Post-Emerging Black Artist

John Haberin New York City

Kori Newkirk, Kehinde Wiley, and Demetrius Oliver

Even after a remarkable presidential election, will America ever allow a post-black identity? If it did, could portraits show it? In the last few years, programs at the Studio Museum in Harlem helped to promote the term. Now several artists from those programs have prominent solo shows, with portraiture very much in mind.

Kori Newkirk looks for his subject around the edge of his body, in material things not so very easy to separate from traditional roles. Kehinde Wiley still looks to pop culture for role models and gives them center stage, but now all the way in Africa. Just across the hall, however, the three emerging artists in "New Intuitions" put Wiley's admiration for black males and their poses through the wringer. Last, Demetrius Oliver seeks it in and around the edges of his studio, his camera lens, and the physical universe, and he seems hardly to care what color he finds. All the same, it looks blacker, more elusive, and less like a stereotype the longer he looks.

Is it a portrait of blackness? Can it be? Should it be? If there is a post-black identity, does it allow a photographer to pose his subject? Part of the fun comes in locating the subject in the first place.

Hair apparent

Up at the Studio Museum to catch a new project room downstairs, I had a nice sensation. Needing a breather, I thumbed the catalog from "Freestyle," Thelma Golden's first show as director. How familiar many of its names had become! The museum's perspicacity and, for you cynics, its influence count for some of that. However, this institution has a real commitment to its artists, too, through its residencies and other follow-up shows.

Kori Newkirk is a case in point. Six years after "Freestyle," he returns to the museum's main space with ten years of work. Then he served as an exemplar of "post-black identity," a cool idea that still deserves the scare quotes. Now he is still defining his identity as an artist, and he is doing so by circling back to himself. His small show has five distinct bodies of work. I liked them all, and yet each in its way feels partly unformed. Is it a sign of uncertainty, of an artist's still running in place, or of the "post" now attached to "identity"?

Back in 2001, he worked directly on the wall, in styling gel. The medium has the immediacy of site-specific drawing—and an odor to match. It plays on racial stereotypes, the physical presence of human hair, and the paradoxical absence of an actual body. So does his subject of the time, a surveillance helicopter. Does absence here belong to the nature of representation in art, to the invisibility of black men in America, or to actual flight from the cops? Newkirk's new show starts with the same medium and the same issues, in a drawing of a black Cadillac by the front desk.

Entering, one might be watching him leave one idea behind in search of others. Each in its way seems visually richer, but emotionally and politically more tentative—or more measured. His best-known work, bead curtains strung with artificial hair, recalls the pomade while cutting across a gallery. The curtains show landscapes, perhaps the rural New York of his childhood and the ghetto skylines of Southern California, where he has lived since attending the University of California at Irvine. The translucency of plastic translates into deep, almost flaming skies with a low-tech pointillism that Devorah Sperber with her Mona Lisa in spools of thread might admire. A sense of smell has given way to the sense of sight.

A sense of touch lingers, but the associations have become more elusive. Nothing insists that this is how you picture blackness, unlike images of hair by Lorna Simpson. A third body of work, basketball hoops connected by more black thread in place of nets and poles, has the humorous illogic of Karyn Olivier and her playground equipment and industrial materials or, for that matter, basketball hoops from David Hammons. Clanking chains from parade figures held aloft at night in a short video may also echo Hammons—the latter's video of a black man kicking a can through the streets. The relation of nature and landscape to identity becomes even more puzzling in plastic and neon sculpture of icicles, snowflakes, and sharks. Is he thinking of winters upstate, or is he making whiteness the locus of death, like Melville's whale?

The black body, this time his own, slips in and out of a second video and related photographs. Dressed in only a silvery jockstrap, he bobs in and out of tall grass. At least his bare feet or his shaven head appears, generally when one no longer expects it. The grassland and near nudity, too, may allude either to childhood or to a black stereotype, tribal Africa. The photos, oddly enough, lose the fun and surprises of the video, along with his athleticism. They could be putting out feelers toward another stage in a still incomplete career.

The new black

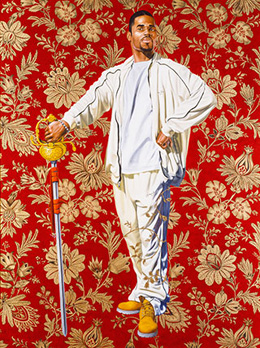

What defines African-American identity, and what unites blackness across continents? Is it decorative craft traditions or a raised fist? Is it testosterone or a global campaign?  Kehinde Wiley has traveled to Lagos and Dakar, where he claims to have "steeped himself" in history and culture, but it has sunk only skin deep. Before he gained attention by turning European painting into a fashion spread for black men, like a dumbed-down version of Barkley L. Hendricks in African American portraits or Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in the Dean collection. Now his art has turned for his answer to "The World Stage," with young Africans, but only their hairdresser will know for sure.

Kehinde Wiley has traveled to Lagos and Dakar, where he claims to have "steeped himself" in history and culture, but it has sunk only skin deep. Before he gained attention by turning European painting into a fashion spread for black men, like a dumbed-down version of Barkley L. Hendricks in African American portraits or Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in the Dean collection. Now his art has turned for his answer to "The World Stage," with young Africans, but only their hairdresser will know for sure.

It sounds like a joke about fashion and a white, downtown crowd's love of dark clothing—Africa as the new black. Like advertising, Kehinde Wiley leaves nothing to a second look, not even when he paints on glass for Penn Station's Moynihan Train Hall. The thinly painted portraits share the hard edges and disposable imagery of slick, disposable magazines. The confrontational poses and glances that avoid eye contact, too, derive from pop stars and fashion models, always with a male attitude. Figures hang out together against brightly colored wallpaper—at most a token appreciation of African tapestry—from which one's gaze runs off like water on a shower curtain. Only a pattern's occasional overlap in front of the sitter defers to postmodern mind games, African tradition, or, heavens, woman's work.

For a year or two now, the Brooklyn Museum has welcomed visitors to its lobby with a grand equestrian portrait. There Wiley inserts a pudgy, bearded man against period wallpaper, in place of Jacques-Louis David, his Neoclassicism, and his dashing Napoleon dashing across the Alps. The appropriation of white heroes and Western art makes a serious point about race in America, but its affirmation goes down way too easily. It repeats Neoclassical dreams of empire, and Wiley's latest work joins globalization in obliterating historical forms—along with holders of a second X chromosome. Does it sound cynical to appropriate while excluding so many? It sounds at best idealistic and self-involved to put those proud few on display without exposing very real scars.

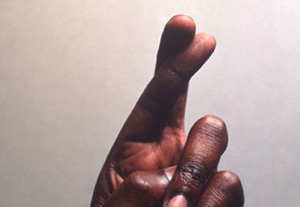

Women notice these things. They also know when discretely to look away. Do they put in question the whole idea of black male identity? Tanea Richardson has even turned the phrase black and male in America into a URL—and the domain registrar reports it unavailable. Richardson joins Leslie Hewitt and Saya Woolfalk as this year's artists-in-residence. None of the art in "New Intuitions" has the rigidity of Wiley's macho heroes, but clenched fists and erections have left their mark all the same.

They might have punched through the floorboard for Hewitt's largest work, while flinging together its broken glass and wood. They might have scrawled her cryptic gouache alphabet of personal objects. One can see these as memory traces, rescue efforts, decomposition, or breakthrough. In her photographs, a photograph hangs on another found board. The architecture frames the art, and the art frames the architecture, but each is fading even as it exceeds the limits of its container. So do Richardson's rude, black fabric bundles, ambiguously supported or entwined in thread, twigs, and electrical cables. Male or female, they do not lack balls.

Woolfalk makes use of both fabric and wood, along with an eye for the absurd. She traps limp, stuffed creatures in a birdcage, in cuddly shades of pink out of Mike Kelley but none of his swagger. The same knits cover ambiguously sexual lumps out of Louise Bourgeois and Bourgeois in painting, and more of it costumes human actors, the inhabitants of her No Place. On video, the monitor surrounded by gilded, slightly sagging totems, she pursues a lengthy anthropology of No Place. A mix of cartoons, huddled masses, and street comedy, it begins and ends like Duke Riley on the New York waterfront, where a forlorn creature first sets out and then packs up her totemic wares, as if uncertain whether her space invasion had found a welcome. Now if only the aliens had it in them to enter "The World Stage."

Self-portrait in a convex mirror

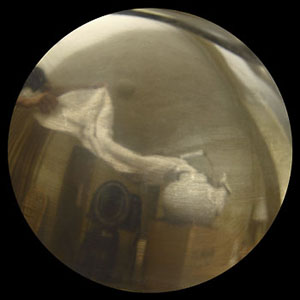

Demetrius Oliver keeps returning to his studio, in search of bigger game. Like most obsessions, the search seems modest at first. The props in his photographs, half obscured by darkness, range from everyday needs to the tools of the trade. The space behind them remains largely empty. For Oliver, though, it holds multitudes.

He must have explored every nook and cranny by now. In "Scratch," as a 2005 artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Oliver set his teakettle on display alongside exactly twenty-four photographs in a single row—one for each hour of the day. Its whistle testified to a mundane existence. How else to stay awake that long? Only his circular format, thanks to a fisheye lens, linked the series to star charts on the same wall. If anything, the charts seem barer still, as well as less urgent.

The constellations return in a solo show, mostly by indirection. Photographs and their curved surfaces still command attention, now freed of a day's earthly rhythms. Their larger scale allows a wider range of shadows and reflections, and it emphasizes the artist's near absence from his own self-portrait. John Coltrane's Interstellar Space accompanies an equally elusive studio tour on video. Parmigianino added a window's distorted rectangle to his late Renaissance Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, but he left no doubt about his subject. When he photographs himself setting up, Oliver depicts himself as still finding his.

Photography has a knack for the gaps in self-portraiture. For all the medium's immediacy, the subjects it records belong to the past, and someone always occupies the far side of the camera. Among other early fall 2008 standouts beside African Americans, Jane Hammond inserts herself into a collage of the last forty years. Elsewhere Ron Diorio brings warmer tones, softer edges, and fewer quotations this time to his computer-adjusted New York. The scenes grow harder to identify but closer to a sense of home.

Like Parmigianino, artists these days often set forth their studio scene defiantly. Think of Kerry James Marshall, Jason Rhoades's CD collection in the 2008 Whitney Biennial, or any number of other overblown installations. By comparison, Oliver remains almost down to earth, even if the edges of the frame reach for the stars. He is not, however, above boasting. The teakettle literally set his life on a pedestal, and the hours defined his personal narrative as a microcosm of existence, much like the twenty-four chapters of Ulysses. Even now, he risks using vagueness as a shortcut to eternity.

For Oliver, an artist's setting up always opens onto something greater. The wide-angle lens serves as a metaphor of a larger vision. Its globe, the fisheye, the planet, and the celestial sphere nest neatly, if artificially, one inside the other. He has exploited its murky outlines before, with hints of violence in earlier photographs at the Studio Museum, in a show of emerging artist. Without the framework of the hours and on a larger scale, Oliver's art has become less conceptual and more visually compelling. Perhaps the connections among his past themes will become more explicit over time as well, or perhaps the disconnections will instead.

Portraiture and posturing

Paradoxes have a way of haunting racial identity. Biologists deny its reality. People cling to it and flee from it. America lets it tear people apart. An American or an African American is, by definition, a political entity. Politics is ambiguously a public and private realm.

But you know all that. I respect Judaism, but see myself as Jewish only insofar as I can respect it—and only insofar as other people lend one an identity whether one wants it or not. I can only imagine the position of an African American. I am hoping that, by the time you read this, the nation will have elected a black man as its president. It will not, however, come without still more of the usual mix of idealism, hope, uncertainty, excuses, politics, prejudice, and pain.

Like politics and race, art is ambiguously public and private—a space of shared media, overlapping audiences, bold gestures, and fluid identities. For that very reason, it attracts censorship and controversy, and political art has continued relevance. Thanks in part to art, in fact, cultural change is possible. Under Golden, the Studio Museum has a reputation for exploring post-black identities. It has not meant that African American art has nothing to do with blackness. It means only that identities are confused and plural even before art gets to them, and then something else happens.

All that sounds hopeful, but it requires a few clichés of its own—and a lot of optimism. Just as others help to define one's identity, artists define their subject, and in turn their subject defines them. Either process also has to remain incomplete, because creating a subject means inscribing it within larger and changing boundaries. The Studio Museum often invites student photographers to draw on classics of the Harlem Renaissance like Winold Reiss and James Van Der Zee, and the museum displays the results side by side. The display at once insists on a canon, gives today's Harlem a fixed past, and disperses it in new directions.

Things get trickiest when artists succeed. Golden and her associate curator, Christine Y. Kim, have given space to emerging artists. In these group shows, no one artist is representative of anything. What happens, then, when they become solo acts? What happens if the solo acts involve not the history lessons and erasures of Kara Walker, in video and spun sugar, and Gary Simmons? What if they amount to portraiture, self-portraiture, and posturing?

Wiley has gained popularity from playing to stereotypes, from the street and popular music, while Newkirk plays with them. Wiley has been posing young black men as pop icons and as characters in Western painting. Newkirk has skipped the portrait's sitter and kept the props. Oliver never even occupies the center of his own self-portrait or his own studio. He sticks to the tools of the photographer's trade, and they open out in all directions. He still cannot quite resist loading his art with more connections than one may ever see, but his work looks personal and evocative all the same.

Kori Newkirk ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem through March 9, 2008, Kehinde Wiley and the artists in residence in "New Intuitions—featuring Tanea Richardson, Leslie Hewitt, and Saya Woolfalk—through October 26. Demetrius Oliver ran at D'Amelio Terras through September 27, Ron Diorio at Peter Hay Halpert through October 31. Related reviews catch up with Kehinde Wiley for his midcareer retrospective in Brooklyn and Wiley's public sculpture.