Visionary Pleasures

John Haberin New York City

Jean-Jacques Lequeu and the Enlightenment

Architecture, Theater, and Fantasy: Bibiena Drawings

You may have trouble seeing Jean-Jacques Lequeu, the French architect, as heir to the Enlightenment. Indeed, you may have trouble seeing him as an architect. For the Morgan Library, make that "Visionary Architect," as if he had his eyes on the heavens, but Lequeu more often looked the other way.

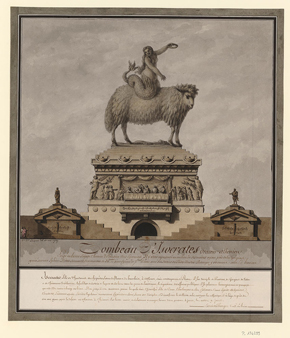

There he is on paper, yawning or sticking out his tongue, whether at Enlightenment ideals of progress, himself, or you. There he is again, with his eyes on less savory subjects, like the bare buttocks of a "white savage." He had his Civil Architecture, but it does not look all that civil. It has room for a combination tavern and "hammock of love"—and a brothel discretely labeled the Temple of Silence.  Even when he imagines a tomb for a fabled Greek orator, its elaborate base could well parody classicism, and Lequeu tops it off with not a hero on horseback, but a mermaid riding a sheep. Yet he devoted himself to his visions for a tormented half century, until his death in 1826.

Even when he imagines a tomb for a fabled Greek orator, its elaborate base could well parody classicism, and Lequeu tops it off with not a hero on horseback, but a mermaid riding a sheep. Yet he devoted himself to his visions for a tormented half century, until his death in 1826.

Speaking of visions, my first thought when it comes to Bayreuth is Richard Wagner, and my first thought when it comes to Wagner is the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. His ideal has influenced everything from German opera to Broadway theater, where Richard Rogers and Oscar Hammerstein II sought to unite book, lyrics, music, and dance in the service of musical drama. So why not architecture? As it happens, Wagner worked in Bayreuth, in Bavaria, in no small part because of the Margravial Opera House, designed more than a century before him by Giuseppe Galli Bibiena. But Giuseppe was just one leading light in a spectacularly creative family. It had its own dreams of a higher unity at that, on view in "Architecture, Theater, and Fantasy" at the Morgan.

Enlightenment theater

You may hesitate to see a predecessor of Jean-Jacques Lequeu like Giovanni Battista Piranesi as a creature of the Enlightenment either, not when he pushed his architectural fantasies to the point of prisons or ruins. Yet Piranesi knew the classics cold, and his dungeons and towers serve as a compendium of them, just as Enlightenment scholarship had its great Encyclopedia. Nothing escaped its attention, much as Lequeu's self-portraits add up to a compendium of humanity—"reflecting," "squinting," "pouting," "crowing," and "preening." Lequeu meant his Civil Architecture as a textbook, with a sheet for drafting tools, including brushes of all sizes and to all purposes. When he sketches a portrait bust, it is (deep breath) his New Method Applied to the Elementary Principles of Drawing, Tending to Graphically Perfect the Outline of the Human Head by Means of Various Geometric Figures. The "ideal smile" comes with a protractor to take its measure.

Enlightenment theater often verged on Romanticism, as also with Claude Gillot and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, without losing its aim of rigor. Like late Modernism, it asked to reconstruct art, architecture, and society from their elements. When it looked to the ancients, it sought not a rebirth like the Renaissance, but a vocabulary and a point of origins. Form could follow function, in architecture parlante, or "talking architecture"—only it could also talk dirty. When Claude-Nicolas Ledoux designed yet another house of pleasure, he gave it the shape of a penis. When Lequeu imagines a chicken coop and dairy barn, it has sculpted udders.

Born in 1757, he had every claim on classic architecture. He started in the studio of Jacques-Germain Soufflot, who designed the domed Pantheon in Paris, completed in 1790. It served Ledoux as a model for his Temple of the Earth—a planetarium, with holes punched in the great dome for stars. He did his best to navigate France's shifting politics, and who knows what he believed in his heart? He had his Temple of Equality during the Revolution and an aristocrat in shackles, but a note on the back of one drawing calls it a way "to save me from the guillotine." In 1821, during the Restoration, he pays due tribute to the baptism of a royal grandson.

Still, today's textbooks fail to mention Lequeu for good reason: he had little to show for his pains, least of all architecture. If The Great Yawner wears the cloth coat and bowler hat of a bored and overworked bureaucrat, he found work under Napoleon only as a cartographer in the land registry. Naturally his maps keep up his obsessive geometry and detail. He found still less favor under the monarchy, which sent him into forced retirement. He responded by giving more than eight hundred sheets to what later became the Bibliothèque Nationale de France—the source of loans to the Morgan.

Even there, his work had trouble fitting in. White Savage ended up in the library's "hell" for pornography and rebellion. So did a bacchante shoving a primitive wind instrument toward, if not up, his arse. And these, too, make it hard to know what he desired. Were they confessional, confrontational, or both? Figures of dubious gender might be further studies in psychology or just Lequeu's ways of getting off, but they have fresh relevance in light of LGBTQ art today.

The show's title plays on another aspect of his time, the "visionary architecture" of Ledoux and Etienne-Louis Boullée. Still, the curators, Jennifer Tonkovich with Corinne Le Bitouzé and Christophe Leribault of the Petit Palais in Paris, stress just how hard he worked on his visions, including lengthy annotations. His sketches take particular pains with shadows—the very point of those drafting tools. He also tried to make the visions practical, right down to a river of lava feeding a Temple of Divination with its smoke. "Work," he wrote, "is often the father of pleasure," and he worked hard all his life toward ambiguous and unrealized pleasures.

Total theater

You may not think first of architecture as you enter the Morgan—or you may wish you could forget it. Its 2006 expansion, by Renzo Piano, shunts to the side J. P. Morgan's stone mansion in favor of a barren space to sit for coffee. And Bibiena drawings have the small gallery right off the lobby, one year after Lequeu upstairs. That should already have you thinking about conflicting ideals, in Modernism's "form follows function" and late Baroque fantasy. Yet the family cared about function, too. It wanted a stage adaptable to almost anything, and its architecture incorporated one illusion after another to enable theater's illusions as well. Nothing is what it seems, and nothing is ever enough.

For the Bibiena family, a total work of art runs to one huge total. Far be it from me to disentangle thirteen names and four generations, but a family tree comes to the rescue on the way in. Giovanni Maria Galli, born in 1618, moved to Bologna to pursue painting, taking his home town in Tuscany as his family name. Things get going, though, only in 1701, as his descendants begin to compile a vocabulary of architectural form. They agreed on almost everything, right down to a fluid but precise drawing style in pen, ink, and brown washes. Artists are all but impossible to tell apart.

For the Bibiena family, a total work of art runs to one huge total. Far be it from me to disentangle thirteen names and four generations, but a family tree comes to the rescue on the way in. Giovanni Maria Galli, born in 1618, moved to Bologna to pursue painting, taking his home town in Tuscany as his family name. Things get going, though, only in 1701, as his descendants begin to compile a vocabulary of architectural form. They agreed on almost everything, right down to a fluid but precise drawing style in pen, ink, and brown washes. Artists are all but impossible to tell apart.

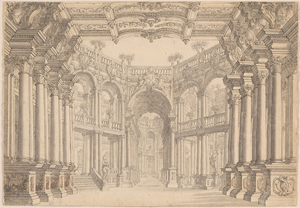

The Morgan's photo of the Bayreuth opera house, designed in 1738, has its own all-encompassing panorama. Just try to disentangle seating below from a ceiling painting above—or colonnades to either side. The stage seems to recede into infinity. In drawing, too, the family favored scenas per angolo, or angle views, but with room as well for tunneling perspective. Here, too, architecture reflects an understanding of theater. It leads the eye in every direction, while the audience remains seated. It becomes an out-of-body experience.

Architectural elements build on those conflicting perspectives. Barrel vaulting, arches, and mirrors both frame and mimic physical space. Decorative elements include statues, carvings, and twisting columns. Naturally these are Corinthian columns, the fanciest of the five classical orders. A bit above its leaf-like decoration may come yet another carving as well. If this has you thinking of Rococo fancies at the Frick, Jean Antoine Watteau had an abiding interest in music and theater, too.

For all their liberties, the family chafed at restrictions. Ferdinando complained openly of architectural conventions and linear perspective as constraints—not to mention the need actually to build something. No wonder studies for architecture mix with independent capriccios, or caprices. When Carlo sketches a Parisian hotel or Giuseppe a palace fit for a prince, are these subjects for architecture or its inspiration? Drawings confuse indoors and out as well. One might be standing at the center of a Roman plaza or a theater itself.

When it comes to theater, the family had one success after another, from Lisbon to Vienna and from Stockholm to Saint Petersburg, and its outlook was broadly European as well. Sailing ships, in a stage design by Francesco, look right out of the golden age of Dutch painting—and a many tiered prison by Antonio right out of Piranesi. Wagner's orchestra outgrew the Margravial Opera House (named for the Margrave Frederick, brother-in-law of Frederick the Great), and he ended up designing his own. Still, the madness spoke across centuries to Jules Fisher, the lighting designer for Hair and other Broadway productions. The drawings are his collection, including a promised gift to the Morgan. The hippies on a nearly bare stage for Hair might be one part Bibiena fancy and one part Renzo Piano Modernism.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu ran at The Morgan Library through September 13, 2020, "Architecture, Theater, and Fantasy" through September 12, 2021.