language, the word "connoisseur" has both connotations—of aesthete and scholar making attributions. Artists most committed to beauty for its own sake will take added pleasure when someone sees their special style in something they did, and the viewer takes much the same pleasure in the draftsman's art. Now, it should be said that much of this applies only to art from periods in history that did think of a copy as inferior to the original and did have the concept of a forgery, rather than simply a skilled tribute. But then learning who made the work and when will still shed light on what it has meant, both in its own time and today.

Several generations, myself included, have been turned on to painting by reading Bernard Berenson on the Italian Renaissance and Erwin Panofsky on the Northern Renaissance. Both, writing decades ago, in a sense created artistic personas out of a mass of art and a scarcity of historical records. Sometimes it meant chucking out the losers, but often it meant appreciating a wider range of different styles—and appreciating them more deeply.

The best researchers have often been the finest teachers, because they could share with their students the pleasure that took them to the cutting edge. Thanks to teachers like these, I can appreciate both the delicacy of Jan van Eyck or his older brother Hubert and broader streaks of shading in Petrus Christus, his close follower. I can thrill again to angular complexity of an influence on them both, Robert Campin. I can re-experience Giotto's innovations in debates over who painted what might be his earliest frescoes. Now that I see Titian in light of his predecessors, I no longer write off his work as a lot of out-of-focus, overweight women. I can marvel that he somehow held in his hands both the grandeur of the High Renaissance and the subtle color and light of Venice.

Sometimes, deattributing an artwork or an attribution driven by money does make it look a good deal worse—does entail serious value judgments as an essential critical role—and that can be good, too. Over and over, once a forgery is uncovered, we no longer understand how we were ever taken in. We suddenly see all those differences created by a lesser artist in our own time. We can even see the distinct impulse that went into building a collection in the past.

Letting beauty be strange

At other times, knowledge makes the things we enjoy look stranger—without our enjoying them any the less. A psychologist or historian of chivalry can say how childhood and culture determine who and how we love. A physicist or biologist can explain the emergence of life on a different level. Still, we are in love after all that, and explanations need not make us discount experience. We may see it as less innocent, but the change can be strengthening as well as chastening. Who said innocence is so great, especially in love?

When we let ourselves imagine a loss of beauty, we really are speaking about just that added strangeness, and art thrives on it. I have allowed myself to use beauty too complacently, as a catch-all for the pleasures we take in appearances, but it must be an unfamiliar kind of beauty indeed. Art does not pander to our preference for pretty pictures and tabloid shocks. That refusal is the explicit stance of much modern art; it is why we sometimes hear, misleadingly, that real art is ugly. Artists, however, have always looked without flinching at the banality of life and the terror of death. In his last years, Titian even imagined himself as the satyr Marsyas, being flayed alive by the gods.

Probably the need to work at understanding is most obvious in the older masters, which is why their galleries are visited so infrequently. When a Renaissance painting contains a flower from the New World that had not yet reached Europe, no one wants to fuss over such arcane detail, even though knowing that it was added later might bring the the period's conflicts and passions to life. Even a painting that seems to go down as easy as The Polish Rider poses an obvious problem. It might have been easier to decide who painted it if we could reach agreement on what exactly was painted. Whatever it was, it mattered enough to Rembrandt and his studio to inspire a great work, so I would not be too sure that it no longer matters for our admiration.

Because the ideas behind art of past centuries seem more remote than a period film, they make us face how much we assume when we pretend today simply to look. The need to interpret contemporary works it is just as pressing, precisely because their assumptions are so close to us as to be invisible. When we have achieved enough detachment to decide confidently when geometric abstraction or political art is more than a hoax, we can dispense with the arguments and books, but then we shall probably no longer need the art.

The need for interpretation is most severe of all for those decades in between the Old Masters and the art of today, when the art has become all too familiar. We enjoy Impressionism, but we can easily miss the powerful emotions that produced it, respected it, and denounced it—or the overwhelming effect it had on early Modernism. Those matters are mere history; they hinge on long-gone trends in genre, style, and technique, the society being depicted, and the politics of the French art world. But they led viewers to do more than hang reproductions over their sofas; they caused people to risk their careers. By rediscovering those issues, we can recover some of the emotional response that got Manet to be caricatured in newspapers or sent Cézanne back to contemplate his mountain year after year, and we also gain by learning about other artists, especially women artists, whom the easy stories long overlooked.

Seeing our stake in beauty

Naturally only the ideal scholar, free of economic motives, never lets attributions stand in the way of admiration for art. The Dutch Rembrandt committee is biased to keeping the artist a genius in the very age of Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Hals, and so it often tries to assign unsuccessful art to Rembrandt's workshop. But when the committee does not—as in deattributing a painting as popular as The Polish Rider—it can help us grow to enjoy lesser talents in the Dutch century, where before we might have simply dismissed the works as bad or unfinished Rembrandt. It does not put them on their own pedestal, along with Romantic notions of the solitary, authentic genius. It helps place even originality in its perspective.

But admirers of beauty for its own sake let their personal motives from destroying art's emotional precision just as often. It is what we mean when we call something sentimental, and it is as reductive of art—as much an irritable reaching after certainty—as any scholarly thesis. Most of the time, when one side accuses the other of being anti-intellectual, while the other side complains about willful obscurity, both are correct.

We should value anyone who speaks about art simply and still says something. I myself would love to be clear and knowledgeable enough to reach both sides when I write, and I bet I lose both instead! For all that, however, we must learn to live with difficult ideas about art as well as direct expression. There is a time and a place for both.

I spent many years learning to read science and to look at painting because scientists and painters themselves had spent centuries refining their expression. Science and art needed that time, in order to make their point as richly and as economically as possible. We should not expect such marvelous languages to let themselves be spoken too harshly or too quickly.

In our time, the very distinction between supposed plainness and sublime difficulty has broken down. Modern art tries to be stripped down, but it still has many people puzzled. Scientists have an annoying habit of talking about simplicity, when they mean that matters boil down to two or three equations that plebeians cannot hope to understand. Words like plainness and simplicity may still have meaning, but life got complicated, and it necessarily became harder to say just who is conning whom. As so often in life, however, I believe that the con artist will generally be the one professing the greatest innocence.

Recovering beauty for ourselves

As philosophers have often stressed, there is no such thing as pure observation or "just looking," free of exactly this kind of difficulty. Everything we are and everything we perceive is caught up in what we know—our cultures, our languages, our prejudices, our teachers, our hypotheses, and our love. I think that this is what makes art so important: when it most seems to copy nature, it in fact sees nature as something—and, when the artist is really moving to us, as something we had never fully known before.

In the end, scholarship cannot spoil our sense of beauty, because it is still up to our own sensibility to agree. Even critics have fragile moments, and critical jargon, too, is a refusal to think and to look. When a museum reframes Michelangelo, Michelangelo drawings, Diego Velázquez, or the crossroads of Modernism, we can turn our backs—or cry out at the politics of attribution. For what it may be worth, I do not like The Polish Rider quite as much as the Dutch committee—or, for that matter, the general public—but I think it is by Rembrandt.

Beauty and the intellect are inseparable, and art relies for its very mystery on a mixture of both. Along with Shelley, we owe a hymn to intellectual beauty.

Rembrandt's The Polish Rider has its home in The Frick Collection. A related essay returns to why art takes words and not just looking, while another asks what happens to an art critic on lockdown.