Claiming Succession

John Haberin New York City

Steffani Jemison, (Never) as I Was, and Joseph E. Yoakum

Meaning in art has taken quite a beating. Can an artist dream of reclaiming it for herself? Can her subjects? Now imagine that the artist is a black woman. The question just got a lot more urgent.

Steffani Jemison had her opening just two days after the unlikely specter of "critical race theory" helped throw the election for governor of Virginia, but she does not need that or any other critical theory to ask. The very idea of inheritance or possession goes into the title of one video, In Succession. It runs implicitly through this year's Studio Museum artists in residence as well, in "(Never) as I Was," with an assist from MoMA PS1. They just do an awkward job of expressing it. As for meaning, ever stop to wonder what you might do with the rest of your life? Joseph E. Yoakum was in a retirement home in Chicago in 1962, when the answer came to him in a dream.

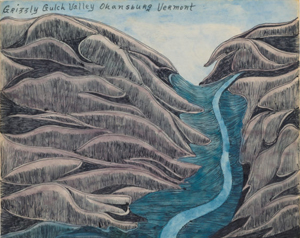

It told the African American that he could travel the world—cheaply and comfortably at that, even for a man of seventy-one. He had his memories to guide him, real or imagined. He had his colored pencils and ballpoint pens to carry him, for he would travel through art alone. "Wherever my mind led me, I would go," he said. "I've been all over this world four times." The world for him seems in perpetual motion itself, at the Museum of Modern Art.

The communal experiment

The video is Steffani Jemison at her most modest, most open, most enigmatic, and most persistent. Lush but murky surfaces slip across its split screen in black and white, all the richer and harder to follow as one half cuts off the other. They appear to be clothing or flesh—African American clothing or African American flesh. If it is a tour de force, she merely documents one, as six men form a human pyramid, relying on her and each other for their different kinds of support. She cannot, though, point to a single story. There are too many, filtered through mainstream media all too ready to cast African Americans as heroes or, more often, villains.

In one, as long ago as 1931, men formed a pyramid to reach a higher floor, to rescue a woman trapped in a fire. They could have claimed credit, but instead they merely slipped away. In another, a pyramid served in a jailbreak, and they had every reason not to stick around. Jemison can mention other stories, too, but then who is counting? She does not object to looking back to white artists either, doing no more than recreating their act. If its significance has changed, you will understand.

Back in 1971, Bas Jan Ader filmed a man holding onto a tree branch with both hands for as long as he could, as Broken Fall (Organic). It was not long, and it was not long either for Jemison's callow young man in 2008, in a video of the same name. He seems unable to manage a single pull-up much less a display of black masculinity before falling out of the picture, and there is no telling what might break his fall. The kids in Escaped Lunatic from 2011 are more eager to slip out of the picture. Dressed in the same white shirt and casual pants, they run as fast as they can through a suburban or industrial wasteland. Someone may or may not be hot on their tail.

Was your first thought to fear for them or to call the police? If the latter, you have something in common with the sole actor in The Meaning of Various Photographs to Ed Henderson. John Baldessari, about as literal an artist as they come, pulled news photos for examination in 1973, when Postmodern was just getting going and at its most skeptical. Unlike the "Pictures generation" and Sarah Charlesworth, Baldessari did not have a political agenda, but his subject was happy to supply one, at least for that photo. In one last video, from 2010, Henderson has become Tyrand Needham, and the photos have become more sexually charged, but then times change. If Jemison is right, they can still change, but only so fast and so far.

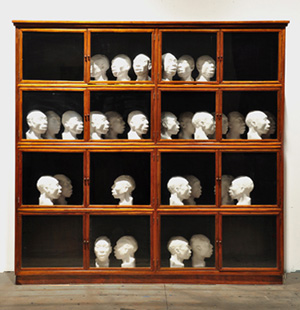

Radcliffe Bailey, too, embraces multiple time frames and the shallow, uncertain space of the picture plane. He has also kept up his pursuit of the slave trade, and I can only ask you to check out a past review for more. His collage behind glass, in black and blood red, looks only more impressive after ten years. It could be a light box with its only illumination from paint, or a cabinet for historic maps. His white plaster heads now rest on curved wood, like the underside of a slave ship, but he is perfectly ready to engage Western art as a good so long as it accommodates African American tradition. The top of a stringed instrument ends in a totem.

Neither artist is closed to thoughts of a black utopia. A text painting by Jemison approximates a book of that name, subtitled The Negro Communal Experiment in America. Alas, the experiment is now nearly sixty years old, and the cover has had plenty of time, judging by the painting, to acquire stains. Its title is also close to unreadable, but do not give up yet. Unlike text art by Glenn Ligon or Adam Pendleton, she is not gloating, and she is as ready to embrace monochrome abstraction as Postmodernism or new media. An exhibition is almost by definition a communal experiment. This experiment just happens also to involve you.

Virtual residence

At last, MoMA PS1 has solved the homeless crisis. People on the street will all have virtual housing, although it may not provide much in the way of shelter. So what if it leaves them to fend for themselves—like this year's Studio Museum artists in residence without a museum studio or residence? Creating affordable housing or studio spaces is expensive. (I hope the artists at least got a stipend.) Isolation can take its toll, though, and the results are decidedly self-involved.

The Studio Museum in Harlem has always been a step ahead of the game, so why not ahead of a pandemic as well? It closed its doors before the lockdown for renovation and expansion, and its artists in residence had to reside elsewhere. They have exhibited instead thanks to MoMA, and they do so again for a third year—only this time with a difference: they must find a place to work on their own. Instead of a "virtual exhibition," they get physical proof of a virtual residency, as "(Never) as I Was." It permits an expanded program, with four rather than three artists, but at a cost.

Will life or art after Covid-19 be ever again as it was? If the question sounds premature or just plain pretentious, the show runs that risk as well. Pride and pretension often come with the drive to highlight diversity, and the artists boast of their inheritance. Residency aside, though, they also speak of home. Genesis Jerez evokes it in charcoal and oil, based on family photos. Yet she speaks of "diasporic fracture" as well, and the life inside seems hauntingly dead and gone.

Her technique lends precision and immediacy, but also an unbridgeable distance. Old fabric can become a new tabletop, but in black and white. Fruit on the table can add accents of color, but all the flatter for that. Still life has a traditional association with mortality, as in the golden age of Dutch painting and Dutch drawings, but fruit for Jerez is never rotting or luscious. It is a lament for all that she imagined or knew. Text within her collage quotes Psalm 59, with its plea to "deliver me" with a "clean heart" and a "right spirit," but deliverance may have come all too soon.

Elsewhere, questions of identity win out over guilt, and so does pretension. Born in Haiti, Widline Cadet makes the Afro-Caribbean diaspora explicit, but in photos that elevate friends her own age into idols. Small monitors built into two works barely break the complacency, as do transparencies perched uneasily in corners of the room. As for icons, Texas Isaiah goes all the way, with "transmasculine altars" to gender and the dead. He preserves a rose, a stone or two, votive candles, and photographs along with a victim's favorite books, LPs, booze, and t-shirts. Deliver me, please.

Over the years, the Studio Museum series has brought attention to such artists as Leslie Hewitt, Jordan Casteel, and Michael Queenland. It is a shame to see it so complacent. When Jacolby Satterwhite takes up painting after past shows of emerging artists and the heritage of Romare Bearden, the Great Migration, and civil rights, he settles for African Americans just hanging out. On video, though, he lets loose, at the borders of a lake or in an impossible interior—a lecture hall but with clay models and skeletons for lecturers, monitors for students, and a pulsing soundtrack. Text offers more pat moral lessons about hurting others and hell, but never mind. Hell here is other people and the place to be.

Moving mountains

Those memories for Joseph E. Yoakum go way back, and they echo the America dream. He claimed to have run away from home to join a circus, as a personal assistant to John Ringling of Ringling Bros. as they crossed the United States. He claimed to have worked for Buffalo Bill before that, and sure enough one drawing depicts Bill's home, while others look to the great outdoors from Alaska to Vermont. He claimed also to have seen the Middle East, Russia, and more. His titles identify each and every scene, with increasing length and specificity. From all appearances, though, he could not get past a single mountain.

He had a healthy precedent for just that, in Paul Cézanne and Cézanne drawings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, although he might well have denied so much as knowing the name. He had all of Cézanne's obsession, but none of Cézanne's faith in observation and the art of museums. He styled himself a self-taught artist, and his free-flowing line has all the madness of outsider art. So do the stories he told and the identities that he claimed. He called himself a Native American, a "Nava-Joe" (as in Joseph), although others saw him as black. He served in a segregated regiment in World War I, one that never saw combat, and the south side of Chicago was more than segregated enough in 1962.

He had a healthy precedent for just that, in Paul Cézanne and Cézanne drawings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, although he might well have denied so much as knowing the name. He had all of Cézanne's obsession, but none of Cézanne's faith in observation and the art of museums. He styled himself a self-taught artist, and his free-flowing line has all the madness of outsider art. So do the stories he told and the identities that he claimed. He called himself a Native American, a "Nava-Joe" (as in Joseph), although others saw him as black. He served in a segregated regiment in World War I, one that never saw combat, and the south side of Chicago was more than segregated enough in 1962.

In reality, he was born not on an Arizona reservation but in Missouri, where his father was a railway worker. He may even have had some arts education, if not like Jaune Quick-to-See Smith decades later. As curators, Esther Adler, Mark Pascale of the Art Institute of Chicago, and Edouard Kopp of the Menil Drawing Institute make only modest efforts to pin him down, and one can see why: the stories are just too good to lose. When a train in a drawing crosses the mountains, they mention Yoakum's childhood memories of train travel, which may well be true. But then rivers, pockets of greenery, and sailing ships weave through his landscapes, too.

The mountains themselves might be in motion and alive, their peaks like rising or falling leaves. Redoubled curves add to their intensity, while pastel and watercolor add their touches as well. A rocky outcrop off-shore in Hawaii could be a temptress or a sea monster. Yoakum has his limits as a colorist, but color grows in intensity for the repeated motifs of rainbows and a rising sun. He is drawn to place names like Rainbow Canyon and Mount Calvary, too. He called the Bible his favorite storybook.

For all that, his landscapes have little room for parables. People might be superfluous, and fables from a practicing Christian Scientist would be as unreliable as everything else he touched if they did appear. The more than a hundred drawings have no obvious progression. None are dated, and all date to that one decade before his death in 1972. They might belong to a single unfolding story of natural growth and geologic time. The artist has his perpetually shifting identities as well.

He has surprising strengths as a draftsman—and that, too, points to the puzzle of ancestry and identity. Yoakum sketches a Breck girl and Nat King Cole, skillfully but hardly from life. He sketches tribal leaders with no obvious model. The title of one drawing begins "What I Saw," and MoMA adopts it at face value for the show itself. Make fun of it all you like. The imagination can move mountains.

Steffani Jemison ran at Greene Naftali through December 4, 2021, Radcliffe Bailey at Jack Shainman through December 18. "(Never) as I Was" ran at MoMA PS1 through January 27, 2022, in conjunction with the Studio Museum in Harlem, Joseph E. Yoakum at The Museum of Modern Art through March 19.