The Cold Shoulders of Giants

John Haberin New York City

The Dean Collection: Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys

Marcus Leslie Singleton

What makes for a thoroughly dispiriting exhibition? Not just weak art or forced curatorial themes, but the smell of money. You could, after all, find that you were mistaken about the first two or, if not, waltz right through and forget it. The smell of money is harder to escape. It clings to your senses and to the entire state of the art.

You know the stench from museum displays of private collections, the owners angling for their name on the wall, the museum for a gift. You know it, too, from shows of fashion and celebrity, with no more relevance to art than the ticket sales they hope to achieve. Now the Brooklyn Museum manages both, with the Dean collection—from the family name of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys, stars who know how to make music and how to dress for it. You know who they have in mind when they call the exhibition "Giants."  And yet, for all that, the artists are names as well, with large works that themselves might hang beside giants. It could serve as a full-scale survey of contemporary black art, a lively one at that, if you do not mind the limits of stardom, sparkle, and trends.

And yet, for all that, the artists are names as well, with large works that themselves might hang beside giants. It could serve as a full-scale survey of contemporary black art, a lively one at that, if you do not mind the limits of stardom, sparkle, and trends.

In much the same spirit, a portrait by Marcus Leslie Singleton has the widest, whitest eyes that you may have ever seen. Dee Dee would be charming enough from that alone and her broad red smile, even were she not leaning so disarmingly toward a table set with flowers. Their white and the deep blue of their stems and flowerpot erupt into a medley of white and blue in the sky, the leaves hanging down by her head, the seeming floral crown of her hair, her patterned dress, and the glints of color along her nose. But who is she? From the title, you might not know that Dee Dee is the black artist's mother, which seems only right, for she deserves a life of her own. She opens a show in Chelsea in which every portrait is a study in relationships.

Stardom and community

Collectors, fashion, and celebrity need not rule out diversity—not to judge by past shows in Brooklyn of Virgil Abloh and Spike Lee. And these collectors know how to stick up for blackness and how to please. The curators, Kimberli Gant with Indira A. Abiskaroon, open with a glittery assemblage by Ebony G. Patterson that could pass for a store window at Christmas, were it not for the pink background and black children's faces. Then the giants themselves kick in, with their BMX bikes and Yamaha piano, painted with Freedom and Love. Bikes return later, too, in paintings of wheelies by Amy Sherald. And then the collectors pose for Kehinde Wiley, like heavenly beings in Wiley's oval of flowers.

All fashionable, well, and good, but those black faces belong to real children and wheelies to the street. Forget the heavens this once. Wiley made his name taking his flattery to black men on the street. Here he also paints a woman lying down, on a still larger scale. If Beatz and Keys bring their precious possessions, they want you to relax, too, amid Bang & Olufsen speakers and soft black chairs. This is not, they are saying, just about them.

It is about people and politics, even if it does land in the museum's Great Hall. The collectors pose again for Jamal Shabazz, in a photo hung with Eldridge Cleaver by Gordon Parks. They trace their ancestry to Africa, with a street scene from Ernie Barnes in 1957 and abstractions by Esther Mahlangu based on patterns that one could mistake for Native American. They have crossed the sea, like Barkley L. Hendricks to Jamaica for quaintly framed landscapes. Shabazz and Parks face off again in a long hall—the first for some of his most politically charged images, the second for the streets of Brooklyn. They could almost be debating what "Giants" is all about.

More often than not, it is about home, on or off the streets. Deana Lawson and Toyin Ojih Odutola have figures in suggestive interiors—although Lawson's just happen to include a naked "Soweto queen." Meleko Mokgos devotes a full room to families in Botswana. He says that he wants to know "how the subject is constituted," but (postmodern rhetoric aside) he is in search of community. Fancier matters, like conceptual art and new media, take second place. Lorna Simpson places her photos above text for future and past, perfect and imperfect, but the operative word comes first, the present.

Still, "Giants" sees them all as stars. even as the upcoming "Brooklyn Artists Show" sticks to unknowns. Mickalene Thomas, Kwame Brathwaite, and Nick Cave have their undying flattery and glitz, while Lynette Yiadom-Boakye brings her camera to the dance. Derrick Adams and Nina Chanel Abney span four canvases apiece. Politics itself takes a back seat, although portraits by Henry Taylor and Jordan Casteel plead for food and just plain respect. When Hank Willis Thomas makes a geometric abstraction from worn prison uniforms, he could almost be erasing it, along with one by Odili Donald Odita to its left. When his silvery arms cross in a worker's protest, their sheen reflects on the entire show.

Still, "Giants" comes down to its collectors. Like them, it is self-assured and catchy. Like them, too, it returns again and again to the names and trends you know. If portraits of pomp and circumstance pass over a still greater adventure, perhaps the artists themselves could suggest alternatives. Meanwhile, Arthur Jafa all but knocks down the entire edifice. A truck tire laden with chains and suspended like a pendulum is heading for you.

Family and friends

Dee Dee speaks loudly of the eternal awkwardness and pleasures of family and friends. She has held onto an image of herself in a photograph—and he takes pride in painting it as testimony to his affection. Still, its reserved title attests to the distance that remains. Photos always do, even selfies, and the closest figure in a group portrait picks up his own camera to shoot right back. A family portrait makes room for nearly twenty figures standing or seated around a table set for a celebration, but not with the varying degrees of closeness that, in a royal family by Diego Velázquez, tempt one to ask just who loves whom. And will the lonesome turkey really feed them all?

Some look downright sullen, and Marcus Leslie Singleton leaves it open whether that arises only from his chosen limits as an artist. He adopts nearly flat fields of color for dark skin, bright interiors, and sunlit streets, akin to folk art. That and a focus on portraiture have become something of a norm for African American artists like Demetrius Oliver, Titus Kaphar, Sherald, Thomas, Wiley, and the entirety of "Giants." Singleton all but picks up where Henry Taylor at the Whitney left off. If Singleton differs, it is in caring more about relationships and less about putting family, friends, and strangers on pedestals. Dee Dee has the only solo act in the show.

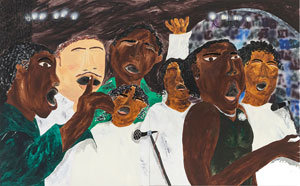

The rest are group portraits, unless you count a still life with no one at all in sight—but even there a close-up of a parent and child hangs on the back wall. Singleton works when he can from photographs, and who does not have a photo of nearest and dearest somewhere on display at home? Most are of special occasions, the kind that bring people together, like a Sunday choir in an excerpt from a photo that brings the faces that much closer to him. Still, what counts as special is up to them. Other kids are just getting together, basketballs in hand. But then the one on a bike could be riding past.

The rest are group portraits, unless you count a still life with no one at all in sight—but even there a close-up of a parent and child hangs on the back wall. Singleton works when he can from photographs, and who does not have a photo of nearest and dearest somewhere on display at home? Most are of special occasions, the kind that bring people together, like a Sunday choir in an excerpt from a photo that brings the faces that much closer to him. Still, what counts as special is up to them. Other kids are just getting together, basketballs in hand. But then the one on a bike could be riding past.

They combine the pleasures and displeasures of the special and the everyday. Singleton shows his affection while preserving a sense of humor and other marks of detachment. Shea Butter Babies has just one true baby, perched on the handlebars of a bicycle like a hood ornament, with protective shielding on her front that reads Fun Time. Then again, the two grown women behind her might be babes of a sort as well. Interiors and houses open onto half-seen rooms with decorations of their own. And whatever are the cars and kids doing parked along the shoulder of a road?

Yet the everyday may lead to transcendence as well, like Dee Dee's riot of flowers. Man's Soul Turning into a Rock promises an epic transformation. Is turning into a rock altogether a bad fate? The soul is himself turning blue, in the company of angels and a man kneeling as if in prayer. Rays from his eye and another man pierce the soul as if bringing it to life. Then, too, the boys by the side of a road are Blue Angels.

The leap from the everyday extends to Singleton's technique as well. It blends oil and oil stick with spray paint, glitter, and glue. Free browns running up and down a wall have little in common after all with outsider art, whatever that means. It speaks of inclusiveness at that. People of color, it turns out, run to all sorts of colors, from near black to near white. One can still doubt whether the world needs yet another glittery young black portraitist and an escape from politics, but he is already sharing the awkwardness and the love.

The Dean collection ran at the Brooklyn Museum through July 7, 2024, Marcus Leslie Singleton at Mitchell-Innes & Nash through January 27.