The Aura of Popular Art

John Haberin New York City

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawings and Prints

Jacob Lawrence: Over the Line

Can there be a truly popular art? It sounds like an insane question, but it helps suggest the draw—and the staying power—of two very different exhibitions.

At the Met, drawings by Pieter Bruegel hang next to the prints for which he drew. Nearby hung stylists in demand in their time, men who shared much of Bruegel's outlook but without so much as a name in the history books today. At the Whitney, Jacob Lawrence paints for himself, for the black community, for white America—and for a children's book, too. Their ability to reach out to a mass medium, as well as what gets lost along the way, says more than a little about the changing nature of popular art.

Detachment and sympathy

The question does sound silly, especially right now. Not even terrorism keeps people from lining up to see Vincent van Gogh. New York galleries have turned into tourist attractions. Where once workers fought to remove Tilted Arc from their lunch space, massive rusted steel from Richard Serra now turns a gallery into a playground for Switch. Besides, no one is forgetting modernity's ultimate popular art, movies.

Only the status of art remains as confusing as ever. Long after the supposed death of the avant-garde, few can name a living artist, except from time to time to denounce one. Public arts funding takes its lumps and declines. The hero of the war against terrorism, New York's mayor, has led the denunciations. If all that seems to resurrect the division between an art world and the public, Norman Rockwell's long-awaited retrospective seems pretty much to have disappointed both sides.

Maybe it helps to go back to the beginning. When was art popular, and how? Start with a superb show, largely of drawings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

The artist came at the very end of the Northern Renaissance, after the Antwerp Mannerists and Jan Gossart and as perhaps a student of Pieter Coecke van Aelst, and he drew on a real master of folk imagery and medieval monsters, Hieronymus Bosch. Like the older artist, he depicts fools and scoundrels more than saints and saviors. His early paintings teem with anecdotes, often drawn from the Bible and popular sayings, but often as much for their own sake as for the elliptic message.

Like Bosch, too, he adopted alla prima, a quick, flat application of color areas more like another kind of folk art, Americana, than Jan van Eyck and his subtly layered glazes. He might set this against more brilliant color and chiaroscuro, to bring out the simplicity of men and women in a rich, ever-strange world. Later in life he begins to concentrate with new respect, up close, on a few peasant forms, as for Bruegel in his Harvesters or Wedding Dance. They carry out their tasks in earthy scenes conceived with a rare depth and naturalness.

Throughout, this new sympathy for humanity takes what might even seem its opposite—an equally revolutionary detachment. Bruegel describes instead of moralizing. Forget Rockwell. Bruegel works for mass reproduction but never quite gives in to its very premise.

The long view

That objectivity and sensitivity enters fully into his drawings at the Met. Instead of following the outline of things, his short, curvy pen strokes create shimmering textures, almost with the rigor of Pointillism. Other artists on display describe mountain chains with a specificity akin to geology. Bruegel stands above the land and looks past it. One may associate single-point perspective with individualism, but for Bruegel it brings a point of view more like a god's.

The prints made after him look stiff and foolish by comparison. They illustrate proverbs, with good and evil as clear as a northern winter's night and day. Turning to the original drawing, one feels something near to shock at the sympathetic attention to the misdeeds.

Bruegel is a Mannerist, part of the century's turn against, revival of, and quotation of High Renaissance ideals. One sees it in his refusal of heroes. One sees it in his great diagonals rather than the formal pyramids of the generation before. Yet art history takes its terms from an age-old privilege accorded Italy. One thinks of Mannerism as distortion, a pessimistic turn against High Renaissance hierarchies of experience. Mannerists, one imagines, pull the eye away from any central subject—whether in a spirit of hope and perplexity, as for late Raphael, of shy retreat, as for Parmigianino in late portraits like Antea, or of sheer despair, as for Pontormo.

Oddly enough, up north it is Bosch—or Mathis Grünewald, another master of agony and death—who aspires to High Renaissance grandeur and its centralized compositions. To Bruegel, a change in style came with a growing acceptance of eternity and change. No wonder his finest series, late in his career, depicts the seasons. Quite literally, this artist takes the long view. In his long diagonals and soft earth tones, one sees the Baroque, including the great Flemish and Dutch landscapes soon to come.

One sees also a changing attitude to the workshop. Bruegel makes it hard, even with all his known skill, to be sure how much he completed, even when he experimented with the Renaissance etching. He keeps his influence by becoming a kind of factory. In the same way, the prints spread his name without undermining all that they lose, in his unique hand and ability to forge an image that people will remember.

With its usual pedantic overkill, the Met not only uses labels to add platitudes of its own to every drawing. It also, for some reason, feels compelled to supply the print after every saying. Surely just a few examples would do. Still, at least it demonstrates how mass reproduction helps shape the irreproducible reputation of a great popular artist.

Poster child

Contrary to some postmodern complaints, the division between high and low goes back centuries, and Modernism did more than anything to break it up. As art filled churches, clumsier icons and woodcuts entered homes—but from artists often unknown today. With the growth of a merchant class, individuals commissioned the top artists around, but that only solidified divisions in status, whether among artists or within a single workshop.

For there to be popular art, there has to be a popular market, and artists have to have the practical means to reach it. They also have to have a way to maintain their cachet. They have to create themselves and their images as a kind of trademark. That takes a sophisticated technology of reproduction. The great artist is a poster child. Perhaps, I should add, a poster child of silence and slow time.

Critics from Walter Benjamin to Rosalind E. Krauss have looked to mass reproduction to dispel the "aura" of fine art and the "originality of the avant-garde." If today's art-world stars are any indication, it has not happened. And the reason should be clear. As for Bruegel, originality and reproduction go hand in hand. Reproduction at once disseminates an image and attests to all that has gotten lost along the way. Besides, prints can beg for authenticity, too.

Conversely, the avant-garde undermined art's aura all along. Instead of copying after the masters and reproduction, it played with past art and its own image. It developed works that can make sense only in another kind of repetition, geometric and narrative series. It makes possible art at once popular in its own right and distinctively personal, an art that falls between or outright dismantles distinctions of high and low. Think of movies, meant to appear over and over but with the mark of a director. Or take the case of Jacob Lawrence.

"High" art had eaten into the old ideal of authenticity with repetition, citation, and the power of words. "Low" art had long accepted its status in reproduction. Lawrence knows both, and it creates a Modernism that aspires beyond the museum and its white, privileged audience. That balancing act may never work for long, but it rewarded him with instant success.

As a fine retrospective makes clear, at his best he commands movement, repetition, and silhouette within a single frame. One of his hardest to make out at first glance, a shooting gallery, is dazzling. One shares in the tawdry pleasure. Because flatness can stand for a person as well as a target, one gets lost figuring out who is shooting whom. But his real success comes with series of works that tell a story. At the Whitney, one sees his stories emerge with remarkable freshness.

Words and deeds

Appropriately enough, Lawrence's mix of high and low has its roots in a tamer, all-too-earnest Modernism, a uniquely American art. Not for him the formalism or expressionism of an avant-garde. As for Stuart Davis as perhaps the very first Pop artist, Cubism had to translate into the jagged rhythms of a city street. As for Charles Burchfield, the bold curves of Henri Matisse made sense only as the sweeping violence of men and nature. Whatever the title of Lawrence's retrospective may say, this art did not go readily "over the line."

An annoying cliché blames modern art on one notable kind of reproduction, photography. Once cameras can handle reality, painters had to move on. Painters never did move on, however, and Lawrence suggests why. Photography and European art alike, he suggests, turn on familiar subjects, abrupt endings, and darkened silhouettes. His early canvases cut things off almost at random.

The frame becomes a part of the picture, just as the pedestal enters sculpture by Brancusi or Giacometti. If that brings a viewer into the picture, too, decades before Minimalism, that is the idea. Lawrence's rough street life itself calls on people, both blacks and whites, to start taking responsibility. His art appeals not to a universal esthetics, but to the conscience of a community. Less happily, the cutoffs also mean some pretty loose compositions. Responsibility always comes with the demand to remember, but those early paintings, alas, will never stick in my mind.

The frame becomes a part of the picture, just as the pedestal enters sculpture by Brancusi or Giacometti. If that brings a viewer into the picture, too, decades before Minimalism, that is the idea. Lawrence's rough street life itself calls on people, both blacks and whites, to start taking responsibility. His art appeals not to a universal esthetics, but to the conscience of a community. Less happily, the cutoffs also mean some pretty loose compositions. Responsibility always comes with the demand to remember, but those early paintings, alas, will never stick in my mind.

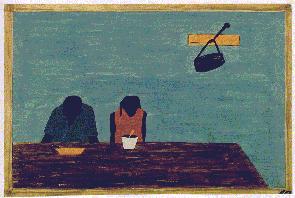

Ironically, Lawrence's success as a populist comes with an increasing formalism. As he learns to tame those sharp edges, he also learns an art of repetition and simplicity. The Migration Series, his greatest triumph, draws power from the lone victim of a lynching. It echoes the bitter procession to a train north or the tenement windows of a cold, new city. The bright earth colors adapt to fields in the heat, bare walls, and the aspirations of human flesh. They raise questions about fine art and humanity just as they did a few years ago, when I encountered the Modern's separate exhibition of the series.

Lawrence has discovered his twin signature, the silhouette and the series. With the first, he finds a stark majesty, just as Giotto had centuries ago when he placed a figure with its back to the viewer. A silhouette also recalls a truly popular art, another art of reproductions: the cutout suggests something primitive and accessible, like old woodcuts or the alla prima faces of Bosch and Bruegel. From lithographs to magazines, from van Gogh to Pop Art, this century messes up the rankings.

A series has the same dual appeal. Like a proper formalist, from Mondrian to LeWitt, it repeats the vertical. Yet it also means that no one work has final say, that every painting cites another, and above all, they tell a story. For Lawrence, too, titles function not just as identifiers, but also as captions. Like his frames, words enter into these works, and they did so long before Postmodernism came up with the idea.

Masks in black and white

The Migration Series made him a star in Harlem and the art world. Two major museums split up the series, one taking the odds and one the evens. The isolation of an individual canvas almost destroys the whole idea. It asks one to see each work apart from others and apart from its story. Like the museum purchases, it elevated him firmly to fine art. But then, the fragile place of the series between high and low only adds to its bittersweet edge.

Lawrence will never have the same edge again. As a painter in Harlem, he no longer has the same access to a popular audience or to the modernist mainstream. Back in Depression-era New York, he has his most creative burst ever, but no single canvases can ever quite tell the same story. Still, that shooting gallery points to a key new element in his art. Gaming has given fresh meaning to that trademark silhouette.

Lawrence returns often to masks and puppets, with all their implications for a black artist in white America. They hold the vitality of the street, but powerlessness and empty façades, too. Unfortunately, they also sometimes hide the horrible toll of racism, reducing the gamble of The Migration Series to a puppet show. Lawrence sticks to storytelling, but his stories increasingly have happy endings. When he returns to series, their popular message sounds repetitive.

Lawrence makes that return with World War II. The government invited him to join the war effort in order to paint it. From now on, he largely sticks to series, and he never again allows himself a mixed message. Sure, war is hell, and Truman had not yet integrated the military. He shows all that, but he cannot let it take over. War rallied America, and the good guys won. And they did it by hanging on.

Lawrence keeps looking for narratives of endurance. For a children's book, he chooses the life of Harriet Tubman. He then takes time off in Africa to rediscover his spiritual bearings. Both these stories have a simple direction, and it strips his love of repetition of its very vitality. Tubman takes slaves north, and then she comes back to take some more. The dense groupings and taut isolation, sweeping lines and intense earth colors—all vanish, along with ambivalence and tension.

Yet these stories reached people, and they do today. His retrospective has the power to get visitors talking. Forgotten by art history, limited in his reach, Lawrence fell after one great moment between high and low. In a long career of small successes, it may well make him the quintessential popular artist after all. Like his masks and puppets, he could stand for the dreams of Modernism itself.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder's drawings and prints ran through December 2, 2001, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jacob Lawrence ran through February 3, 2002, at The Whitney Museum of American Art. Related reviews look at Bruegel's Wedding Dance, Lawrence's "Migration Series," and his "American Struggle."