Circuitry and Sprawl

John Haberin New York City

James Hoff and Jane Freilicher

Amy Bennett and Landscape

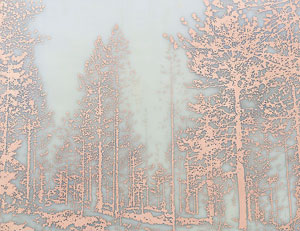

Even in December, the trees on Delancey Street have a coppery glow. It is the glow of landscape painting, but not by traditional means. James Hoff evokes not just the glories of autumn, but the metallic tones of electronic circuits—and the devices that litter the land.

Hoff is painting all the same, in tribute to the landscape. He objects to human habits that spoil it. In contrast, Jane Freilicher celebrates those habits, with feathery brushwork out of the New York School and the view from her West Village studio. Together, they also highlight the diversity of art and its resources. Painting and photography, in turn, carry on tradition while wondering at humanity's distance from the earth. Amy Bennett, for one, takes her oil painting out of doors, but she is still living with suburban sprawl.

Autumn on Delancey Street

No, that copper is not the glow of fall foliage, not on a Lower East Side thoroughfare better known for traffic than for signs of life. At least one gallery has bricked up its glass façade to keep out the sights and sounds. No, these trees exist only within a work of art, and this copper is the real thing—the transition metal, the twenty-ninth element in the periodic table. James Hoff etches it on fiberglass, for the silhouettes of trees. It outlines trunks, leaves, and branches with a delicacy and density that would defy many a landscape artist. Then again, Hoff borrows the technique used to create microelectronics.

He brings more of nature into the gallery as well, so that it, too, takes on the appearance of a landscape. Mottled stones lie here and there on the floor. They look natural enough that visitors may already expect some trickery. Perhaps he cast them in foam, for the mere illusion of stone. Yet once again they are the real thing, only this time the reality of the found object, give or take a little help. He has painted them black and white.

They promise an enclave apart from the city, but beware. Hoff calls the show "Utopia Landfill, or Vacation in the Age of Sad Passion"—and it does not sound like a recommendation of where to escape the coming winter. Of course, others, too, have wondered where the inorganic ends and where life begins. Garret Kane, for one, has embedded electronic circuits into carvings that evoke schools of fish. This artist, though, is not in awe of the digital. When he looks forward, like Sophia Al-Maria at the Whitney, he sees toxic waste from used devices and a cramped imagination. He makes a point of having started with photos of the great outdoors from a cell phone.

Hoff's ambivalence toward humanity and nature also extends to art. He begins like Paul Paiement with the conventions of landscape painting, and he compares the technique of etching circuitry to screen prints. Copper has its place in art history as well, as an alloy with tin. Sculpture in bronze all but invented the Renaissance—with The Gates of Paradise, the doors to the Baptistry in Florence by Lorenzo Ghiberti. Hoff also models his black and white stones after camouflage, and he notes that artists created those patterns in World War I. He does not mean it as a compliment.

Maybe, though, he should—or maybe he understates how much he already does. Maybe he knows that, all along, living creatures have depended on copper to carry oxygen, much like iron in humans. Maybe he knows, too, just how much he, like Lois Dodd, evokes a tradition of landscape painting. Even as Useless Landscape, the tracery on fiberglass glows with autumn, and the stones carry it into a third dimension. Art always thrives on the border between nature and culture. Now it just takes on appropriation and the digital.

Pamela Rosenkranz loves the landscape and, for that matter, the chemicals that shape its experience. She calls her show "Anemine"#8212;and, just, for the record, that means a green substance distilled from annelids, or worms, that covers the Amazon. And here you thought that Frederic Edwin Church knew the rain forest. In practice, one can set aside biochemistry for a study in blue and green. In unfolds on fluorescent lights, taking up the gallery's usual track lighting. It extends to smeared acrylic on aluminum and to sound enveloping them all. It feels like James Turrell descending to industrial lighting or Dan Flavin reaching for the sublime, but it presents both a natural and interior light.

Improvising New York

Jane Freilicher brought a lyricism to the New York School. It made her hard to hear amid the clamor of the 1950s, but it had room for dark sunsets and the city's explosive growth. Like her friend Larry Rivers, Lee Krasner, and others in the movement, she studied with Hans Hofmann. Like Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, she split her time between Manhattan and Long Island, taking both as her subject. Like Fairfield Porter, she also kept representation alive, though without the crisp light that brings Porter closer to abstraction and that influences Eleanor Ray today. Together with Daniel Heidkamp and Mira Dancy, she seems newly a part of the city.

When one speaks of Abstract Expressionism as the New York School, one can forget that the term also refers to poets like John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, and Frank O'Hara, with a rough and ready cadence akin to jazz. Freilicher counted them, too, as friends, and she called a view from her studio Improvisation. It suggests the immediacy of skyscrapers and water towers pressing in. It suggests, too, her brushwork on raw linen. Red red sinks into blue and light into shadow, in paintings from three decades. Yet it also suggests a musician's making it up as she goes, and she had no qualms about adjusting what she saw.

Neither does Heidkamp, who updates Freilicher for today's real estate values. His view from a midtown hotel room includes iconic buildings in all the wrong places. A fisheye window draws them together in the darkness. The Empire State Building spire bends like the wick of a candle, with a spot of red like flame. He is settling in for the night, in a place that few emerging artists could afford. If he is imagining any or all of it, he calls it Dreams.

He, too, paints his studio, but not looking out. It has landscapes on the wall—and enough floor space for a boom box, work gloves that fail to meet in a handshake, and a worktable that looks suspiciously like a grill. The studio, it seems to say, is his backyard. As Pink Room, it also evokes Henri Matisse with a touch of kitsch. Pink may imply gender bending, and another night sky includes a billboard for Call Kelley. The High Line hurtles past with the breadth and pace of an expressway.

Dancy is more claustrophobic and closer to Matisse as well. Her studio views look within, with titles like Psychic Fall Out. Irregular shapes form a dense tapestry, in bright primary colors. One painting has a twisted stop sign. It serves as a warning less to passing traffic than to the viewer or her. She needs it.

Have they come a long way from Freilicher? She could still afford the West Village, and her studio ledge held houseplants, not warnings or advertising. She could not, like Heidkamp, spot a sculpture by Mike Kelley through a distant window. She would have hated it at that. Still, she belongs more than ever to the night. She died in 2014, at age eighty.

A long way from home

Amy Bennett has ventured out of doors. She might have been there all along, starting in 2003 when she painted houses from above, as if from her own private satellite. She saw right through the roof, though, or simply tore it away, for her focus lay within. Ever since, she has brought to her small interiors the unrelenting eye of a spy cam, with all its claims to objectivity—and all its investment in other peoples' lives. Everything spoke to them,  from the broken window to the couple never quite sharing a breakfast, and everything eluded her, in unstated narratives and empty rooms. She was, after all, looking in from outside.

from the broken window to the couple never quite sharing a breakfast, and everything eluded her, in unstated narratives and empty rooms. She was, after all, looking in from outside.

Now she is looking around her, almost ready to call it home. She has moved up the Hudson and started a family, and her latest paintings sweep across landscapes, both suburban and rural. Other artists, too, have created otherworldly dioramas of this world. They have imagined dollhouses as communities, like Susan Leopold and Beverly Buchanan, or communities as an alien form of life, like Gregory Crewdson and Jeff Wall. Bennett still, though, keeps an unsettling distance, with the view from above. She still has a fascination with what she cannot see as well.

She keeps looking all the same. As ever, these are virtuoso performances, sharing the gallery with equally panoramic abstractions by Iva Gueorguieva. As before, walls take on light and mass, even as the predominant blues and greens seem out of a dream. The course of shadow keeps things in motion, much like the clutter of ponds, farms, and houses. Leaving the city and floor plans means setting aside the grid. It also means roads, churches, and shopping malls without a sense of shared spaces—and with no people in sight.

Bennett earns her distance by her working methods. She has painted interiors before with the aid of a model in her studio. Now she begins by with a larger construction in Styrofoam that one can picture but never see. She also finds inspiration in Google maps, much like Daniel Hesidence in abstraction. She leaves unstated which community is hers. She may have invented them all, but they could almost add up to a single landscape that one could call home.

Vanessa Marsh, too, seems poised between villages and the great outdoors. She even calls her show "Everything All at Once." Not that much is happening, in contrast to piled flatcars and factories in acrylic fantasies by Amy Casey in the front room. Marsh's real and artificial landscapes have no people either, just their traces. They appear in the silhouettes of utility poles, clotheslines, a billboard, and even a roller coaster. They must have planted those picturesque trees.

Still, somehow light pollution has not effaced the stars. Which is more real, humanity or nature? Humanity looms larger and closer to the picture plane, in what are actually photograms touched by drawing. The many points of light do not bother to assemble into constellations. Both might have pressed directly up against the photographic plate. And neither touches the ground.

James Hoff ran at Callicoon through December 23, 2016, Pamela Rosenkranz at Miguel Abreu through December 22, Amy Bennett and Iva Gueorguieva at Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe through October 8, and Vanessa Marsh and Amy Casey at Foley through October 30. Jane Freilicher, Daniel Heidkamp, and Mira Dancy ran at Derek Eller through February 5, 2017. The review of Hoff first appeared in a slightly different form in Artillery magazine. Related reviews have looked at biology and electronics, sprawltown, and interiors by Amy Bennett.