Not So Critical Theory

John Haberin New York City

Songs for Sabotage: The 2018 Triennial

Being: New Photography at MoMA

Scenes from the Collection: The Jewish Museum

The 2018 Triennial opens with playground equipment, but it is not just playing around. The New Museum calls it "Songs for Sabotage," just to let you know. But then, despite its share of terrific art, neither will it have you singing. It is too busy taking on the tools of global capitalism and oppression—and that means you.

Like its title, the triennial is at once strident and slightly off-key. Almost everything harps on colonialism, racism, and globalization. Michel Foucault might have written the wall labels personally.  Someone is singing, quite credibly at that—an aria from Puccini in a solemn concurrent performance off the lobby, by Alexandra Pirici. Otherwise expect only a dull hum. Lydia Ourahmane has treated the grand stairwell to speakers, peeling paint, and deteriorating plaster.

Someone is singing, quite credibly at that—an aria from Puccini in a solemn concurrent performance off the lobby, by Alexandra Pirici. Otherwise expect only a dull hum. Lydia Ourahmane has treated the grand stairwell to speakers, peeling paint, and deteriorating plaster.

Too often, curators have been talking the talk, only to produce a dull hum. I still believe that art takes words. I have delved as best I could into critical theory and, sure enough, Michel Foucault. For the triennial or the latest edition of "New Photography" at MoMA, though, it pigeonholes art as politics. Even with "Scenes from the Collection" at the Jewish Museum, it becomes a mechanical gesture and a distraction. Their art, though, has a way of fighting back.

No playing around

The elevator at the New Museum Triennial opens onto a single swing, by Diamond Stingily, weighted down by a brick and with a ladder to nowhere. Its title, E.L.G., stands for "evil little girl" and sounds like "elegy"—but do not ask what evil or an elegy for whom. The African Americans portraits behind it glitter, but Wilmer Wilson IV has covered all but the faces and hands with staples, as if too weary to let them shine. To the left, Athenians join in protest or run free into the light, but for Manolis D. Lemos Dusk and Dawn Look Just the Same. To the right, paintings by Gresham Tapiwa Nyaude look more exuberant still, but with the enforced smiles of Zimbabwe's state media. Balconies may evoke privilege, but Tiril Hasselknippe in sharp-edged steel takes no prisoners.

The entire cast is young—maybe not "Younger than Jesus," like the museum's first "generational," but not by much. It is out for sabotage, much like the second triennial's "Ungovernables" or "Open Call" at The Shed. Its large paintings and installations put visitors at the center of global action, much like the third version's "Surround Audience." It is focused but diverse, with just twenty-seven artists from nearly as many countries. Even a lifelong American, Matthew Angelo Harrison, preserves West African relics in automotive clay and resin. The sole Brit, Hardeep Pandhal, recalls his Sikh parents and black slavery in Scotland.

This is serious business, but also brash and colorful. Set the wall text aside after having absorbed what you can, and it might even be fun. It can be a roller-coaster ride, like the one that Song Tan conned Chinese naval officers into taking. It can admit doubts along with pride and pleasures—like knives among medicinal plants for Dalton Paula, cartoon images of African Americans by Janiva Ellis, or memories of a life before blindness from AIDS by Manuel Solano. With Shen Xin's video of a daughter comforting her mother and a monk goofing off, it can be anxious, silly, or both at once. What it cannot do is stop begging you to take it seriously.

You may grow tired of trying. Chemu Ng'ok's portraits of hugs and braided hair may cry out for the "decolonization of education" and "self-esteem for girls," but you might lose patience with their unalloyed good cheer. Daniela Ortiz reconceives statues of Christopher Columbus, like the one in New York's Columbus Circle, as cartoon pottery on behalf of cartoon monuments. Clan Dayrit maps Philippine military bases, agribusiness, mining, and "landlessness" as "civilized society," but you may get the message all too soon. Tomm El-Salah adds acrylic hints of nature and iPads, but you may never see them. Julia Phillips fashions vintage tools for observing, stimulating, and beating human bodies, but which is which?

Their very earnestness glides over specifics. Do not look for breaking news of terrorism, the refugee crisis, right-wing intransigence, or climate change—although Violet Dennison makes haunting shapes from sea grass. And some things never do add up. Wong Ping treats fairy tales as "adult parables," but you may see only a video game. Anypam Roy supports India's communist party, but he might just as well be mocking it. Claudia Martínez Garay confronts abstraction with agitprop, but what does that say about either one?

Can art and the artist reinvented still confront propaganda—or surpass it? The curators, Gary Carrion-Murayari and Alex Gartenfield, shy away from the irony needed to encompass both. Art cannot help playing and protesting anyway. KERNEL lays out a fearsome pile of machinery and Zhenya Machneva a comic-strip socialist realism, and the fears and the comedy win out over the machinery and history. Haroon Gunn-Salie fills a room with seated black bodies missing their heads and chairs, like backs for Magdalena Abakanowicz, as if kneeling for a beheading. The show could learn from their arrogance and humility.

Being there

I recognized just one artist in "Being," as befits a survey of "New Photography." Lucy Gallun at MoMA has chosen seventeen photographers from eight countries—and, for those annoyed that just five dealers have so many artists in museum retrospectives, from as many Lower East Side as Chelsea galleries. Even the one I recognized makes a point of being hard to know. Paul Mpagi Sepuya uses photocollage at once to display and to hide his studio, his sources, his body, and his sexual orientation. The rest, too, go out of their way to mess up that theme of being. Who can say when they are showing off—and when they are decrying identities imposed by others?

Its theme burdens the biennial with wall text about the "formation of communities" and "gender, heritage, and psychology." Still, even the weakest and smarmiest contributors have their doubts. Carmen Winant covers two walls with women in labor, with the proud title My Birth, but they are still anonymous found images. Huong Ngô and Hgông-An Truong display family albums, but for two distinct families, and their Vietnamese heritage is all but lost. Shilpa Gupta logs Indian immigrants who have changed their names, but as little more than a landscape in the process of growth or destruction. Matthew Connors captures hesitant gestures and leisure time in North Korea, for a generation strangled by official dreams of paradise.

Diversity notwithstanding, they favor much the same strategies. Each device serves to hold identity at a tantalizing distance, starting with masks. Connors includes one, in reverse, while Sofia Borges finds them everywhere in the clay and stone of archives and museums. Yazan Khalili simulates an app with open windows for "all the masks that disappeared from our lives." Not that their disappearance allows him at last to shine. He speaks, too, of "the pain of not being recognized by the thieves who stole our faces."

Diversity notwithstanding, they favor much the same strategies. Each device serves to hold identity at a tantalizing distance, starting with masks. Connors includes one, in reverse, while Sofia Borges finds them everywhere in the clay and stone of archives and museums. Yazan Khalili simulates an app with open windows for "all the masks that disappeared from our lives." Not that their disappearance allows him at last to shine. He speaks, too, of "the pain of not being recognized by the thieves who stole our faces."

Clothes, like masks, can serve as covering or costume. Aïda Muluneh dresses in bold colors, even in otherwise black-and-white prints, but her Mourning Bride looks more like a shrouded corpse. Andrzej Steinbach has young people pose in sweats and fashionable black—and then switch clothing. Sam Contis has what look like film stills from the nowheresville of California adolescence. Stephanie Syjuco uses patterned prints for a parody of anthropology. She also mimics passport photos for her journey into the present.

Their color and fragmentation reflect still another strategy, image manipulation. B. Ingrid Olson revels in it, making identity into a light show, but it does not require Photoshop. Those museum shards from Borges glow in an otherwordly light, and a man on horseback for Harold Mendez becomes a ghost without a name. Em Rooney hand paints one double portrait. He uses frames and green leaded crystal for distancing as well, for photos of an unnamed protest march or a horror movie. Props for Joanna Piotrowska place her actors in danger, most of all when they are at play.

The greatest distancing of all may come with their entry into the museum. They know that, once inside, they will have familiar company. Muluneh borrows from Gordon Parks for her double self-portrait in a school bus, a girl stretched out on the grass for Contis echoes William Eggleston, and all those untitled film stills owe plenty to Cindy Sherman. Adelita Husni-Bey tells her class that it is taking part in a workshop on the museum's future, a future that is theirs to create. That future is bound to include critical jargon and identity politics. Neither one, though, can kill this selection's strangeness.

Making a scene

I had a dream about an artist, but I never did catch his name. He might have been with me the day before at the Jewish Museum, for "Scenes from the Collection." Like me, he may not often reach the third floor, especially in the dead of winter—but he had to admire its open and flexible renovation, with easier access and more sunlight. He had to admire, too, the more than six hundred selections, including art, ritual objects, and testimony to history. They sure look like things rather than scenes to me, but the title refers to the display's seven sections. Works rotate in and out, the better to refuse a fixed canon and to show off the museum's holdings.

No doubt my companion appreciated the devotion to art, including two paintings by Lee Krasner alone and early work by Eva Hesse, Mark Rothko, and Louise Nevelson—not yet abstract but already matters of life and death. He would recognize in William Anastasi the frightening power of labels, here the lowercase jews, but he must have been surprised to see Morris Louis wrestling with a Jewish star. He might wonder at Chantal Akerman on video, who shifts from her usual frank confessions to a headlong course across the desert. He could savor the occasional pairing, like a golem by Robert Wilson alongside a wedding dress for a Sephardic bride. He had to be touched by stereographs and drawings from the camps. He might even, like me, have taken a photo by Candida Höfer as a reason to make a Philadelphia synagogue, a late design by Frank Lloyd Wright, a must-see.

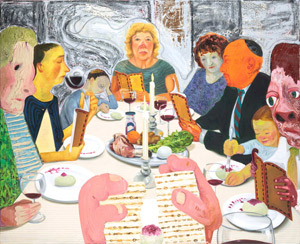

He might have forgiven the show's most popular room, for sitcoms, and Nicole Eisenman shares their awkward family comedy in painting a Seder. He could accept well enough a shiksa like Cindy Sherman in biblical dress or a portrait by Kehinde Wiley alongside an equally ornate Torah ark from, of all places, Sioux City, Iowa.  He still treats his sitters as tabloid celebrities, but he was pursuing the lives of African Jews. My unknown artist might have had a harder time with a wall label about Deborah Kass that hones in on her creepy eyeglasses with human lips—but never cites Jasper Johns as a source. He might have rebelled outright at boasts of a long-time commitment to recent art that never mentions a 1966 exhibition at the Jewish Museum, "Primary Structures." As director back then, Kynaston McShine made it New York City's museum of contemporary art.

He still treats his sitters as tabloid celebrities, but he was pursuing the lives of African Jews. My unknown artist might have had a harder time with a wall label about Deborah Kass that hones in on her creepy eyeglasses with human lips—but never cites Jasper Johns as a source. He might have rebelled outright at boasts of a long-time commitment to recent art that never mentions a 1966 exhibition at the Jewish Museum, "Primary Structures." As director back then, Kynaston McShine made it New York City's museum of contemporary art.

But no, what stopped him dead were the divisions, or scenes. Constellations, taxonomies, and accumulations defy anyone to tell them apart. Signs and symbols or personas seems left over from the heyday of "theory," when it might have had bite, while masterpieces and curiosities could accommodate anything. Television and beyond seems to forgot the part about beyond. So he decided to take them as titles for dream paintings, four for each section, in order to make a scene. They are thick, gestural, and surely his own, but practically identical, much like the themes. Their bright colors add up to a dull brown.

And they instantly caught on, starting with social media. People in my dream did not so much demand an exhibition as assume that they were part of the show all along. The museum struggled in response to include them, if only online. Artists returned to their usual rants against a loaded art world that refuses to allow "just looking." Others deplored its descent not to artspeak but to martspeak. I have made that my theme before.

Soon enough, the ironists weighed in. The near identical works only reinforce Postmodernism and its critique of originality, and besides I dreamed them up. They depend for their sudden celebrity on attaching themselves to jargon after all. Only thus could one ignore their tedium. Rather than holding a mirror up to nature, they have entered a hall of mirrors. They know too well that Jews more than anyone know about irony and the life of the mind as well as beauty, suffering, and responsibility—and the scenes from the collection lay claim to them all.

"Songs for Sabotage" ran at the New Museum through May 27, 2018, and Alexandra Pirici through April 15, new photography at The Museum of Modern Art through August 19. "Scenes from the Collection" at the Jewish Museum is ongoing. Related reviews look at past and future New Museum Triennials, including "Younger than Jesus," "The Ungovernables," "Surround Audience," and "Soft Water, Hard Stone." New Photography 2023" in turn comes Lagos.