What Abstraction Left Out

John Haberin New York City

Philip Guston and Wilfredo Lam

No one could accuse Philip Guston of being less than explicit. Who would dare?

This is the artist whose fame rests on a style so simple and legible that it approaches cartoons, and he used it to paint a uniquely American trauma, the Ku Klux Klan. If that brings him closer to jack-booted thugs of every kind, he also painted shoes and boots—piles of them, with soles so hard and thick that they could easily tread on you. The accusations keep coming, and so do the inner demons, just when you may want to tell him to shut up. He could never resist pointing a finger at anyone with the least doubt about what he was doing, including himself.  Nor was he the only one to insist on what the abstract art of his time leaves out. Wilfredo Lam did so loud and clear, without looking out from behind the myths or the masks.

Nor was he the only one to insist on what the abstract art of his time leaves out. Wilfredo Lam did so loud and clear, without looking out from behind the myths or the masks.

Lam does not make it into many a textbook of modern art, but he has shaped textbook accounts all the same. As an Afro-Cuban artist, he serves as a model, and so can the masked figures of The Jungle from 1943. For at least one prominent critic, Michael Leja, they reframe Abstract Expressionism for a time of postmodern diversity. Could the same route lead to his relevance for today? With close to a full survey, a gallery sees a "radically syncretic visual language that challenged the Eurocentricity of Modernism." It is a jungle out there, and a good thing for art.

Pulling the plug

Philip Guston never looked back to the woozy abstractions that made his name in the 1950s. Yet here he was in 1978, with a brushy painting so black and so infused with white and red that it could pass for bold but nuanced monochrome. And here it is again, crossed by a single wiggly white line, briefly thickening in the middle, with no clue to what he might have seen. Curators will not venture a guess, but I vote for an extension cord. As always with Guston, the painting makes a point of its blackness, bluntness, and anxiety, right down to the title, On Edge. Has the painter's power finally gone out?

His gallery is not saying either, more than thirty years after his death in 1980. It has, though, assembled a large and impressive selection from the years 1969 to 1979 alone. It was a crucial decade, starting with a solo show that got even more attention than the first and has earned equal parts anger and admiration ever since. Jackson Pollock, a close friend from his student years and another rebel, had invited him east from LA long before—just in time to launch his "Abstract Impressionism" and a career. Had Guston now turned his back on everything they believed, and was that a good or a bad thing? For many, it put an end to Modernism once and for all.

Lovers and haters alike can miss just how much Guston was one of a kind. The imagery and hints of cartoons link him to Roy Lichtenstein and Pop Art—and the sense of dread to an electric chair by Andy Warhol. Yet he retains a political or confessional edge foreign to an obsession with pop culture, perhaps a touch like Warhol's religion. He also worked increasingly in physical isolation, starting with a move to Woodstock in 1967. Then, too, if he comes off as a cranky old man, he was well into his fifties when he hit his jack-booted style. Yet lovers and haters can miss, too, how much Guston's breakthrough has in common with his past.

Was his late work all about social issues? Born in 1912 to Jewish immigrants in Montreal, he was old enough to have worked on WPA murals of labor in New York, in the days of Diego Rivera and Mexican murals as well. Or was his late style all black and in your face? So were late drip paintings from Jackson Pollock. A 2003 Guston retrospective at the Met told the story, and I shall not repeat what I saw them (so do read more at the link). Still, with two large rooms in Chelsea, a crucial focus, and some of his best-known work, one can now see what was at stake as never before.

Roughly speaking, the first room tackles the Klan and the second the boots. In the first, he seems ever-present, cigarette between his lips even in bed. In the second, he seems to have vanished, behind black paint and blank walls. That misses out, though, on just how far his mind wanders and how far he is wrapped up in everything—and not just the nation's guilt or his own. The work itself seems trapped within the narrow confines of his studio, just as a country is trapped by his racist history. When a pile of boots looms behind a door barely ajar, it is hard to say which is the greater obstacle to entrances and exits.

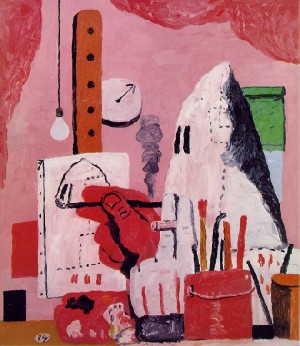

He captures a large, nasty bug on a wall. He captures eyes facing up, teary or lying awake at night. Above all, he captures himself. In a self-portrait at work, he is painting a Klansman while wearing the same hood, painting from life without even need for a mirror. He paints a blackboard with more Klansman, as in a classroom demonstration with himself as the only student. He points a literal finger at still more hooded figures—unless, that is, the hand of god is pointing at him.

A jungle out there

Wilfredo Lam never quite settled in New York, but he found a welcome. He exhibited here in 1939, still in his thirties—when Modernism, a quarter century past the legendary Armory Show, still had the shock of the new. Living in Paris, he mingled with André Breton and Pablo Picasso, who helped him obtain his first show. Critics saw an affinity with Henri Matisse as well. Like Max Ernst, he sought refuge as the war began in the south of France, and Surrealism was another constant of his art. Younger Americans like Pollock delighted in it and struggled with it, too.

A few years later Lam escaped to his birthplace, Cuba, with a trip to Haiti, where he discovered more local traditions and a rawer edge. Critics in New York hailed him as a representative of the "new tendency" in art—the tendency that became Abstract Expressionist. He has often displayed alongside it since The Jungle entered the Museum of Modern Art. Nearly eight feet in height, its gouache on paper seemed of a piece with the movement's all-over painting and mural scale. Not that he had left Picasso behind, and it feels at home at MoMA near the brothel scene of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon as well. Its tall figures, some holding their own masks, could belong to ancient terrors and or urban anxieties in the present.

Which, though, has the greater claim to Lam? He may not have been strictly Eurocentric, but he died in France, gave his work French titles, and never turned his back on Europe. He also had a more complicated ancestry than the labels give out. Born in 1902, he had a Chinese father and a mother with parents from the Congo and Spain. He studied in Spain, leaving him plenty of time to absorb the wonders of the Prado. Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel had their nightmares, too. On a trip to Mexico, he may have had a glimpse of ancient forms, but he stayed with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

Which, though, has the greater claim to Lam? He may not have been strictly Eurocentric, but he died in France, gave his work French titles, and never turned his back on Europe. He also had a more complicated ancestry than the labels give out. Born in 1902, he had a Chinese father and a mother with parents from the Congo and Spain. He studied in Spain, leaving him plenty of time to absorb the wonders of the Prado. Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel had their nightmares, too. On a trip to Mexico, he may have had a glimpse of ancient forms, but he stayed with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

He may elude the textbooks because he also eludes description. Those who want a purer national identity may disdain him—just as they may disdain "the primitive" as cultural imperialism. Still, Lam could never settle for the modern city. Born in a village, he used his time in Spain to look well beyond Madrid and urban sophisticates. Back in Cuba, he identified his imagery with ancient religion. As with The Birth for Pollock, he sought a point of origin within.

Lam can stand for a Surrealism beyond Europe—one that liberates native ideals and native peoples. He would have brought more to a show at the Met of just that than the Abstract Expressionism of Arshile Gorky. By the same token, he can also seem hopelessly old-fashioned, like the Cubism of women artists in "Labyrinth of Forms" at the Whitney. Still, not everything out there is a jungle. He really can look ahead to the Afro-Caribbean diaspora now—like Renée Stout or the Cuban art of Manuel Mendive, Yoan Capote, Juan Francisco Elso, and Belkis Ayón.

The show extends to small sculpture in bronze or ceramic, and it gives special weight to the late 1940s. They mark a shift in his art toward cleaner compositions with fewer figures, between human, spirit, and animal. Each is its own comic or frightening mask, like late Picasso. They are lighter or darker canvases as well, physically and emotionally. Their modulations of gray and black offer a ground for Lam's superb draftsmanship—and an escape from pat notions of identity. Who knows what lies behind the masks?

Philip Guston ran at Hauser & Wirth through October 30, 2021, Wilfredo Lam ran at Pace through December 21, 2021. Related reviews looks at Philip Guston in retrospective and Guston's Klansmen.